Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions delivered to your inbox.

Growth and Feedback Loops

One of our portfolio companies recently completed our second tack-on acquisition, and we are hunting for more. That hunting, however, is not broadly across our entire portfolio, but only at companies for which tack-ons make sense. The reason that’s so is because growth is risk and if we try to do a tack-on at a company that is not prepared for it, then the complexities associated with finding, evaluating, closing, and then integrating an entirely new, different, and potentially messier operation might derail the core business.

In recognition of that, we developed a simple checklist to help us gauge when we might pursue tack-on acquisitions on behalf of one of our portfolio companies. For us, the company needs to have:

Demonstrated stable business performance;

While generating timely and accurate financial statements;

With trusted leadership in place that is likely to remain in place; and

Resources available to oversee integration.

Our view is that absent these characteristics, a business that makes a tack-on acquisition is:

Unlikely to know what to do with it;

Unable to manage it; and

Without any idea how it’s going (or, worse, liable to have hallucinations).

And that, for us, is a recipe for disaster.

Recently, we’ve started putting the many business models that exist in this world into two buckets: fast feedback loop and slow feedback loop, with a variety of factors determining the pace of the feedback loop of a business. In other words, if you make, sell, get paid for, and watch your customer consume your product all on the same day, that’s a fast feedback loop. If that happens over a period of years, on the other hand, that’s a slow feedback loop.

Our experience is that slow feedback loop business models are dangerous because you can’t have a precise idea of how you’re doing at any given point in time. You know how you’ve done and how you might expect to do in the future, but things could go off the rails at any time without you being aware that they have for quite a while.

To bring this back to tack-on investments, the point of our checklist is to make sure that any of our businesses that do one have the conditions in place to make sure that the feedback we get on the deal is fast. Because if it’s not working we want to know that as soon as possible in order to right the course and if it is, we want to know that too so we can try to do another one.

Because while organic growth is great, inorganic growth, done right, is a cheat code.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Be Kind, Not Nice

Maybe it’s semantics, but recently around the office we’ve been talking about the difference between being low-performance nice and high-performance kind. This came up the other day because a CEO we know reached out about one of her senior employees. This person, who has been struggling in his role for some time, expressed frustration about having not received a compensation increase for some time. What, he asked the CEO, did he need to be doing differently?

The CEO sought our advice because, while this was not a critical employee, it was an important one. Further, her assessment of the reason for his struggles was more fit than attitude or skill, but unfortunately the business did not have a role to offer that might be a better one. So if she told him the unvarnished truth, she was not only worried that he might leave, but that in this tight labor market, he would prove difficult to replace. Might it be better for everyone, she wondered, if she said she thought everything was fine and encouraged him to just keep working hard?

Given that context, what we’ve been talking about around the office is that the latter seems like the low-performance nice thing to do. It doesn’t rock the boat, it closes down the conversation, and it doesn’t make anyone uncomfortable. And the fact that it doesn’t make anyone uncomfortable – neither the CEO nor the employee – is a key point. It’s relatively easy to be nice, and being nice enables one to be done with a hard conversation. In other words, being nice is about protecting you to the disadvantage of the other.

If something is easy and conclusive, of course, it probably means it is also lazy and settling (except for no-brainers). Hence the low-performance part. Because those aren’t the characteristics of a good business or, more importantly, a good relationship.

So if that’s the low-performance nice thing to do, then what’s the high-performance kind thing to do?

Now, nice and kind are often used interchangeably and certainly what they have in common is that a person who is those things is polite, careful with words, and cares that the people they are interacting with have a positive experience. With that as a given, the high-performance kind thing to do here would seem to be to explain to the employee the situation he finds himself in that is in some ways through no fault of his own. And then to take time to figure out where the employee sees himself in the future and ideate paths forward that might help him get there. Another high-performance kind thing to do would be to offer support, but not subsidy.

This, of course, is harder than being low-performance nice. Not only does it take more time and thought, but if the conversation doesn’t go well it also potentially leaves the CEO in the lurch. Yet if it goes well (and why wouldn’t it if you truly have one’s best interests in mind?), everyone ends up better off. Put another way, kind is about helping the other, which should end up being better for both of you because it’s always the right thing to do to help people get where they want to go (just don’t ask me about the time some West Virginia fans asked me how to navigate the DC Metro after their team had defeated Georgetown in basketball).

