Portfolio Construction & the Lower Middle Market

Introduction

The answer to how much money, how great an expectation, and how significant a profit is also a moving target and relative to other potential investments.

The definition of investing is to “expend money with the expectation of achieving a profit.” While that’s broadly true, that definition ignores nuances such as how much money, how great an expectation, and how significant a profit. And it turns out those factors are interrelated. For example, if you came across an investment that had a really great expectation to achieve a really significant profit (a “fat pitch” in investing parlance), you would likely want to put as much money as you could behind it. Maybe.

Of course, those opportunities are few and far between.

Also interesting is that the inverse of this has not historically been true. In other words, that one should put no money into an investment that is guaranteed to lose money. In fact, as recently as 2020 there was more than $18 trillion stashed in government bonds with negative yields. That, of course, was during the distortive Covid-19 pandemic when even large and sophisticated investors were willing to take a small guaranteed loss because doing anything else might expose them to larger potential losses.

This is to say that the answer to how much money, how great an expectation, and how significant a profit is also a moving target and relative to other potential investments.

Further, for investors, those questions are like nesting dolls. Because once a person or institution answers them at the highest level (e.g., stocks and bonds 80/20), the question becomes how much in which stocks (i.e., large or small) and bonds (i.e., junk or municipal). And on and on and on it goes. This is what’s called portfolio construction or asset allocation, and it’s hard.

Confounding it all is that there is no right answer to what makes an optimal portfolio. That’s because investments rarely behave as predicted and no two investments are exactly alike. In other words, if I told you to make an investment that would reliably pay a greater than 10% annual dividend, you couldn’t just go buy a mortgage REIT or even an index of them (recent 30-day SEC yield of 12.6%). That’s because the performance of these businesses is volatile and influenced by many factors, as evidenced by the fact that an investment in an index of mortgage REITs over the past five years would have lost money.

Yet despite this uncertainty and ambiguity around portfolio construction, there are some foundations to it:

Know your objective.

Don’t invest more than you can afford to lose.

Diversify, but not too much.

Take risks you’re appropriately compensated for taking.

Remember that the world is more correlated than you think.

Yet while these foundations are generally helpful in thinking about portfolio construction, they are not explicitly helpful when it comes to constructing a portfolio. That’s because, again, investments rarely behave as predicted and no two investments are exactly alike.

So the intent of this white paper is not to prescribe any method of portfolio construction or asset allocation, but rather to walk through each of those five foundations and how they inform how we think about portfolio construction here at Permanent Equity, particularly given our idiosyncratic challenges of investing with a long time horizon, charging no management fees, and sourcing exclusively from the lower middle market.

Know Your Objective.

Knowing your objective means defining how much money you will invest and what the cost of that capital is in order to determine your investment’s capacity and required rate of return.

Before I get to hurdle rates and return thresholds, a short story about my daughter’s u12 girls’ soccer team…

The team moved up to a higher division this season and is therefore playing tougher competition. One recent match against one of those tougher opponents took place on a day when the wind was gusting up to 30 miles per hour. The girls won the coin toss and opted to play the first half with the wind, so the objective in a tie game with the wind at our back was clearly to try to take a commanding lead. To wit, the coach fielded an attacking-heavy portfolio of players and the team ended the half with a 3-0 lead.

But now with a commanding lead and facing a stiff headwind, the objective changed. That’s because all the team needed to do to win the match was not concede three goals. So the coach switched out several attacking players and replaced them with defenders in the back. They won the match 3-1.

Yet at the end of the match, some parents were frustrated. They wanted to know why their player had been subbed out when the first half had been so successful and cited as evidence the fact that the team lost the second half 1-0. And that’s one way to look at it. But the fact of the matter is that winning the second half wasn’t the objective. Rather, the objective was not to lose the second half 3-0 or worse – and while a more attacking-oriented line-up might have won the second-half outright, it would also have been much more likely to concede three goals. The defensive line-up, on the other hand, was highly unlikely to score any goals, but almost assuredly would not concede three or more.

