How Patience Pays Off

This essay could be a long-winded way of saying “good things come to those who wait.” But the saying isn’t foolproof – waiting can easily lead to decay.

The difference is between active patience and passive patience, and we believe it’s active patience that pays off. Pulling back an arrow and holding that tension may not look like much in the moment, but you’re creating the circumstances for a powerful event to take place. Similarly, active patience is about moving (and not moving) with intention, consistently weighing resources and opportunity costs, and recognizing the compounding rewards of high trust and persistence so that you’re best positioned to act on an opportunity when it presents itself.

Most people, including us, are not naturally inclined to wait, to be content building energy and potential. In fact, “progress anxiety” is a term regularly used around the office. We balk at the idea of passive, unproductive, non-strategic waiting and also believe that “good things take time.” The quality of restraint is downstream from purpose.

The long game requires a plan. It demands clear vision, helpful structure, and healthy incentives that promote active patience and curb tendencies towards frenetic action, short feedback loops, and quick wins (over sustainable ones) in the name of showing progress.

Patience is a choice, and it’s one that must be made continuously and rigorously, through long-term commitment and persistent discipline. Put another way, it’s hard and we’re still learning.

What It Takes

“Patience is waiting. Not passively waiting. That is laziness. But to keep going when the going is hard and slow – that is patience. The two most powerful warriors are patience and time.”

Patience requires determination. Exercising patience without losing confidence, humility, or sense of self is hard enough, but you will also need perseverance and diligence. Mary Oliver calls it the “patience of vegetables and saints.” Others call it “grit” – that determination and commitment that drive us to long-term goals without the guarantee of short-term payoffs. Small business owners know grit. They’re the definition of durability, establishing deep roots in their communities, building companies with strong foundations, bringing consistent excellence to what they do best, and grinding toward a vision that may not materialize for decades or generations. This is patience at work, through work.

Patience requires the ability to be patient. If you don’t have the financial, mental, or emotional discipline to withstand a decline or a period of extreme underperformance, you don’t have the ability to be patient. The flip side of that coin is that you can’t lose your mind during periods of success. Also, most people lose their minds during periods of success. Patience can be interrupted by failure and uncertainty, of course, but short-term success can be even more threatening to patience, especially since luck is always involved. Success breeds confidence, which creeps into overconfidence, which leads to arrogance, which divorces you from reality, which cometh before the fall – failing in obvious, foreseeable, and avoidable ways.

Patience requires a team. But no founder is an island. Patience requires not only personal fortitude, but a team that will ride out the storm and continue to row with you. Conviction isn’t enough, and individual grit quickly devolves into stubbornness. If your significant other, investors, colleagues, employees, kids, and friends won’t go for the ride, you’re not going either. Or, you choose a life of isolation. So patience in some ways requires persuasion.

For what it’s worth (and we think it’s worth a great deal), the practice of patience also helps do this persuasive work. It’s informal, but a recent survey indicated that leaders committed to showing patience ramped up employees’ creativity and collaboration by 16% and their productivity by 13%. Patience is infectious. Patience begets patience, which gives everyone time to align collective postures.

Patience requires openness. However, extreme commitment to patience can come back to bite you. Smart owners, operators, and investors know the perils of doggedly following the original strategy over figuring out what it takes to survive. Patience can be confused with stubbornness or pride. No one wants to look wishy-washy or fickle. But surviving (and, eventually, thriving) requires an open posture. Bayesian updating is a cornerstone of patience. There’s always a gap between the stories we tell ourselves and reality. The smaller the gap, the better our judgment, and the more likely we can be appropriately patient.

Patience requires trust – trust the science, trust the system, trust your gut, or, if you’re the Philadelphia 76ers, trust the process. Patience is waiting in light of a desire and pressure to act. When faced with a problem, in order to not act you must trust that something better is coming. But that trust isn’t naive, nor is it idle. We might tweak the old “trust, but verify” in this case to “trust, but work.”

Finally, patience requires gratitude, compassion, and humility. These qualities combat selfish desires to profit at the expense of others. It’s hard to act out when you’re self-aware and at peace. And that, in turn, promotes patience, reinvestment, perseverance, and an overall preference for future rewards of compounding value. In this case, humility means knowing what you bring to the table and the value of investing in the future. If you’ve assessed yourself with candor and fearlessness, you have already begun to cultivate resilience and patience.

Patience is demanding. It requires these qualities and commitments because it only works if you work it again and again.

Why It’s Hard

“Well, we must wait for the future to show.”

Not to be flippant, but patience is hard because it’s hard. Even when you know the reward is going to be bigger in the end, delayed gratification feels like a loss. And, we all hate to lose.

