There Is No Medium Risk

Google isn’t the arbiter of truth in this world, but it is an arbiter of truth, and if you google “medium risk investments” today, here’s what the search returns at the top:

Really?

Sure, “medium risk” is an appealing profile. It implies a good return opportunity and a lower chance of losing your money. But look at those medium-risk opportunities. Crowdfunded real estate? Yes, real estate has tangible value, but a crowdfunded deal means the professionals passed (not a great sign). And maybe you heard that interest rates are rising. That makes the carrying cost of real estate that much more expensive. As for dividend-paying stocks, describing them as medium-risk is painting with broad brush strokes. Some fund their dividends through debt, meaning their yields are just eating up their equity, while others, such as mortgage REITs, take on real risks to fund payouts.

Corporate bonds and preferred stocks? Those are just more senior securities on corporate cap tables, which means you are capping your upside in return for that position. But, even if you’re senior, good luck getting your money back if a company goes bankrupt.

And municipal bonds? There are tax advantages, but talk about a situation with more downside than upside. That brings us to risk.

When we last wrote about risk, we defined it as the “likelihood and magnitude of permanent loss.” But what have we reaffirmed about risk in the seven(?!) years since we wrote that piece? It’s that anything can (and will) go down substantially in value, and maybe all the way to zero.

In other words, there is no such thing as medium risk.

All investing is taking risks

But there is more nuance to it than that. Improbable things happen more often than you’d think, and probable things frequently fail to happen; that’s uncertainty, and uncertainty is at the root of risk. In fact, we concluded our last go-round on this topic by saying that rather than walking on the risk high wire we preferred our companies on two-by-fours about six inches off the ground.