In other words, in building a portfolio, objectives matter. And never try to accomplish more than you are trying to accomplish because in doing so you will expose yourself to asymmetric risk. To use the soccer analogy, the incremental gain of winning the match 6-0 is not worth the catastrophic loss of turning a 3-0 lead into a 3-4 defeat.

With regards to the definition of investing (“expend money with the expectation of achieving a profit”), knowing your objective means defining how much money you will invest and what the cost of that capital is in order to determine your investment’s capacity and required rate of return. Typically, those two things – capacity and rate of return – are inversely correlated. In other words, you are unlikely to find a strategy that can reasonably invest $1 trillion and double your money in a year, so it would be a bad idea to raise that much capital and bank on those returns.

If you’re investing your own money, your required rate of return should be equal to the return you could get taking little-to-no risk at all (i.e., US treasury rates) plus extra return commensurate with the risks you are taking. These risks can take many forms, but are academically calculated using proxies for traits such as volatility, creditworthiness, size, governance, liquidity, and more, which all try to layer in required return in recognition of the fact that a small, volatile, and poorly-managed private company is generally less likely to pay you back than a large, stable, well-run public one.

If you’re investing other people’s money (as we do at Permanent Equity), then they have likely calculated their own required rate of return and agreed to pay you only if you exceed it, so it’s pretty easy in this case to figure out what your minimum required rate of return is. In our case, we take no management fees of any kind and don’t get paid carry until our investors have earned 8% on their invested capital. We then receive a catch-up until we have earned 40% of the returns and after that we split everything 60%/40% until gross returns have exceeded 30%, when we flip and split things 40%/60%.

One way of looking at this is that we shouldn’t get out of bed for anything less than a 13.3% rate of return, which is the rate at which we will have earned our catch-up (8%/60%) and been paid base compensation for our work, and that indeed is a way we look at it. Our objective writ large is to earn a return over time that more than reasonably compensates our investors and us.

Of course, achieving that is more nuanced than investing 100% in things that are expected to achieve that hurdle rate plus because rarely do individual investments perform like they are projected to (some do better, others worse). So typically we try to underwrite things that will perform well in excess of that number in the expectation that we will be quite wrong every once in a while. Further, we demand higher returns from newer investments that are likely to correlate with existing investments because, again, there are diminishing returns from turning a 3-0 lead into a 6-0 win versus a 3-4 defeat.

If, on the other hand, you’re anything from an individual trying to retire to an endowment trying to fund a cause, establishing your objective means defining how much money you need to have at some point in the future, working backwards to determine how much you have now, and then calculating the sliding scale between the return you have to earn compared to the amount of money you need to regularly add to the portfolio in order to have that amount of money at that future time. If you are good at saving (if an individual) or raising (if an endowment) money, then your returns can be lower. If you’re not, they have to be higher.

Either way, if you have an objective and know what it takes to get there, it limits the scope of what’s possible and therefore increases the probability you can achieve it. And also, perhaps more importantly, it prevents you from ever trying to accomplish more than you need to.

2. Don’t Invest More Than You Can Afford to Lose.

Never invest an amount that, if it did go to zero, would prevent you from investing in something else.

When it comes to thinking about how much to invest overall or in any single investment, one universal truth applies: Everything can go to zero. With that in mind, never invest an amount that, if it did go to zero, would prevent you from investing in something else. These are different numbers for different people and institutions, but the same maxim applies: It’s never over if you always live to fight another day.

With regards to thinking about how much capital to put behind individual investments, there are three more things to consider (again, always remembering that everything can go to zero):

How big can it get if it goes well?

If it goes well, what is the net impact if everything else in your portfolio doesn’t?

If it goes poorly, what is the net impact if everything else is fine?

Asking and answering these three questions can help you think about sizing the opportunity and scope the influence on the rest of the portfolio. The reason that’s important is because you want to be thoughtful about not making investments that are too small to matter, but also avoid making investments that are so big that nothing else matters.

For example, one of the smallest investments in our portfolio is a 3% position. Now, it’s expected to punch above its weight this year and contribute 4% of our total return, but run the numbers and that’s only 73 basis points of that return. In other words, was it worth it to make and now maintain an investment that contributes so little today and will shrink from there if it doesn’t grow and still be relatively inconsequential in the scheme of things if it only doubles or triples?

