Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions delivered to your inbox.

Man United, the Cowboys, Buffett, and Ice Cubes

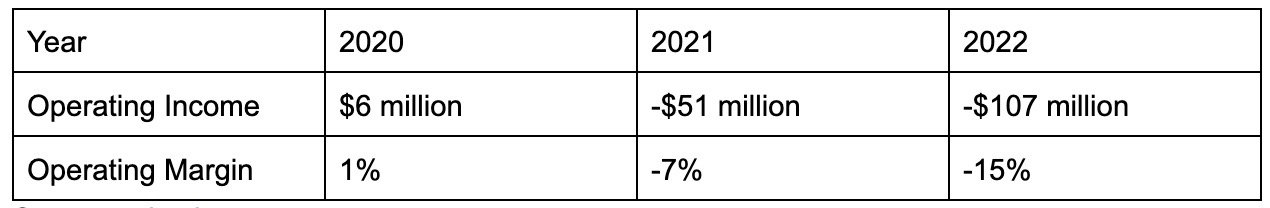

Manchester United is one of a handful of publicly traded sports teams. Its current enterprise value is approximately $6 billion, which is the price that investors have recently offered to pay to buy the storied soccer team. So Manchester United must be making a lot of money, right?

Not so much…

Source: roic.ai

Why is an asset with that financial profile worth so much? The answer (and as an Arsenal supporter it pains me to say this) is that there’s only one United.

In finance parlance this is an example of an irreplaceable asset, something that you could never recreate from scratch even if you had unlimited capital. But that begs another question: If Manchester United is an irreplaceable asset, why isn’t it worth more than $6 billion?

Being worth $6 billion already makes ManU one of the 10-most valuable sports teams in the world. And while it is itself irreplaceable, there are similar assets like the Cowboys, Yankees, Lakers, or (ahem) Arsenal. So ManU’s value in the eyes of potential buyers is capped at the point where paying a premium for ManU isn’t worth it relative to what one could pay for a different professional sports team.

Frustratingly, this number is not a known arbitrage and can be influenced by all kinds of factors: location, history, league, wins and losses etc.

I used to think that buying a sports team was something ultra wealthy people did to demonstrate status and entertain themselves. But since Jerry Jones bought the Dallas Cowboys for $150 million in 1989, he has earned a very respectable 13% annualized return on his investment (for context that’s what Warren Buffett has generated at Berkshire Hathaway over the same period).

But if you’re going to make an investment like that, you have to know full well going into it that you won’t monetize it until the end of your holding period. The reason is that if you’re building an irreplaceable asset, it makes sense to plow all of your earnings back into it to make it more and more irreplaceable (as sports team owners do by signing players, building stadiums, updating their logos, etc.).

Said differently, if you buy a sports team to make it cash flow, you’ll undermine the value of your own investment because in the course of not spending on players and stadiums you’ll start losing games and fans and end up making the asset replaceable.

On the other hand, if you have an asset that’s a melting ice cube, like the pager business has been from the 1990s until today, you should absolutely maximize your annual cash flow distributions so you can do something else with the money that asset generates before it disappears.

Of course, these are examples of business types where making decisions about capital allocation are binary and easy. Most of the real world operates somewhere in between.

— By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Why is Insurance Legal?

Somebody sent me Geico’s list of unusual insurance policies the other day and asked me how I might price them. Leaving aside the throwaways like alien abduction and werewolves (although there is absolutely something to be written on alien abduction insurance), there’s some food for thought in there.

Think about ransom reimbursement insurance, for example. You’d want to know things like where that person travels and how likely kidnappings are of a person of that profile in that area. You’d want to try to estimate what the ransom demand might be. And you’d probably want some kind of dynamic pricing model or ability to reset rates given that the odds of those variables could change on a dime.

Of course, the price might also change if you were able to get the insured to agree to do things (like not travel to places where they were likely to be kidnapped) that reduced the odds of a claim. But while people typically don’t buy insurance so they can’t do things, there are likely some things they would never do anyway that they are willing to agree to:

Markel is not Geico, but it is a wildly successful specialty insurance company, and I had the opportunity to see its then CIO and now co-CEO Tom Gayner speak at an event some years ago. He ended up discussing the company’s successful business insuring competition fishing boats (i.e., small boats with big engines that are dangerous). The reason, he said, that they were so good in this space was because they had started in it early and kept very good records, so they now had a proprietary data set that let them price the risk of insuring these boats better than anyone else.