Behavioral decision-making research suggests we have complex (and frustrating) natural processing around future consequences of decisions in the context of opportunity cost, uncertainty, resource slack, and present bias. In fact there’s a name for our impatience, and a price tag we’re willing to pay for it. Fixed-cost present bias indicates that we want to have good things right away, and that we’re willing to pay $4 for it, whatever the size of the outcome under consideration. Losses work the same way – we’d prefer to have them over with and settled sooner rather than later, even if that costs us more. If life and work are a series of present value/future value trade-offs, most of us pick the present most of the time. This present bias is fueled by feelings of deprivation from expected gains and anxiety about looming losses. (There’s nuance around magnitude; people will wait longer for large gains and happily put off bigger losses.)

In short, our brains are hard-wired, and frequently incentivized, to favor the present and the short term. Present bias affects our perception of and willingness to act on losses and gains. It requires a huge effort to continually combat this bias, even when rewards are evident. Case in point: an analysis from Bain Capital revealed that returns from a 24-year holding period on a theoretical deal were almost double those of a series of standard re-underwrites from the same period. And yet short hold periods reign.

The problem is that in private equity, incentives are frequently structured to value short-term gains, including trying to game volatility, utilizing leveraged buyouts, participating in asset-stripping, juicing EBITDA, slashing personnel, buying questionable bolt-ons, and so on. These incentives become the proverbial trees that make the forest invisible and foster a system based on short-term extractions that undercut relationships, long-term growth, and legacies.

Patience requires endurance against obstacles, both known and unanticipated. The longer your time horizon, the more disasters you’ll experience. Most people don't bear hardship well and quit. Depending on luck, periods of extreme hardship and under-performance may come before any success, leading to an expectation of failure. And even if you’ve experienced a bit of success, or even a lot of success, the naysayers will always come out against you. See the many, many hit pieces on Warren Buffett at various stages of his career. The man has been “washed up” more times than a three-year-old’s t-shirt.

We think that a bias towards action (not action in itself – we all must act eventually – but prioritizing action above all else) is inherently prideful; it assumes superior knowledge, perspective, position, and predictability. However, patience is hard, and most people won’t do hard, so it's therefore differentiated and potentially extremely profitable.

What’s the Tradeoff?

“I’m inclined to reserve all judgments, a habit that has opened up many curious natures to me and also made me the victim of not a few veteran bores.”

Commitment, patience, and a focus on the long-term all have opportunity costs. By definition, if you’re tending to things that matter, you’ve identified things that don’t.

Shorter time horizons in private equity are a popular storyline. There are valid reasons for this: deadlines can promote progress, some research suggests constraints (including time pressure) promote invention and creativity, investors want market feedback on returns, etc. Engaging in rapid and authoritative changes can feel good, allow you to take advantage of short-term gains, and leverage liquidity to show results fast. For all the recent talk about “patient capital,” the median private equity hold buyout period in 2021 was 4.4 years, down from 5.8 in 2014. Clearly there’s value to be had – people always behave rationally, but what counts as rational rests on your priorities.

The problem with patience is that it’s frequently invisible and can be interpreted as laziness. Action is visible and what is seen is often rewarded. Under this framework, patience is counterintuitive and is an act of humility; action feels good and gives us an illusion of control.

Action is easier when the opportunity for action is easy. We admittedly may have sold some of our best current investments if the opportunity had presented itself at various points along the way. When it comes to compounding and patience, lack of liquidity can be a godsend. Similarly, it’s easier to wait when things are simpler. Complexity contributes exponentially to action – the more buttons there are to play with, the more likely you are to press one.

Yes, we sometimes have to sacrifice in the short-term to keep our eyes trained on the horizon. It’s also worth noting that the tradeoff works both ways; the more other people are impatient, the higher the rewards for our own patience.

What It Looks Like and What It Lets Us Do

“Rivers know this: There is no hurry. We shall get there someday.”

Time pressure can cause anyone to feel cornered, lashing out at anything that looks like a threat and reaching for anything that looks like an opportunity. Trusting yourself to be patient enough to wait for the optimal opportunity requires a deep structural understanding of constraints, resources, capabilities, and potential outcomes. And, at some point, you swing. You swing with intention, awareness, and full commitment.

Based on our operating experiences, self-awareness of biases towards action, and an understanding of how patience can pay off, we have worked to build structure and incentives that allow us to act strategically, optimizing for the long game.

Patient Investments

There is incredible power in having the time and space to strategically and intentionally choose the right investment opportunities…and hold them. In practice, our fund structure promotes the patience to be open and available to unpredictability. Great opportunities don’t show up on a predetermined schedule or at predictable intervals.

This is why we tell investors that we may do five deals in one year or one deal in five years. We just want to do good deals. So we find businesses with durable value propositions, work to align incentives with sellers and operators, and structure terms to set us up to confidently invest for the long-term while unlocking untapped or underutilized capacities. We want to be prepared and available but realistic that good opportunities do not raise their hands regularly.