So be kind, not nice, and have a great weekend (and sorry to those West Virginia fans who got on the wrong train).

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Average Deals

Someone asked me about Permanent Equity’s average deal the other day, so I pulled the numbers. On average, I reported back, when we make an investment we buy 75% of a company, write a $20M check, and pay six times beer money.

But, I said, you may want to be careful with how you use this information because we don’t own 75% of any company and have never written a $20M check nor paid six times beer money. Instead, we own anywhere from 51% to 100% of our portfolio companies, have stroked checks ranging from $5M to $68M, and paid (leaving aside the nuance as to how some of these investments were structured) as little as two and as much as 12 times beer money.

Now, when I tell people about this deviant behavior, the reactions are not down the middle either. In fact, one potential investor declined to continue chatting with me, saying “your deals seem funky and capital deployed is too intermittent.”

Okay, then.

But this particular investor said, “That’s great. The fact that you all have done such a wide variety of deals shows that you’re taking advantage of the flexibility of your fund structure and lends credibility to your claim that you’re always trying to do things that make sense.”

Exactly.

See, no two deals are alike for us and there is no average deal. That’s because we view sellers of businesses as our customers and our product as capital. And since money can easily become a commodity where the only better is more, we try to offer our customers differentiated and personalized products that best achieve what they are trying to accomplish. In some cases, yes, that’s money, but in others it can be things like partnership, certainty, legacy, or peace of mind (or some combination of all of the above). That doesn’t mean we win every deal, of course, but we find that since our offers tend to stand out, they usually garner presentation and at least some consideration.

And since nothing gets done without first being considered, here’s to never being average.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

I’m Gonna Finish this White Paper

Something I first read a long time ago, but that took a while to understand and appreciate was this special feature from the June 2000 Bank for International Settlements Quarterly Review. Called “Evaluating changes in correlations during periods of high market volatility,” it makes the case, using math, that when things become more volatile, they also become more correlated.

Now, if you’re among the legions of people more intuitively numerate than I am, you might be saying, “No duh.” But for me this was not intuitive. That’s because it seems like one way to think about volatility would be as difference. For example, if lots of things are zigging and zagging all the time, it seems like it should be the case that all of that zigging and zagging would be more random and therefore less correlated.

But another (and the right) way to think about volatility is as magnitude. In other words, something that’s volatile isn’t necessarily zigging and zagging a lot, but rather has the potential for explosive zigs and catastrophic zags. And as the math in that paper shows, while there can be a lot of relative difference between a lot of events in a clustered distribution, extreme events are fewer and a lot more alike relatively speaking precisely because they’re extreme and so they are much more highly correlated.

This is a problem for business and investing because Modern Portfolio Theory posits that you can earn better returns with less risk by doing things that are uncorrelated. But if it’s true that things become more correlated when they start going really badly, then the benefits of being diversified are reduced at precisely the time you need them the most.

And this is a reality that has proved to be true during significant market dislocations.

This National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, “Long-Term Global Market Correlations,” was published in November 2001, just as the bursting of the tech bubble and 9/11 terrorist attacks were wreaking havoc on global markets. It remarked that “the diversification benefits to global investing are not constant,” that “diversification potential today is very low compared to the rest of capital market history,” and that “periods of poor market performance, most notably the Great Depression, were associated with high correlations, rather than low correlations.” Global correlations increased again with the 2009 financial crisis, and during Covid everything went way down then way up together.

In other words, it’s clear that when people panic, they’re likely to panic about everything all at once.

And while there is less academic research into how this propensity manifests itself in small operating businesses, I can tell you from experience that when something starts to go poorly at a small operating business, a lot more is likely to go poorly alongside it. A business that loses a bunch of money on a project, for example, might see performance suffer at other projects as it repurposes its best people to deal with the crisis. Then its controller, stressed out by the situation, might decide to retire a year earlier than expected, leaving a massive hole on the leadership team right when accurate numbers are most important. And seeing deteriorating prospects and a lack of appetite for growth, a star salesperson might then leave for a competitor. Heck, it’s when morale is low that office supplies even start to disappear.

When it rains, as they say, it pours.