That’s a real edge (data!) and when you have one of those you need to push it as far as you can, as Markel has done in the marine insurance space.

What’s the point? Insurance is basically reverse gambling. In gambling, you pay small amounts of money to hopefully win big ones, but your expected value is negative because you probably won’t win anything. In insurance, you pay small amounts of money to hopefully avoid losing big ones, but your expected value is negative because you probably will pay more into the system than you will ever get out of it.

When it’s put that way, why did the government for so long prohibit gambling while requiring insurance? Part of the answer to that has to do with the difference between upside and downside, I get it, but both are scams in the sense that the house has a huge informational advantage over the customer in such a way that it makes the transaction inherently one-sided. If you’re buying insurance, in other words, you’re probably getting duped.

This is why I hate insurance and would rather self-insure against any event that is controllable and/or affordable. But insurance does have its place in protecting against uncontrollable events that might lead to bankruptcy (which is why I’m not lobbying too hard to get rid of it).

When it comes to insurance, or really anything, think about your tolerances and your data and your exposures and your costs. If you bet blind, you’re likely to lose, but the catch-22 is that even if you bet smart, you could still lose. So maybe just get the high deductible plan?

— By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

How to Conquer the World

One of my more popular tweets was when I calculated the ROICs of the various Monopoly properties. I think this was mostly because a lot of us are competitive nerds at heart, but it was also winter at the time and Covid and so it resonated.

More recently, I’ve gotten into playing Risk. We’ve long had Risk as a board game, but it was tedious to set up and took forever to play and so we didn’t. Those problems were solved, however, when a colleague got us a version that we could play on the Nintendo Switch while we were quarantined. The reason the video game version is so much better is because it sets up everything automatically and you can play at pace.

If you’re not familiar with Risk, here are the things you need to know for the rest of this to make sense:

You’re trying to take over the world by conquering countries.

You do that by placing armies in countries and attacking neighboring countries.

When you attack a neighboring country, you and your opponent roll the dice. If your number is higher, the opponent loses an army and vice versa but the number of dice one gets to roll depends on the number of armies one has. In other words, there is both skill (the number of armies attacking) and luck (the roll of the dice).

When you conquer a country, you get a card.

When you defeat a player (i.e., they have no more armies left anywhere), you get all of their cards.

You can trade cards in for more armies and the more cards you trade in the more armies you get.

As with anything, there’s more nuance than that, but that’s the gist. In playing so much Risk, three clear strategies have emerged:

You have to conquer a country on every turn to have a regular flow of cards.

If you have a chance to defeat a player who has cards, you should trade in your cards and take significant risk to do it.

If you don’t have a chance to defeat a player, you should wait to trade in your cards until you max out the number of armies you get in return.

There are real world applications of these. They are:

Always be creating optionality.

Invest in anything and everything that has positive expected value and rapid payback.

Absent rapid payback, do very little until there is maximum return potential.

You may still lose, but you’ll go down swinging.

— By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Stupid Accounting Tricks

I enjoyed this SEC enforcement action against electronics manufacturer Gentex and its CFO Kevin Nash (no, not that Kevin Nash)…

I enjoyed this SEC enforcement action against electronics manufacturer Gentex and its CFO Kevin Nash (no, not that Kevin Nash):

The total market capitalization of the US stock market is about $40 trillion. In many ways the country’s financial security depends on it. And yet in others it is just absurd financial theater. Is it just me or is the fact that professional adults are engaging in these kinds of meaningless shenanigans on the margin to hit an arbitrary target devised by other professional adults and that there are still other professional adults whose full-time job it is to catch them a sign that something has really gone off the rails?

Maybe it’s just me. Have a great weekend.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Work in the Real World

Occasionally one of our investors will call us and ask "Hey, how's it going in the real world?" which is a clever way of alluding to the fact that…

Occasionally one of our investors will call us and ask "Hey, how's it going in the real world?" which is a clever way of alluding to the fact that our portfolio (waterproofers, pools, fences, etc.) may not look a lot like the rest of their portfolio (tech, startups, and levered exotics). But we like being in the real world even if it's a bit passe.