At the back end, patient investing means no arbitrary timeline to sell and high opportunity costs. Proper patience isn’t necessarily holding forever, but instead applies flexibility – saying you’ll never sell is a form of pride, because there are great reasons, helpful reasons, kind reasons to exit an investment. However, not being a forced seller is always smart, because being forced to do anything is, by definition, suboptimal.

Both entering and exiting investments with patience means allocating and allowing the time and energy necessary to understand which opportunities have the most traction and the greatest potential for impact.

Patient Relationship-Building and Knowledge-Gathering

Patience facilitates and relies on acts of commitment. This is particularly true where private equity intersects with people. Impatience, quick and unconsidered action, and time pressures tempt us to abstract others into numbers and line items, and force them to think of us the same way. If there aren’t deep, long-term relationships (the kind only forged by time, repeated contact and collaboration, and meaningful interactions) we’re only ever going to be able to scratch the surface of what can be achieved. Patience allows us to go deep with people we admire, and that takes consistency of commitment.

Patient relationship-building also recognizes that the people you’re trying to work with are humans with their own wants, needs, fears, anxieties, hopes, expectations, and boundaries. If you’re interested in working with people on a long-term basis and building those relationships, you also have to internalize the fact that, while you can work to align everyone towards a shared goal, you may not always get your way. But if you’ve done things right, the mutual trust and respect built over time will foster shared commitment to see things through, especially in tough times.

A patient understanding and a patient goal of sturdy, sustainable success is the fundamental underpinning of Do No Harm, our first rule of operations. Here, patience means taking the time and putting in the work necessary to truly understand a business’s operations, challenges, and strengths to help address complex issues and create durable impact based on long-term goals and vision. Patience also means taking a wide view, beyond individual choices and actions and interactions and bumps in the road to the more holistic needs, patterns, and contexts. When you collectively understand and adopt a patient mindset, a path to the goal comes into focus.

Patient Impact

Once invested, patience offers flexibility in growth. Time pressure translates to “Grow now, or else.” By contrast, we can recognize where structural improvements, market conditions, talent availability, and strategic positioning can compound over time. Because such planning and structural reinvestment is not nearly as marketable as the in-year result, many of our peers cannot prioritize such focus. These decisions are context- and need-specific, emerge on their own timeline, and require a nuanced approach to action. That being said, they might look something like this:

Establishing new product distribution channels to mirror and expand on previous success.

Optimizing working capital with low-cost lines of credit to free up capacity for long-term investments in growth initiatives

Testing new marketing campaigns to open new lead funnels and increase engagement

Investing in software and technology to improve processes and track outcomes

Preparing for and weathering disruptions in leadership by deepening the management bench

Identifying and investing in new roles with significant value-add and recruiting professionals with the right knowledge, experience, and long-term mindset

Understanding what counts as outstanding performance in a particular company to align incentives and ensure there are fair and transparent compensation plans

Each of these actions requires a great deal of time to be done well – to identify the underlying issues, cultivate buy-in and align incentives, develop a strategic plan, implement the action, and see the benefits and long-term impact. It’s a lot of waiting with the trust that something better is ahead.

To create long-term impact, you must distinguish outputs from outcomes. It’s the difference between the output of a day’s hard work and the broader outcome of years of collective follow through. Each day certainly matters, but a good strategic goal compounds into something greater than the sum of its parts. Operators we resonate with already know this and practice it day after day. They tend to identify with the tortoise mindset (and are deeply skeptical of hares’ shiny object syndrome). What tortoises know is that patience leads to persistence leads to payoff. The best thing we can do is match their durability, grit, and commitment.

Or, as Navy SEALs will tell you, “Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast.”

Why It’s Worth It

“The first rule of compounding is to never interrupt it unnecessarily.”

We’ve baked time into our process to encourage patience because we believe in providing investors, sellers, operators, and ourselves with durability, consistency, and longevity. Our long-term hold period lets us think differently about risk and reward. We are able to align incentives with our investors and our operating partners to figure out priorities and to be responsive and adaptable without having to frantically scramble after every issue. We are able to reinvest in things known to be valuable – building capacity, capability, and readiness.

Our aim in employing patience is to adhere, as much as we can, to the missionary mindset over the mercenary mindset. John Doerr explains the difference like this:

“Mercenaries are driven by paranoia; missionaries are driven by passion. Mercenaries think opportunistically; missionaries think strategically. Mercenaries go for the sprint; missionaries go for the marathon. Mercenaries focus on their competitors and financial statements; missionaries focus on their customers and value statements. Mercenaries are bosses of wolf packs; missionaries are mentors or coaches of teams. Mercenaries worry about entitlements; missionaries are obsessed with making a contribution. Mercenaries are motivated by the lust for making money; missionaries, while recognizing the importance of money, are fundamentally driven by the desire to make meaning.”

