The Micro PE Reality Check

Private Equity is a broad umbrella. Technically, the transfer of all ownership in non-public assets is “PE.” So it can be confusing when an owner of a couple laundry mats sees companies sell for “ten times,” only to find out his assets are worth a small fraction of that amount.

Breaking PE down into segments provides a better understanding of reality. The market for a $50M-earning multi-national private corporation is starkly different from a $3M-earning regional construction firm. And the markets for both are worlds away from the laundry mat mini-chain.

Every quarter, the International Business Brokers Association (IBBA) and M&A Source in conjunction with Pepperdine’s Private Capital Markets Project releases a report called Market Pulse. It explores the markets on the lowest end of PE, broken down into the following segments based on profits: 1) Less than $500K SDE, 2) $500K - $1MM SDE, 3) $1MM - $2MM SDE, 4) $2MM - $5MM EBITDA and 5) $5MM - $50MM EBITDA. In terms of quantity and consistency, there’s no better data curated on the micro-PE market than this report.

With that said, no data set is perfect, nor bias-free. Deals that don’t get done aren’t counted, lumping all industries together creates a blunt instrument, and only intermediaries typically report, meaning non-intermediated deals aren’t included in the data. The intermediaries that report the information typically work on smaller deals. We suspect the $5MM - $50MM EBITDA category skews heavily towards the lower end of that spectrum. In this data set, we stop drawing conclusions above the $10MM EBITDA mark.

Here are a few thoughts based on the latest report:

NEW SBA RULES

“New SBA rules lowering minimum down payments from 25 percent to 10 percent will have a positive impact on the market.”

If I was going to start over financially, with what I now know, I would buy a small business with an SBA loan. That’s how I bought my first business, largely by accident. While you have to tolerate a little higher interest rate and some government fees, the loan terms are outrageously long-dated (10 years), providing significantly more breathing room for cash flow.

The challenge in securing an SBA loan is coming up with the down payment, and this rule change is more significant than it appears at first blush. It lowers the amount of equity needed to close a transaction by 60%. And, the new rules only require 5% in cash from the buyer. Said differently, you can buy a lot more business for your equity.

There’s a joke that banks are fantastic sources of financing as long as you don’t need the money. And, it’s mostly true. Banks’ downside is big and their upside is relatively limited, especially on small deals. Remember, small deals are not easier and transaction costs are dramatically higher as a percentage of purchase price. Therefore, most banks with cash flow-based lending expertise shy away from small deals, and most banks willing to do small deals don’t feel comfortable lending to micro buy-outs. This creates a challenging dynamic for small transactions, and is one of many reasons the market remains highly inefficient.

This rule change will allow individual buyers with less resources to buy out larger companies, and I’d expect this to be a tailwind for sellers with under $2MM in earnings over the next couple years. Why only under $2MM? Because the SBA limit is $5MM. Even at max leverage, this means that you’re likely buying a company with less than $2MM in earnings, or got creative in the structure.

If I’m interested in buying a small company and just getting my start, this is welcome news.

BUYERS

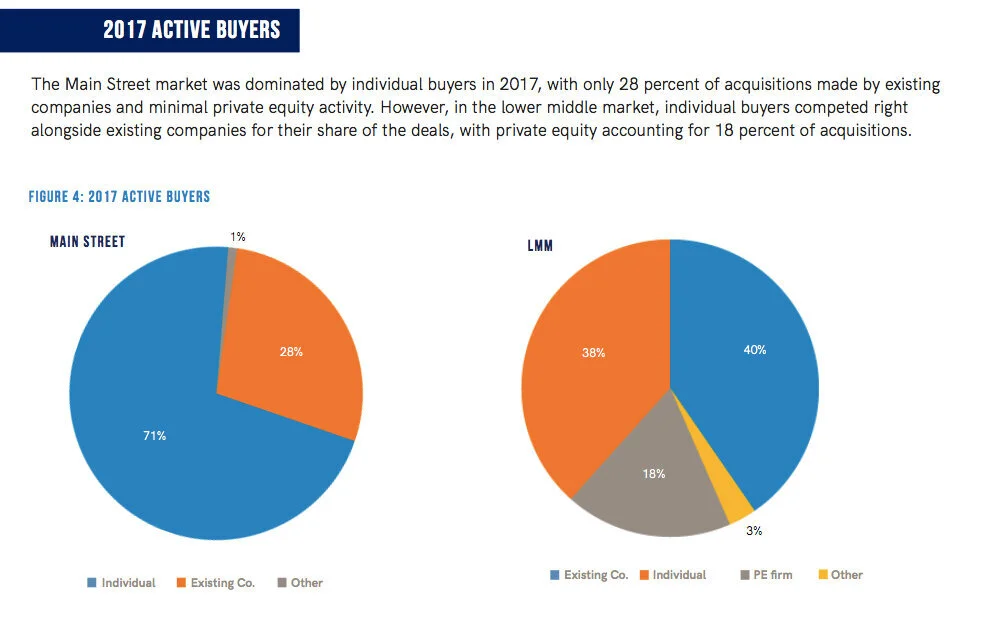

It’s a common misconception that private equity firms are “playing down” based on all the capital that has been raised. If they are, they’re doing a great job hiding. Here’s the breakdown of buyers based on two categories: Main Street (< $2MM earnings) and LMM ($2MM to $50MM earnings). PE firms don’t touch things under $2MM in earnings and are less than 20% of the buyers for companies up to $50MM in earnings. Wealthy individuals, impliedly without professional organizations around them, are the bulk of buyers.

These stats scream inefficiency. Most businesses are sold and bought by accident, kind of like my first transaction. It’s largely a product of serendipity, Google-and-figure-it-out, and oblivious risk-taking. At least, that’s what it was for me.