That’s a fair question and when we asked it, we said the answer was yes because the total addressable market of this business is significant and the operating leverage meaningful, so we thought it had multiples more potential. This doesn’t mean it will achieve that potential, but by virtue of having it, this is a small position size that’s worth it.

Contrast that with one of our larger positions, which is 20% of the portfolio and will contribute 30% of this year’s return. We’re happy with that, but we don’t expect the company’s return contribution in dollar terms to grow significantly over time, so the goal with this position was to pay a compelling valuation, but also take a big enough position now so that it was a material contributor both now and in the future when the other companies in the portfolio had grown at higher rates. In other words, we are risking a considerable amount of the portfolio on this position now, but we believe we are being compensated for doing so and also that this concentration risk will be mitigated over time as our other investing decisions play out.

They won’t all play out according to plan, of course, but that’s exactly why we should all invest different amounts in different things.

3. Diversify, but not too much.

If you’re building a portfolio of small, private businesses then you’ll want to be as highly diversified as you can be, but…what makes for diversification in this space can be incredibly idiosyncratic.

Diversification can get a bad rap in the investing community as “diworsification,” which is to say that if you are spreading your bets too thin, you’re not mathematically making any bets at all. Of course, a mitigating factor here when applying this framework to small, private companies is that these companies tend to be volatile and can be at all times a few consecutive bad months away from a crisis. What that means is that if you are trying to build a compelling long-term return stream in our space, you need to be cognizant of aggregating highly disparate assets. Further, knowing your odds of diworsifying among small, private companies is difficult because you can’t practically go out and acquire 100 or more all at once like you can in the public market, so the risk to be aware of is concentration, particularly if it’s inadvertent.

And that’s the twist re: diversification among small, private companies. Ones that look different can actually be quite similar and ones that look similar can actually behave very differently. So what makes a small, private company a disparate asset?

When it comes to public companies, for example, accepted vectors for diversity include size (even though almost all public companies in the overall scheme of things would be considered pretty big), industry, geography, and growth profile/valuation. Among small, private companies, however, size doesn’t really apply, since none are big enough to not be fragile, nor, for the most part, does growth profile/valuation. That’s because valuations tend to cluster around the average and also because, as we like to stay around these parts, no business stays small on purpose, so the growth of any small business in this space is being definitionally blocked by something.

That leaves industry and geography, which both absolutely apply and should often be considered in tandem, though on a more refined scale (e.g., it’s not US versus EMEA, but the Sun Belt versus the Northeast). For example, a pool company in Arizona makes a lot less margin on service than one in the Northeast because in geographies where it freezes and thaws, there is more price insensitive seasonal pool opening and closing revenue. And a fence company in a geography with soft soil will have better economics than one operating in rocky soil because of the throughput on putting up posts.

So if you’re building a portfolio of small, private business, here are some vectors to consider:

Seasonality: A fireworks distributor will generate a much more reliable stream of cash flows when paired with a Christmas ornament manufacturer than it will with a pool toys manufacturer.

Business model: A service company that gets paid upfront will generate a much more reliable stream of cash flows than a construction business that has to try to collect 20% retainage.

Weather: We didn’t realize until it happened how much a rainy month in the Southwest would impact our pool, fence, and waterproofing businesses all at the same time.

Deal structure: If all of your deals have earnouts, it might be a long time before you generate a reliable stream of cash flow, so if you do a deal with an earnout, you might complement it with a deal that includes a preferred return.

People: Your portfolio is significantly riskier if all of your operators want to retire within three years than if they don’t.

The point is that if you’re building a portfolio of small, private businesses then you’ll want to be as highly diversified as you can be, but also that what makes for diversification in this space can be incredibly idiosyncratic. So be aware of what your exposures are and aren’t with the goal of turning inevitable individual business volatility into a more reliable collective return stream.

4. Take risks you’re appropriately compensated for taking.

All of these things are risks, and if you are going to take them, our view is that you need to be compensated for doing so. How do you do that?