So I was interested when Suzy Welch wrote recently in The WSJ about an MBA class she's started teaching at NYU. In it, she bemoans the fact that so many smart people get advanced degrees and go into one of big tech, consulting, or high finance, where they sell advice and services but not "real stuff." Their choices make sense, though, because the pay is good and the title strokes the ego.

But she also chides other sectors for not actively recruiting these people on campus. And that's a fair point too, but side by side real companies don't tend to compare favorably to glamorous ones. For real companies the action is out in the field and not behind a booth at the student union.

The talent problem in the real economy is real though and it's particularly acute at small, real companies like the ones we invest in and even more so if that small, real company happens to be in rural America. Yet the jobs, while challenging, are fun and the upside tremendous if you can get it right. It's just at the outset small companies don't have the resources to commit to eye-popping base salaries.

We have one Kellogg MBA/Deloitte refugee in our portfolio, though, and I don't think she'd mind me saying that she has had a blast building a company with us and is excited about where it's going. Were we the most attractive offer she had when we brought her on board? Maybe not. The difference, though, is that I think we offered a wider range of potential outcomes and that she was willing to bet on herself.

— By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Brain Arbitrage

Brent (our CEO) called me the other day and said “I had a dream last night that we moved the firm to San Francisco and were wildly successful, so let’s make it happen.”

Brent (our CEO) called me the other day and said “I had a dream last night that we moved the firm to San Francisco and were wildly successful, so let’s make it happen.” And that’s why we’ve started the process of closing up shop here in Columbia, Missouri, and moving the team out to California…

Of course, that would never happen. There may be merits to Permanent Equity having an office in California, but the fact the CEO dreamed about such a thing would never be considered one of them. I’d go so far as to say that if Brent suggested that he dreamed about it as a justification for us doing anything, we’d try to get him help.

Yet such a stance stands in contrast to many historical examples. Among them, Constantine was empowered to conquer Rome by a dream and Sitting Bull shown the courage and tactics to defeat Custer at Little Big Horn.

What’s happened then for dreams to have declined so much in relative strategic value?

This is the question posed in The Oracle of Night, one of the more engaging books I read last year. Tracing an evolutionary path, it makes the case for paying attention to our dreams as useful signals of risk, opportunity, and probability. What are nightmares if not the brain scenario planning for tail events?

And after all, the things we think about and imagine while we are awake are hugely valuable to us. They inform everything we do. When we dream, it’s the same brain doing the same things, it’s just that the rest of us is asleep. Why are those ruminations worthless?

When I thought about it, I couldn’t answer that question satisfactorily (and figured I might as well take advantage of the arbitrage opportunity if my brain is willing to work overtime), so I followed the book’s advice and started keeping a dream journal. This takes the form of a reliable pen and notebook on my bedside table and when I wake up each morning I write down what I remember about what I dreamed.

Have I done something like move to San Francisco as a result? No, but it’s been interesting to look back at the problems my brain wrestles with at night and think about why and how they might inform what I do during the day.

— By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

You Can’t Find What You’re Not Looking For

I think everyone’s aware by now of the kerfuffle involving the Chinese spy balloon that went right over Permanent Equity’s HQ in Columbia, Missouri…

I think everyone’s aware by now of the kerfuffle involving the Chinese spy balloon that went right over Permanent Equity’s HQ in Columbia, Missouri, and was then shot down by fighter jets off the coast of South Carolina. One of the more interesting parts of the story to me is how we’re now seeing these types of aircrafts popping up more and more because NORAD “tweaked” our radar filters to start looking for small, slow-moving objects.

I mean, were we not doing this before? Do the people who keep us safe not remember that big things come in small packages and that the tortoise beat the hare?

I’m half kidding; I lived in DC when small envelopes of suspected anthrax terrorized the US Capitol.

But this latest experience is a powerful reminder that you can’t find what you’re not looking for.

One of our favorite questions to ask others is what keeps them up at night. And I can tell you that in my role one of the things that keeps me up at night is the idea of missing something in due diligence and investing our partners’ money for 27 years in a business that is not what we thought it was or with people who are not who we thought they were. We have lots of systems and processes in place to mitigate this risk, but it still is one. And we’re always paranoid about what we’re not looking for.