-

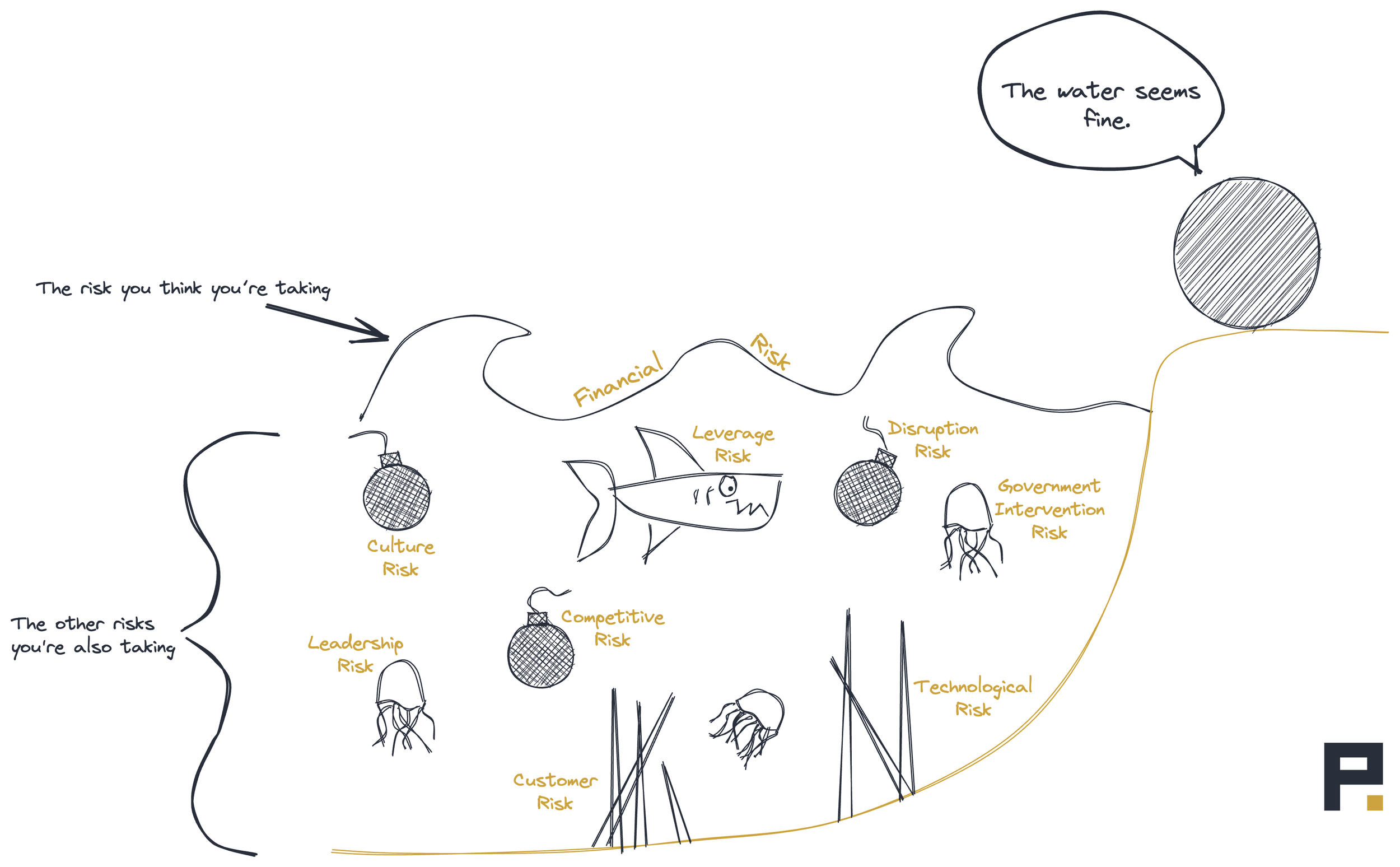

What you’re trying to do is understand the type, magnitude, and probability of the risk you’re taking — each of us has some risks that are bigger than others, and some that matter more than others.

Competitive Risk: How high is the possibility of outside risks from competitors? What’s the chance that your competition’s actions will negatively impact your own business?

Technological Risk: How much will a technology failure – phishing, data breaches, old equipment – affect your business?

Government Intervention Risk: What’s the likelihood that regulations, oversight, or agency action will impact your business? How much will potential legislation affect your company and its operations?

Culture Risk: How robust or fragile is your company culture? Its expectations? Its transparency? How much impact does one person have on it? How likely is it that rivalries, factions, or turf wars will form?

Leadership Risk: Who’s in charge of the company matters more in some companies than in others; what is the probability that the leadership team you’re backing will fall apart? What’s the magnitude of that loss?

Disruption Risk: How susceptible is your business to disruptive events, either man-made or natural disasters? What are the likelihoods of different kinds of disruptive events and which are of significance to you? To your customers? To your suppliers?

Leverage Risk: What’s your appetite for leverage? Is borrowing additional capital more likely to enhance your gains or compound your losses? Under what conditions is the outcome probable to go one way or the other – and how far can it swing before you’re in permanent loss territory?

Customer Risk: What types of customers are you serving? Does any single customer account for an outsized proportion of your revenue? What is the probability that that customer disappears, takes their business elsewhere, or otherwise no longer needs what you supply?

Supplier Risk: On the other side of your business, what threats face your procurement activities? To what extent are you reliant on a small pool of vendors or service providers? Would failure of a key supplier prove a minor inconvenience or fatal?

Volatility Risk: Does your situation (industry, company, circumstances, outlook) bear fluctuation well? What’s the likelihood that temporary downward swings will become permanent? Or that you can capitalize on variability?

Model Risk: Can the process you want to model actually be modeled? How likely is it that the model is accurate enough to be useful? What happens if it turns out you’re using the wrong model?

Materials Risk: How much is your business dependent on materials? What’s the impact if there are supply chain disruptions, volatility in costs, or quality concerns? Which are most likely? Which matter most?

Inflation Risk: What happens to your decision-making if inflation rises? How much will that affect your purchasing power? To what degree does inflation affect your prospective returns, or interest rates, or valuation?

So, if you thoughtfully consider these (and many other) possible risks, what are the risks you’re really taking?

Given that, you might think we are advocating for a low-risk approach. In fact, we love risk. We don’t eschew risk either in our operations or our investments. Instead we acknowledge that everything is risky. No business can expect to win big long term while only trying to walk on two by fours six inches off the ground. Rather, what we’ve learned is that we want our business walking on moon shoes (that’s a terrible analogy, but the point is we want to make decisions where we don’t have far to fall but have lots of room to jump). Therefore we want to do things that not just compensate us for the assumed risk we are taking, but could pay off huge. (Note to regulators: This is not a forward-looking statement nor an indication of future results, but a mindset.)