We have a joke around the office that we’re in the business of shaving hair. This is in recognition of the fact that small- and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) often come with lots of hair on them in many forms. That can include sloppy accounting, unresolved personnel matters, customer and/or supplier concentration, and even compliance with laws and regulations that is, shall we say, in the gray area. And of course this hair is what can make a business hard to transfer and even uninvestable.

But!

One way to create significant value is to remediate these issues over time, i.e., shave the hair. That’s because in doing so, while you might or might not improve the performance of the business, you’re making it more investable. That increases the size of the pool of potential future buyers, making the business more valuable.

In other words, the less hair the higher the multiple.

To wit, we saw a business recently that had botched an acquisition a few years ago and, in the course of trying to integrate it, had lost and was still losing quite a bit of money. Further, it had been through several rounds of layoffs, revalued inventory, written off assets, and recategorized expenses. The numbers were a mess.

That’s hair.

And while it’s normally not a good thing to lose money with that much hair, what was oddly impressive about this situation was that the core business had been able to fund those losses for so long. What that meant is that the core business might actually be a good one. Or, at the very least, that it could afford to pay for its shave.

So we reached out and floated a valuation and structure to suss out interest and receptivity. The valuation, we thought, was competitive and down the middle, but the structure was admittedly conservative since the valuation baked in righting the botched acquisition and then also refocusing on the core business to grow it.

As for what made the structure conservative, our offer was to pay half of the consideration at close and the other half a few years later contingent on those things (righting the botched acquisition and growing the core business) coming true. Our rationale was that the business was worth one amount if the obvious problems were fixable and a different, lesser amount if they weren’t.

Of course, 50% is a pretty big haircut and the upfront consideration probably undervalued the core business on a standalone basis. But the reason we weren’t comfortable offering a consideration equal to the standalone fair value of the core business upfront is because the core business wasn’t standing alone. Its management was distracted, its cash flow wasn’t 100% distributable, there was the potential for conflict in deciding what to do next, and taking steps to help the core business stand alone would be expensive (severance and lawyers and liquidation processes add up).

All of these things are risks, and if you are going to take them, our view is that you need to be compensated for doing so. How do you do that?

In our line of work we see a lot of what academics would call “idiosyncratic risk.” These are risks that are unique to a situation and so therefore aren’t captured in the risk premia assigned to more widespread factors such as illiquidity, small-size, or equity risk. Examples include:

Inaccurate information risk: We’ve seen businesses that track their inventory in a spiral notebook and also lost track of inventory “back in the 90s.”

Slow feedback loop risk: We’ve seen businesses that don’t close their books until six to eight weeks after the end of the month and others that only do reconciliations quarterly.

Whim risk: We once saw a business whose sole supplier was wholly-owned by a hostile foreign government and another whose sole customer was a big box retailer. In either case, the reversal of course by the counterparty would cause the business to disappear overnight.

Rural risk: It’s really hard to relocate talent to small towns.

Relationship risk: Are customer relationships with the business or with an individual?

The list goes on…

Now, some of these, like whim risk, could metastasize overnight, while others, like rural risk, manifest themselves as more incremental long-term headwinds. But you can take any of them (and we have taken some, but not all of these) provided you are compensated for taking them. Now, if you asked a firm to do an independent valuation, they might look at these idiosyncratic risks and bucket them into an “Additional Risk Premium” that they add to the discount rate when valuing a projected stream of cash flows. And that’s one way to do it, and we do increase our required rate of return as we identify more and more idiosyncratic risks.

But structure is another useful tool in making sure investors are compensated for taking odd risks because thoughtful structures can more effectively account for the potential timing and magnitude of the impact of a specific risk materializing.

For example, in the case of whim risk, the business might disappear overnight. To be compensated for that might mean negotiating a deal structure with a shorter payback period and perhaps attaching a put option as well.

For something longer-term like rural risk, you might ask for some kind of hurdle or preferred return that bakes in the expected growth rate in the event it doesn’t materialize.

To return to our offer of 50% guaranteed at close and 50% contingent and deferred to invest in a turnaround project, we felt that our offer was fair because it compensated the seller appropriately for what had been achieved to date, but also recognized that they were offloading significant risk to us. But offers aren’t made in a vacuum, and in this case we got blown out of the water by someone who offered more than us all guaranteed at close.