We can do phase ones, get background checks, reconcile numbers, etc. Heck, we just hired a certified fraud examiner. But unless you’re willing and able to be cynical and paranoid all of the time, it’s likely you are at some point going to assume something is harmless, let it slip by, and it will turn out to bite you. And that’s manageable, provided it doesn’t happen often, but recognize that it will and know how you might respond when it does.

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

ChatGPT is Bad at Math

The world continues to be both fascinated and frightened by the ChatGPT AI despite the fact that it’s not very numerate…

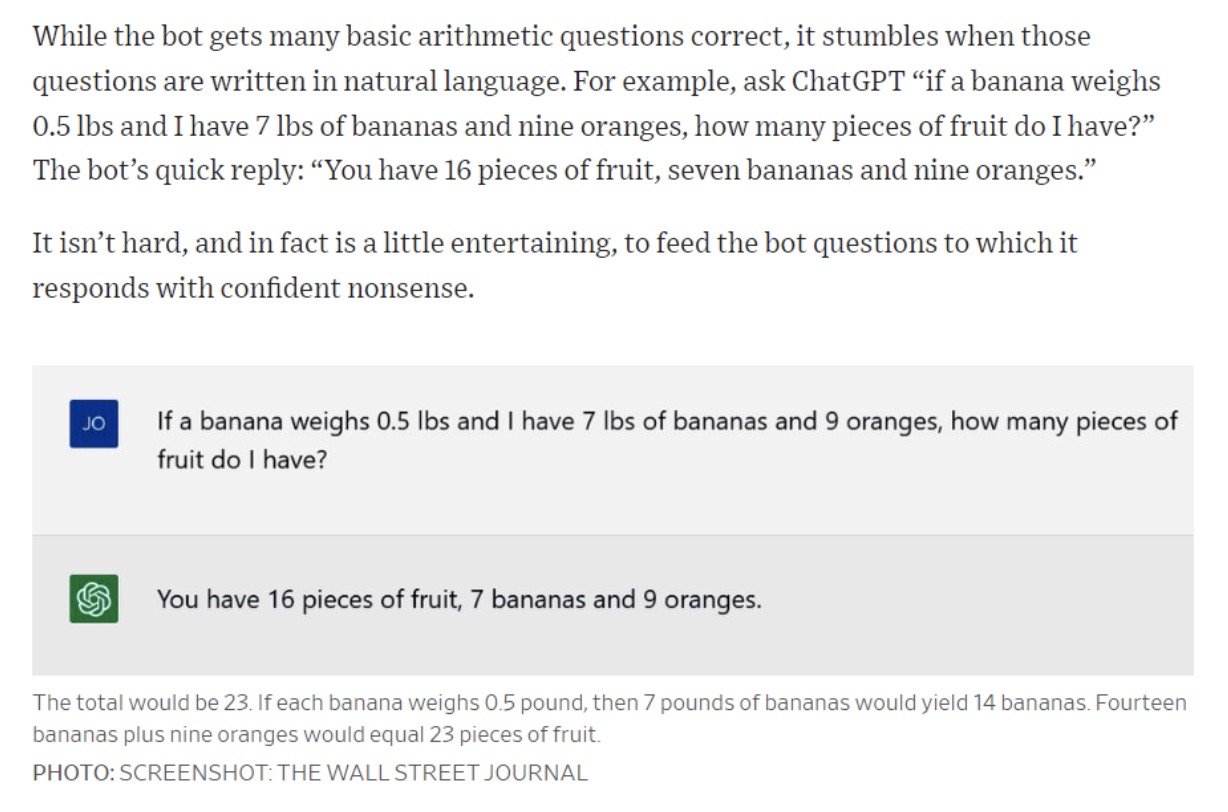

The world continues to be both fascinated and frightened by the ChatGPT AI despite the fact that it’s not very numerate:

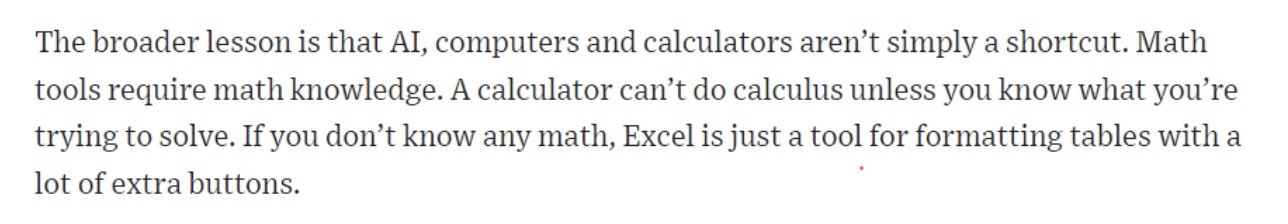

Yet maybe that’s the point:

And:

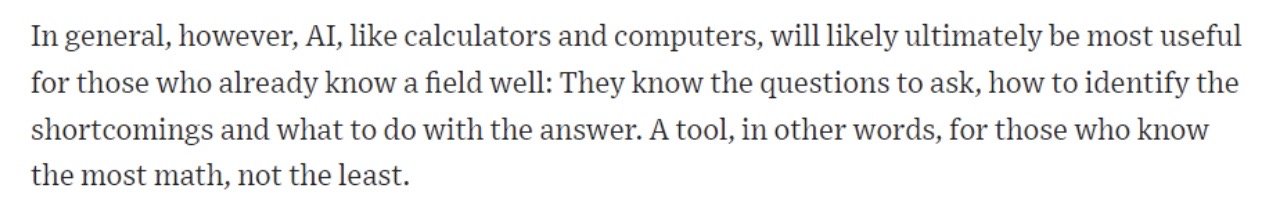

The universe of companies we typically see tend to be slow adopters of new technology despite having vast amounts of industry, product, and customer knowledge. Knowledge, in some ways, is an inhibitor of tool adoption because the new tool is not necessary for the company to do just fine given its knowledge advantage.

When we invested in our airplane parts business, for example, there were two guys (nearing retirement) who’d memorized tens of thousands of airplane parts numbers, knew what they were typically bought and sold for, and acquired millions of dollars worth of inventory every year based on that knowledge.

It was amazing but (as new investors) also terrifying.

When we asked if they ever thought about automating the process or writing a pricing algorithm, they laughed at us. They didn’t need to.

But one of the first things we did when we got involved was collect and structure that data so we could let computers train on the data and price parts for us. We thought it would make the business smarter, but also more prepared for when those guys retired. That technology has done that for us and then some.

The learning is that people with the most knowledge should be the early adopters of new tools even when it’s not obvious they need them yet. The reason is that if they aren’t, the tools will eventually level the playing field, but if they are, it’s in their hands that that new tool will be most powerful.

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

CIMple Truths

Look, we have empathy for the analysts at investment banks tasked with putting together lengthy decks about small private businesses (aka Confidential Information Memorandums or CIMs for those not in the know).

Look, we have empathy for the analysts at investment banks tasked with putting together lengthy decks about small private businesses (aka Confidential Information Memorandums or CIMs for those not in the know). Information is often incomplete or missing altogether, there are skeletons in the closet, and the people approving your work probably don’t appreciate how difficult it is to make a color pop.

That said, we occasionally see some things that make us scratch our heads. In no particular order…

Cutting off the numbers on an oddly specific date…

What happened in the last three weeks of the year? Don’t worry about it.

Puzzling celebrity pull quotes…

Hell yes you can, Billie Eilish.

Math that doesn’t quite add up…

Wait, what?

Showing really big numbers with wanton disregard for base rates.

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Your Downgrade is Not an Upgrade

When he was CEO of Amazon Jeff Bezos was famous for passing along emails from customers to staff when it was obvious the company had done something that wasn’t “customer-centric.”

When he was CEO of Amazon Jeff Bezos was famous for passing along emails from customers to staff when it was obvious the company had done something that wasn’t “customer-centric.” After all, every day is allegedly “Day One” at Amazon as it strives to be “the most customer-centric company” on Earth (and maybe the Galaxy if Blue Origin goes to plan).

It’s with that as background that I almost emailed new Amazon CEO Andy Jassy the other day when my daughter asked Alexa to play a song – like she had thousands of times before – only to have Alexa play a completely different song.

After a brief, frustrating interrogation it became clear that in order to regain the previous functionality of playing a song on demand, one had to now purchase an additional Amazon subscription.