In her book Thinking in Bets, which is fundamentally a meditation on how to think more purposefully about risks and to better understand the risks you’re taking, Annie Duke writes, “We routinely decide among alternatives, put resources at risk, assess the likelihood of different outcomes, and consider what it is we value. Every decision commits us to some source of action that, by definition, eliminates acting on other alternatives. Not placing a bet on something is, itself, a bet.”

So if everything can go to zero, including not doing anything at all, we think you should only bet on things that have the optionality to go really, really well if they work.

What that’s not

Over the years, we’ve reviewed thousands of construction companies. The industry was boring, it made money, and it was in demand. But here are two truths we’ve learned about construction:

It’s very competitive.

When things go bad, they go really bad.

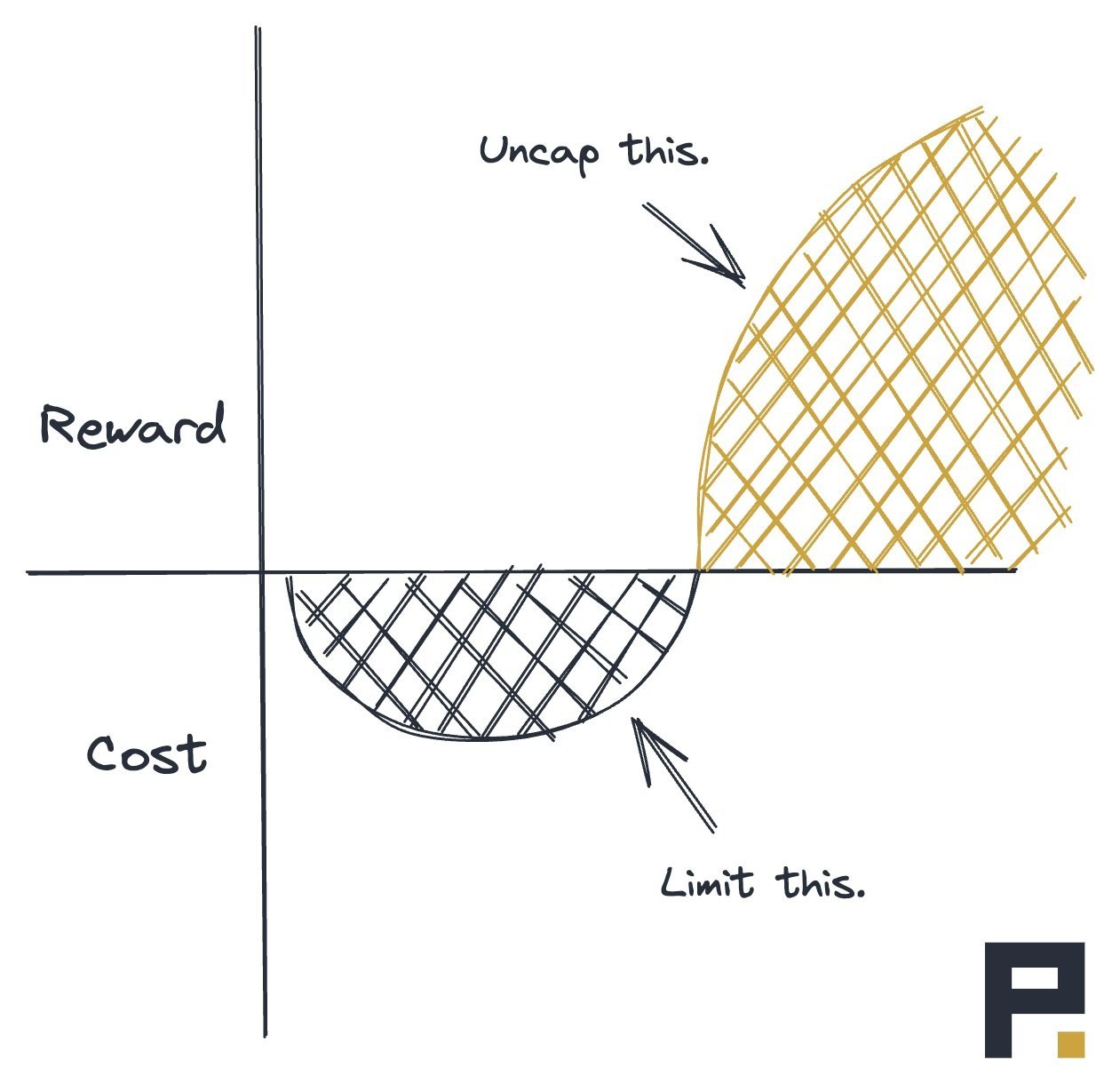

The reality of those truths is that most construction companies have a capped upside and unlimited downside. If you’re the best in the world, your margins are limited by the pricing of your competitors’ bids. Yet if you’re on a big project and things go wrong, you have nearly unlimited downside in order to make things right and avoid liquidated damages. Further, things can go wrong for lots of reasons outside of your control. If you’re drafting business models, that’s not one you’d take with the first pick. It’s all downside variance.

What would you take with the first pick? If you believe there is no medium risk, then that would be something that has the potential to go to the moon if things go well. We call this upside variance.

A business with upside variance would be asset light, require minimum reinvestment, get paid upfront, have recurring revenue and high margins, and be marketed by word of mouth. While we readily acknowledge that that specific business or investment does not exist, businesses and investments with those characteristics do – then the amount of upside variance you capture as an operator or investor becomes a function of what you pay for it.

Price is what you pay, upside is what you get

-

How you think about risk is intimately related to how you think about the long term. We regularly talk about the fact that there are some businesses we would have sold at various points if we had had an option to do so. While we’re committed to long-term thinking and acting, that commitment is sometimes supported by an unintentional Ulysses contract – our hands are tied against the call of a siren’s song (or the screech of a risk that looks like it’s on its way to zero in the short term).

To illustrate through another mythological reference, if you make a list of all the potential risk areas, it’s easy to feel like you’re flying too close to the sun… all the time. Equally risky is the inverse: under-appreciating the impact of one or more elements of risk.