Now, that’s a great offer if you want to get a deal done, and in terms of immediate feedback loops, mission accomplished. But is that buyer being compensated for the longer-term risks they are taking or is it the case that we wrongly perceived more risk than was real? Only time can tell on that.

5. Remember that the world is more correlated than you think.

But if it’s true that things become more correlated when they start going really badly, then the benefits of being diversified are reduced at precisely the time you need them the most.

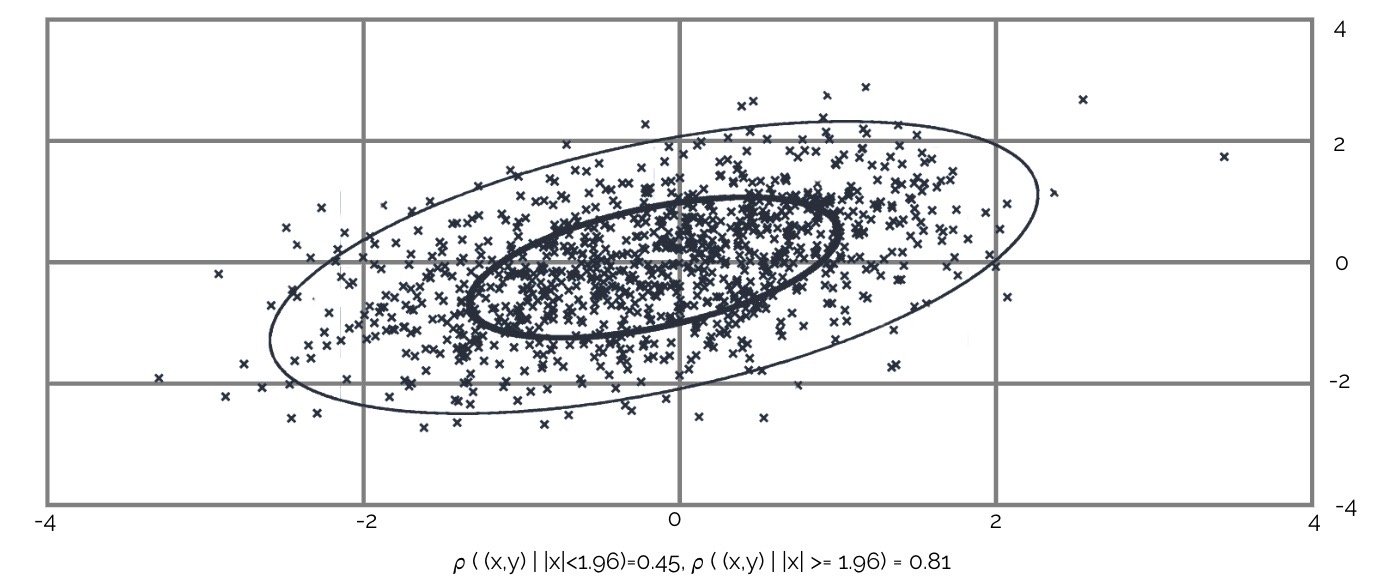

Something I first read a long time ago, but that took a while to understand and appreciate was this special feature from the June 2000 Bank for International Settlements Quarterly Review. Called “Evaluating changes in correlations during periods of high market volatility,” it makes the case, using math, that when things become more volatile, they also become more correlated.

Graph showing why higher volatility events are more correlated because they are less clustered, reproduced from Loretan and English, BIS Quarterly Review, June 2000.

Now, if you’re among the legions of people more intuitively numerate than I am, you might be saying, “No duh.” But for me this was not intuitive. That’s because it seems like one way to think about volatility would be as difference. For example, if lots of things are zigging and zagging all the time, it seems like it should be the case that all of that zigging and zagging would be more random and therefore less correlated.

But another (and the right) way to think about volatility is as magnitude. In other words, something that’s volatile isn’t necessarily zigging and zagging a lot, but rather has the potential for explosive zigs and catastrophic zags. And as the math in that paper shows, while there can be a lot of relative difference between a lot of events in a clustered distribution, extreme events are fewer and a lot more alike relatively speaking precisely because they’re extreme and so they are much more highly correlated.