The Wall Street Journal recently covered this story and apparently the Hanson family is not alone in feeling enmity towards the change. What’s more, I call BS on Amazon’s claim that the change was driven by “customer feedback.” That’s obvious corporate double-speak.

Instead, given the current economic climate and recent layoffs at the company, I suspect this is an attempt to put a short-term jolt into Amazon’s income statement. And while it may work, what’s remarkable is how un-Amazon-like such a move is. For most of its life as a company Amazon has been famously long-term, foregoing profits to reinvest in the business and build arguably the most loyal customer base in the world. Historically it’s been successful at passing through price increase after price increase on its Prime service because it’s always so visibly improving.

So this is notable. It’s the first time Amazon has degraded its service because, maybe, it feels like it hasn’t earned the right to increase prices. That’s a troubling sign and points to a business that’s being run by the numbers and not generating them.

— By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

The Lego Investor

One of the best articles I read recently was about this guy, Dr. Paul Janssen, who spent years building a model of Ohio Stadium (The Ohio Stadium) out of Legos.

One of the best articles I read recently was about this guy, Dr. Paul Janssen, who spent years building a model of Ohio Stadium (The Ohio Stadium) out of Legos.

There are a lot of threads to pull from that article, but what I want to know is: What is Dr. Janssen’s IRR?

Hitting secondary market sites like BrickLink and eBay, Janssen spots sets that he wants, then carves them up and sells off individual pieces he doesn't need — especially the little figures in many sets — to not only recover what he spent but to make money. He especially makes a killing by buying Harry Potter sets, keeping the pieces and bundling the Potterverse characters to sell to collectors. He'll sometimes clear out entire post-holiday inventories of stores, then wait a year (or two or three) before selling them online. It's the equivalent of buying all of Walgreens' clearance Valentine's Day stuff at 90% off, eating half of it, then selling the rest at full price next February.

"Paul figured out how to buy and sell patiently," Coifman says. "Before you knew it, he was building skyscrapers that were $5,000 worth of bricks. He was a rags to riches Lego buyer."

In fact, for most of the past 20 years, Janssen has had to file an annual tax return for the money he brings in, which has ranged from a few thousand dollars as high as mid-five figures. He is stockpiling a Lego warehouse while making money.

For the stadium, Janssen used all of his Lego economist skills. He drew up a massive diagram of what he would need using photos — some from aerial images, some he took himself at home games. He needed massive amounts of basic blocks, which he mostly could pull from his already existing inventory.

But then he ran into a common problem for Lego "purists," the term he and other builders use for those who refuse to cut, glue or paint blocks. Everything he builds must naturally exist in a set, with no adaptations allowed. For Ohio Stadium, he needed 60 to 70 curved arches for the top of the stadium, the kind that isn't produced often by Lego.

He finally discovered a set sold only in Europe in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Each set included two arches that looked perfect for his stadium project, so he methodically began placing orders from sellers all over the world. He'd buy one or two at a time, chipping away at the 30 to 35 sets he needed. After months of hunting and gathering, Janssen finally had every arch he needed. Then he bundled up the other bricks and sold them online, basically breaking even by the time he was done.

Smarts. Patience. Painstaking research. Some luck. Price discipline. A willingness to look stupid.

That’s how you do it.

— By Tim Hanson

Wondering what to expect from the SMB market in the coming year?

Try our latest publication, “How to Sell Your Business in 2023.”

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

If You’re Going to Invest in Ponzi Schemes, Diversify

We had a joke at my old office that Ponzi Schemes would be a great asset class if only someone could appropriately manage the duration risk.

We had a joke at my old office that Ponzi Schemes would be a great asset class if only someone could appropriately manage the duration risk. In other words, the optimal Ponzi Scheme would be a Ponzi Scheme of Ponzi Schemes. Because while every individual Ponzi Scheme is eventually going to be found out, if one could theoretically ladder them together, there’s very little chance that they would all be found out at once, which would smooth the return stream for a very long period of time. Theoretically.

But before the SEC comes knocking, know that I am not doing this. Moreover, know that I am not suggesting FTX or any of the other speculative recent blow-ups were or were not Ponzi Schemes. (History will be the judge.) Rather, what I’m suggesting is that you can (again, theoretically) take unimaginably stupid risks (like investing in nothing but a portfolio of Ponzi Schemes) as long as you are properly allocated.