So if the lesson is that the world is more correlated than we think, an implication is that we can’t engineer our way to stability when constructing an investment portfolio or building a business. Instead, we have to accept that there will be instability and that when it happens, there will be a lot of this at once. The two ways to handle this are (1) temperament, i.e., know ahead of time what you’ll need to do to keep your cool and (2) structure, i.e., your agreements with others and liquidity requirements can never turn you into a forced actor.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Skateboarding Non-Competes

AThe thing I miss most about living in the city is skateboarding to work. See, because if you live one mile or so from your office (and not on a gravel driveway in rural Missouri), a skateboard is the ideal form of transportation. That’s because:

You get where you’re going faster that if you were running or walking; but

You don’t sweat through your work clothes; and

You can keep that mode of transportation under your desk; so

You can commute home quickly in the evening even if traffic is backed up into the parking garage (true story).

But the problem with skateboarding to work back when I lived in Alexandria, VA, was that it was illegal. Skateboards were not allowed on the roads, nor in the bike lanes, nor on the sidewalks, which made for a bit of a kerfuffle about where they were allowed. And while very few police officers enforced those limitations, few is not zero, and so therefore I had a number of awkward encounters with badged men with strong opinions.

Thankfully, nothing ever escalated to the level of prison. But I mention this all here in reference to the recent FTC decision to nullify and ban non-compete agreements.

Bear with me…

I wrote that one way I’m inspired to write these missives is by talking through things with my son on the way to school in the morning. And so this came up the other day when we were listening to NPR and Morning Edition reported on this story in between reporting on how abortion restrictions are contributing to global warming (I kid, I kid). He was interested in the issue (non-competes) and knew that it had relevance to me and asked what I thought about it. I said something like, “Most non-competes are unenforceable anyway, but that said I’m all for free markets, but that also said, I’m also for contracts.”

I get, of course, that the idea here is that some number of these so-called non-competes have been thrust on people who don’t understand what they agreed to and also may not have the firepower to litigate them (and therefore are already unenforceable!). But provided there is thoughtful negotiation between informed parties, what about leaving us negotiators alone? Because I didn’t see anything in the FTC’s ruling about reducing compensation or severance for eliminating the non-compete even though those things would have been agreed to right around the same time. And if that’s true, this would be a long-term drag on wages and business valuations (particularly for those whose main asset is intellectual property) even as it might be a near-term election year talking point win.

Imagine that.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

You’re Not Obsolete

Emily texted me the other day and said “Your next Unqualified Opinion should be about how just because you say something doesn’t make it true.” Her beef was with an email we had received from someone who was clearly integral to the success of her business saying that she wasn’t integral to the success of her business because all she did was drive strategy (which only happened a few times a year), review the financials and set goals (which only happened monthly), and collect overdue AR (which only happened weekly).

So not integral!

The statement is absurd on its face, but the reasoning was that none of these activities happened daily and therefore were not critical to day-to-day operations. And while it’s true that none of these things happened daily, that reasoning ignored the fact that these more intermittent activities are what enabled critical daily activities to occur.

When we pointed that out, we were met with frustration. This was not only because we were disagreeing (on the merits!), but also because I think us pointing that out forced this person to come to terms with the fact that she had not achieved an important goal of hers, which was to have made herself obsolete.

Look, we should all be endeavoring to make ourselves obsolete. Our jobs, our families, and the world will one day have to move on without us and we should do what we can while we are present to make sure that that inevitable transition is as seamless as possible.

Yet even if you recognize that and work hard to achieve it, a true fact is that unless you are entirely absent, you are never as obsolete as you might tell others or lead yourself to believe. Case in point, we invested in a business where a clear succession plan was in place and there was universal agreement that the number two was ready to take over. Then the CEO was diagnosed with cancer. A few days later he went into the hospital and never came out.

While the business at that moment was the least of our concerns, when we and everyone else got back to focusing on the business, we believed it to be in good hands. Many moons later, and only after the numbers had worsened, we figured out that while the business was in caring hands, it wasn’t necessarily in adept hands. By losing that CEO, we had lost an important driver of quality control. In other words, even though the CEO wasn’t necessarily doing much, he was, by virtue of sitting in his seat and having the potential to do something, causing others to work smarter and make better decisions.