For every decision you’re making, there’s a vast buffet of risks you’re taking. From that smorgasbord – and this is the important part – you’ve got to determine what the controlling factors are for you. What factors do you care about for success, even if everything else goes to hell, and what factors must go right for you to say a risk has paid off? And what, really, are you betting?

These are the things where you say “If we get those right, we can accept almost any other types of risk. But if we get them wrong, there’s no amount of upside that will make up for it.”

Articulating these non-negotiables – really knowing them and not underselling them – forces you to think about what it means for a risk to pay off for you and your company, even if that payoff doesn’t meet others’ definition of success (or your keep-you-up-at-night risk doesn’t meet others’ definition of risk).

For most of us, everything’s framed against price. In fact, we’ve come to believe that paying a high price for something is effectively the same as levering it up: you put pressure on people to perform and shorten your time horizon to deliver that performance.

But “price” is more than dollars. It might be any one of a number of controlling factors: opportunity cost, culture fit, customer/supplier concentration, etc. In any business relationship you enter into there’s the cost and a range of potential rewards.

To share just one example, we invested in a business alongside a materially involved owner, but we got comfortable with the key man risk because he was committed to staying involved and building out a management team over 5+ years. The deal was structured to honor that commitment. And then, in an unfortunate turn for much more than our deal, he got sick. It turns out, no matter how well-intentioned all parties are, you can’t control the universe through a purchase agreement.

If you can minimize the cost and tilt the range up and to the right, you win. But if you cap your upside in a world where there is no medium risk, you will inevitably lose. Or as Warren Buffett described his decision-making process: “Take the probability of loss times the amount of possible loss from the probability of gain times the amount of possible gain. That is what we’re trying to do. It’s imperfect, but that’s what it’s all about.”

So here’s the triangulation: What’s the downside of the decision? What’s the upside? And what’s the price you pay? With those variables outlined, the point is to try to create more upside variance every day.

Disclaimer: The information, opinions and views presented in this article are being provided for general informational and educational purposes only and are not intended to constitute and do not constitute legal, tax, accounting or investment advice of any kind. All such information, opinions and views are of a general nature and have not been tailored to and do not address the specific circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Nothing in this article constitutes professional and/or financial advice, nor does it constitute a comprehensive or complete statement of the matters discussed herein.

For more musings on risk and reward, subscribe to Unqualified Opinions, a daily newsletter from CIO Tim Hanson.