Look, everyone is going to get duped. I’ve invested in companies that I now know were probably fraudulent. I’ve been stolen from. I’ve trusted people I shouldn’t have. I’m still here. The reason is I never put everything on the line.

The heartbreaking thing about FTX and others such as Enron was that many innocent people did. The Wall Street Journal reported that “Some employees kept their life savings on FTX” because they “trusted that everything was fine.” This is a problem. You don’t invest in your employer let alone custody your assets with it because if something happens everything is gone.

I get made fun of around the office because I like to find “idiosyncratic assets” and “uncorrelated return streams”. In fact, I’m not allowed to use those words around real people lest I get punched in the face. But there’s method to the madness.

I truly believe that volatility is your friend. It’s only dangerous if you can’t survive it. It’s only when the game doesn’t end on your terms that you lose.

The corollary to this is that correlation is the most dangerous force in the universe. But note that correlation is not concentration. I bet (theoretically) that you could even be concentrated in Ponzi Schemes as long as they wouldn’t all collapse at the same time.

— By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Coffee, a Strong Dollar, and the Reverse Pareto

Our joke with investors is that the biggest risk to our ability to execute our investment strategy is cholesterol.

Our joke with investors is that the biggest risk to our ability to execute our investment strategy is cholesterol. So it wasn’t a surprise when Brent handed me a copy of Unreasonable Hospitality – Will Guidara’s recounting of how Eleven Madison Park became the best restaurant in the world – and said it was the best book he’d read in some time. I figured he’d been focused on the food, but what, he asked, does unreasonable hospitality look and feel like in the investing industry?

I’ll leave the answer to that question for another time (or email me back if you have opinions)...

Today’s focus is on the very average cup of filtered coffee Will writes about that he sipped at the end of his first dinner at Per Se. If you don’t know Per Se, it’s the restaurant famed chef Thomas Keller opened in NYC in 2004. Guidara describes the experience as “spectacular” and that “the attention to nearly every invisible detail” filled him with awe.

Nearly, he writes, because of that cup of coffee. It stood out because it was “just okay” when everything else had been so “perfect perfect.”

Guidara goes on to write how that experience inspired him to create an incredible coffee program at his restaurant, but what’s interesting to me is how that small detail marred the overall experience. Because it wasn’t a small detail that Per Se had gotten wrong. Rather, it was a small detail the restaurant hadn’t considered carefully.

We all know about the Pareto principle, which is the idea that 80% of results come from 20% of causes. If you get the big, important things right, in other words, then the outcomes take care of themselves. But Per Se’s cup of coffee is an exception to this rule. It’s evidence of the reverse pareto.

I don’t know if the reverse pareto is actually a thing, but for me it’s the idea that if you don’t carefully consider all of the forces that might influence your outcomes, you might be undone by something you were neither right nor wrong about, but just that you hadn’t tried to control for. Per Se didn’t make a bad cup of coffee. Instead they took it for granted that coffee was coffee.

Back when I was investing in emerging markets we tended to buy and sell stocks in local currency on local exchanges. If we wanted to buy an Indonesian stock, for example, we’d turn dollars into rupiah and make the trade in Jakarta. And when we did that we thought we were making a decision about the merits of that Indonesian company. But what we didn’t fully appreciate is that we were also making a decision about the merits of the Indonesian rupiah.

Of course we knew about currency risk and the fact that currencies strengthen and weaken over time, but our thought was we were long-term investors and that we shouldn’t hedge currencies because hedging is expensive and the exposures would all even out eventually. In hindsight, that was incredibly naive. What ended up happening is that the dollar strengthened against almost every foreign currency for years and years and years, creating a massive headwind for our portfolio. And even though our stock picks were beating their benchmarks in local currencies, our fund was losing to its yardstick in dollar terms – all because we hadn’t had a strong opinion about currency.

What’s the point? Being wrong about something sucks, but we are all wrong from time to time and when we get something wrong it’s frustrating, but fair, to take our medicine. What kills is when something you could have gotten right, but didn’t really bother thinking too much about because you assumed it would take care of itself, ends up being the undoing of your enterprise.

Incidentally this is why, at Permanent Equity, we don’t mess around with our coffee. (Shoutout James, Taylor, and Danny Coffeepot.)

— By Tim Hanson