This is a problem for business and investing because Modern Portfolio Theory posits that you can earn better returns with less risk by doing things that are uncorrelated. But if it’s true that things become more correlated when they start going really badly, then the benefits of being diversified are reduced at precisely the time you need them the most.

And this is a reality that has proved to be true during significant market dislocations.

Graph showing the average correlation of capital appreciation returns for all available markets, reproduced from Goetzmann, Li, and Rouwenhorst, “Long-Term Global Market Correlations,” NBER Working Paper Series, November 2001.

This National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, “Long-Term Global Market Correlations,” was published in November 2001, just as the bursting of the tech bubble and 9/11 terrorist attacks were wreaking havoc on global markets. It remarked that “the diversification benefits to global investing are not constant,” that “diversification potential today is very low compared to the rest of capital market history,” and that “periods of poor market performance, most notably the Great Depression, were associated with high correlations, rather than low correlations.” Global correlations increased again with the 2009 financial crisis, and during Covid everything went way down then way up together.

Table showing the correlation between global indexes from 11/1/07-10/31/12, reproduced from “Why Have Global Correlations Increased?” Morningstar, November 2012.

Table showing the correlation between indexes post-Covid (from 1/20-12/22), reproduced from “The Correlation Conundrum,” Swan Global Investments.

In other words, it’s clear that when people panic, they’re likely to panic about everything all at once.

And while there is less academic research into how this propensity manifests itself in small operating businesses, I can tell you from experience that when something starts to go poorly at a small operating business, a lot more is likely to go poorly alongside it. A business that loses a bunch of money on a project, for example, might see performance suffer at other projects as it repurposes its best people to deal with the crisis. Then its controller, stressed out by the situation, might decide to retire a year earlier than expected, leaving a massive hole on the leadership team right when accurate numbers are most important. And seeing deteriorating prospects and a lack of appetite for growth, a star salesperson might then leave for a competitor. Heck, it’s when morale is low that office supplies even start to disappear.

When it rains, as they say, it pours.

So if the lesson is that the world is more correlated than we think, an implication is that we can’t engineer our way to stability when constructing an investment portfolio or building a business. Instead, we have to accept that there will be instability and that when it happens, there will be a lot of this at once. The two ways to handle this are (1) temperament, i.e., know ahead of time what you’ll need to do to keep your cool, and (2) structure, i.e., your agreements with others and liquidity requirements can never turn you into a forced actor.

Portfolio Construction & the Lower Middle Market: Final Thoughts

Either you or the world is always moving on. You to different objectives and ambitions, and the world to different bubbles and busts.

If there is a key to all of this, it’s to keep your cool and never put yourself in a position where you are forced to act. The reason that’s so is because every other bit of portfolio construction advice will eventually be dated. Either you or the world is always moving on. You to different objectives and ambitions, and the world to different bubbles and busts.

An aspiration we have around the office at Permanent Equity is to do what makes sense 100% of the time and what doesn’t make sense 0% of the time. We don’t always achieve that of course, because we’re human, but that’s why aspirations are aspirations. A likelihood, however, is that we’ll never get there because what makes sense for the future is perhaps not what made sense in the past. So be intentionally pragmatic as you build your own portfolio, and I hope you found our weird way of thinking about our own weird world helpful.

By Tim Hanson

Disclaimer: The information, opinions and views presented in this writing are being provided for general informational and educational purposes only. They should not be considered as legal, tax, financial, or other professional of any kind. All such information, opinions and views are of a general nature and have not been tailored to and do not address the specific circumstances of any particular individual or entity, and do not constitute a comprehensive or complete statement of the matters discussed herein.

Readers should consult with their own legal, tax, financial, or other professional advisors regarding the applicability of this information to their own circumstances. It is important to remember that historical performance is no guarantee of future returns and that investing inherently carries risks. No representation is made that any specific investment or investment strategy directly or indirectly made reference to in this writing will be profitable or otherwise prove successful.

This writing is not and should not be construed as an offering of advisory services, or as a solicitation to buy, an offer to sell, or a recommendation of any securities or other financial instruments.