WHY SELL?

“Many just can’t let go emotionally, and it’s one of the most common mistakes we see, eventually leading to business decline.”

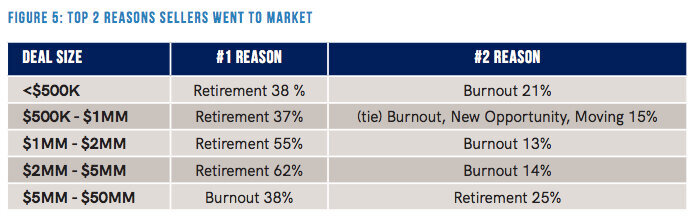

One of my favorite stats is around the motivations for why owners sell — retirement and burnout. To take a step back, these motivations are basically the same thing, with burnout being less age-driven.

The big takeaway is that sellers don’t sell because someone comes along and offers them money. If you’re making $1M/year, you’re not (usually) desperate. Owners sell because they don't want to be running, or can’t run, the business any longer. And yet, there’s a whole industry built around cold-calling and spamming sellers in an effort to convince them they should sell. I’ve always found it baffling. If you’re a business owner, I apologize on behalf of my industry for the 3 to 5 phone calls a week that you receive.

P.S. As you can see below, most owners don’t put much thought into planning ahead.

MULTIPLES, PRICE, AND HYPE

“Year-over-year, multiples saw modest declines in all but the largest market sector, where multiples remained stable.”

Not a week goes by when I don’t have someone tell me, “Well, the good times aren’t going to last. Multiples are exploding.” First, I don’t remember the “good times.” I remember slogging it out, inch-by-inch. Second, multiples aren’t exploding. In fact, on deals that actually close they’re off-peak and stable, if not declining.

Are there more buyers in the lower-end of private equity? Sure. That’s the natural result of one of the longest economic expansions in history. But you have an even stronger countervailing force: ownership being concentrated in aging Boomers. Ultimately, there’s only one outcome I can see — the rate of sellers increasing much faster than the rate of buyers, independent of the economic cycle.

I believe these trends are already showing up in the numbers below. Multiples aren’t increasing, even in the coveted $5MM - $50MM range, and they should be based on where we are in the economic cycle.

MYTH OF THE QUICK CLOSE

Another prevalent narrative is the idea that a “good buyer” should be able to close a transaction within 60 to 90 days of executing a letter of intent. The insinuation is that if you don’t expect to close that quickly, there’s a buyer who will, and we’ll go with them.

Heck, there’s even a product out now called “reps and warranties insurance.” The pitch is an insurance policy that pays out if the seller breaches a promise, allowing the buyer to close a deal more quickly (Look kids! No hands, err, I mean due diligence!). Isn’t the point of due diligence to make sure you know what you’re buying? Call me old school, but Permanent Equity is going to stick to the Ronald Reagan approach: “Trust, but verify.”

While I have no doubt there are more talented due diligence teams out there, especially considering I lead our team at Permanent Equity, it’s pure fantasy to think the norm is 60 to 90 days. As the chart below shows, deals take time. And remember, these are averages.

For instance, in our segment of the market, the base rate is 5.5 months after an LOI is signed. Said differently, it takes a long time to get a deal closed after all the material economic terms are set. That means it’s not unreasonable for deals to take 6 to 8 months to close. And remember, the sample is selection-biased. The deals that don’t close after a year of trying aren’t counted. Our most recent deal took quite a while, and that’s perfectly fine by us.

We plan to be partners in a business for decades. What does it matter if due diligence took a few months longer? Is the alternative, everyone stressed out, sleepless, and hard-charging towards the quickest close possible, a better path? It sounds like a terrible way to set up a long-term relationship to me.

Remember, sellers are simultaneously running the business and participating in due diligence. It’s not a stretch to say it’s two full-time jobs for most senior staff. As a buyer, we want to close on a healthy business, obviously. We’ve found that allowing the sellers to take it a little slower helps ensure the business remains strong.

One of the advantages we have at Permanent Equity is that we don’t usually close a deal with financing. I know, I know. It’s really weird. The cash at close is typically all equity. This dramatically reduces outside friction. Most lenders require specific, extensive due diligence that we (mostly) find irrelevant. Plus, it’s an extra gatekeeper you have to get a “yes” on to close the deal.

Adding another decision-maker isn’t additive; it’s multiplicative. I can’t imagine the skill required to get a deal done with a senior lender and a mezzanine lender. Throw in an independent board of directors, opposing legal and accounting teams, and attorneys for the senior executives and consummating a deal requires an act of God. No wonder the vast majority of deals with a signed letter of intent don’t close.

SEARCH FUND SYMPATHY

Another interesting tidbit in this data is how long a deal takes to develop. The norm is a year. This means that if you do about average, a deal you look at today would close in twelve months. That sounds about right to me, if everything goes well. Currently, we are working on a deal we first saw almost four years ago. Another opportunity has been in the hopper for eighteen months.

Because of our structure, we can withstand the irregularities, but my heart goes out to independent sponsors and search funds. I can’t imagine the stress that must come with having to spin up deal flow from a standing start, select/negotiate it, and execute a transaction within two years, with little direct experience and no team. Heck, most days it feels like we’ll never do another deal and there are eight of us fully focused on it.

The bottom line is deals take time, far more time than you’d expect. The number of factors that must come together is astounding and the ground is constantly shifting. My advice to someone interested in buying a company for the first time is to have at least three years of runway available. The first year will be spent generating opportunity costs. The second year will be spent negotiating, re-negotiating, diligencing, and likely failing to close a deal. The third year is when something from the first year comes back around and can get done.