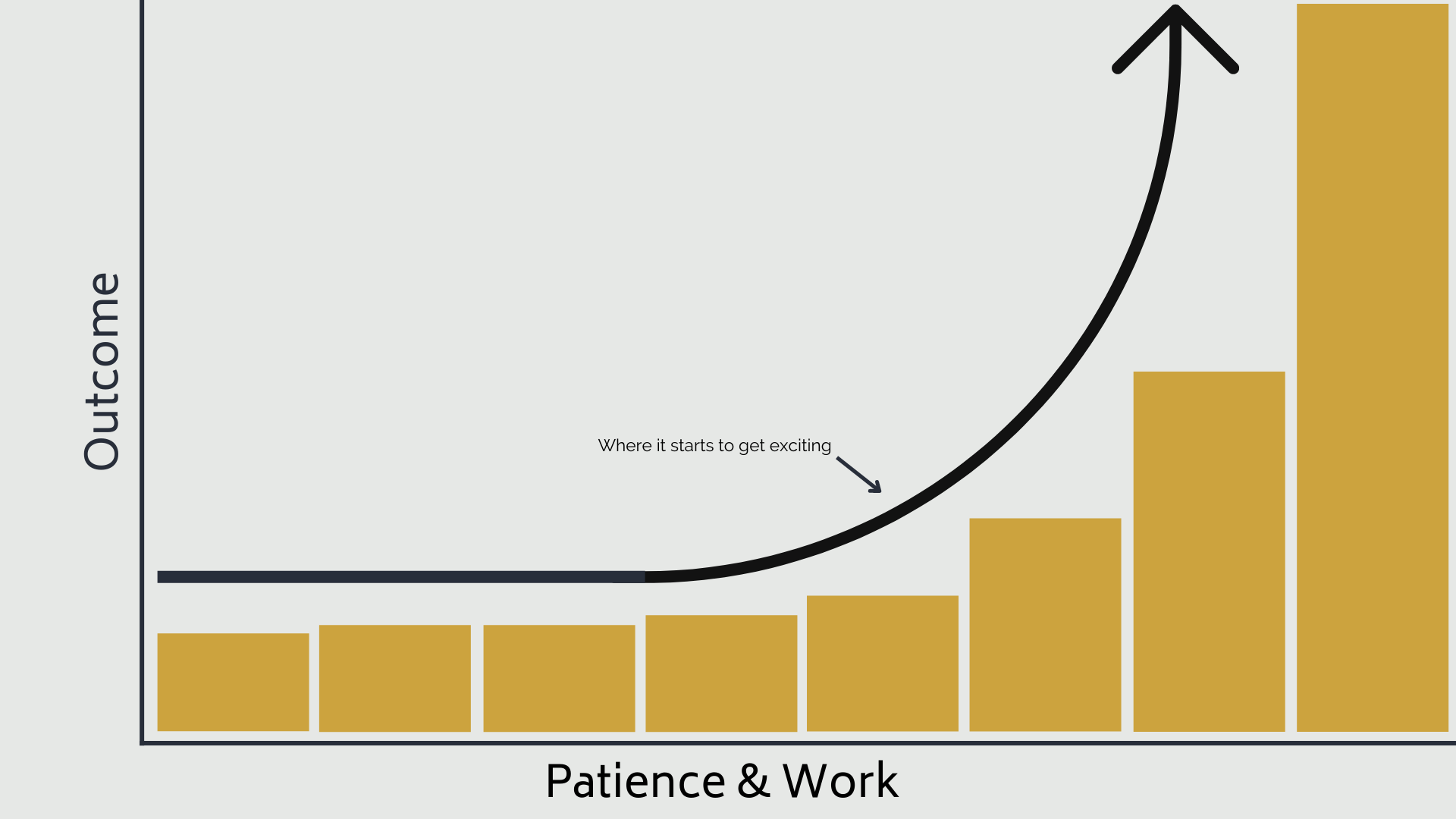

Patience and a missionary mindset show that everything compounds. Compounding looks negligible in the short run and is shocking in the long run.

When it kicks in, compounding looks impossible in all the best ways.

If you work very hard toward a goal you believe in, conclude that there is nothing worthwhile to do in the moment, and have the discipline to be patient while trusting that the time to act will come, you’re building energy and potential – the ingredients necessary to compound.

Our experience and our mindset tell us that being good consistently for a long time is more valuable than being great for a short period of time, even if sprints of greatness get more attention. That’s why, if you need us, we’ll be over here with the tortoises and the missionaries and the vegetables, learning patience and doing the work.

Patience is baked into our Foundations. You can read all of them here.