I told this story to the “not integral” woman we were talking to and also said “Hey, look, this may be my own problem that I have scar tissue.”

But!

Scars are scars for a reason, and you should never want to or do something again that gave you one. She looked like she agreed, but didn’t, but also did, but also didn’t want to admit it. The resolution is that we’d both think about it and revert.

The heartwarming side of this story is that as long as you’re around, you’re at least not obsolete and probably more likely incredibly important. The more frustrating flip side is that you and others, even if you’re being intellectually honest, probably don’t fully appreciate that.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

What You Think is Worth Reading

After I made my recent book recommendations, I had more than a few people (since I asked you to) send in their own. Thank you! I’m always on the lookout for new tomes and now I have some things to take to the beach with me this summer. In case you’re also deciding what to read next, here’s what some others are recommending (with some reasons why)…

Jon: Thinking in Bets by Annie Duke

“Thinking of decisions in terms of bets and odds has been a very useful framework for me, and the book has a lot of overlap with concepts like Bayes and position sizing.”

Justin: Calculated Risks by Gerd Gigerenzer

“The book really helps with the logic (with great visuals) on how to think about Bayes’ theorem, base rates, and how to update. A good read for investing, but more importantly a great book to help you think about the numbers you see in life.”

Joe: Liar’s Poker by Michael Lewis

“Guys in suits often aren’t as knowledgeable and/or smart as they appear.”

Johnny: Boss Life by Paul Downs

“Nothing gave me a better appreciation of the daily battle that is SMB ownership.”

Matt: Great Mental Models by Shane Parrish

“Improving the way one thinks is likely the best compounding investment anyone could ever make.”

Emily: Glass House: The 1% Economy and the Shattering of the All-American Town

“The author draws some pretty extreme conclusions (basically blaming private equity transactions for the opioid epidemic in Ohio), but his research on the actual cycle of deals is thorough and well told. This book will probably never leave my mind.”

Michael: Capital Returns by Edward Chancellor

“The boom and bust told through the investor letters of Marathon Capital.”

Milo: Investing: The Last Liberal Art by Robert Hagstrom

“Big ideas in multidisciplinary domains with parallels to investing.”

Mark: The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making by Scott Plous

“A highly concentrated walkthrough of the biases that drive our everyday decision-making and how we can fight against them.”

Oh, and a lot of people think you should read The Psychology of Money by some Morgan Housel guy. Whatever. Have a great weekend.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Mushrooms!

We’re in the midst of mushroom hunting season here in mid-Missouri, which means that the crazy guy with the knife wearing the Capital Camp hat (May 21!) walking slowly through the woods out by the river at six in the morning is me. Mushroom hunting wasn’t anything I’d done before we moved to mid-Missouri, but I picked it up as a hobby as part of the whole “if we were going to move to Missouri, we were going to move to Missouri” thing. Plus, one of our neighbors was pretty sure I could never find as many as he does and, well, I do still have a bit of a competitive streak in me.

Anyway, Holly, after stumbling across a cryptic post on my X nee Twitter page, asked me about hunting mushrooms the other day and how I did it. Suffice it to say that there isn’t a lot you can learn from others about hunting mushrooms. That’s because people are secretive about their spots and techniques since the season is short, supply is limited, and the little guys are both valuable and delicious. My aforementioned neighbor, for example, after challenging me, had no interest in showing me the ropes (and I don’t blame him).

So five years ago I googled the basics and then spent a lot of hours walking slowly through the woods near my house finding very few (14 to be exact…I have a spreadsheet).

Fast-forward to today and I found many more than that in my first hour of hunting this season. Why? Because now I know where to look!

See, morels have a tendency to spring up in the same areas as they have in the past. Not always, of course, but your probability of finding one is much higher if you are looking in a place where you found one before than if you’re looking in a place where you haven’t. And every year I’ve looked, I’ve found at least one new place to look, which means that five years into the hobby I now have more than a few “spots” (shoutout compounding).

Because every time I go out, I don’t just go to the spots I know will yield. Instead, I also set aside at least 30 minutes (depending on how much time I have) to look in spots I’ve never looked in before, in spots I’ve looked in before because they seem like they should be promising from a moisture/soil/sun/leaf cover perspective, but that haven’t previously yielded anything, and in spots where I may have once seen a crazy person slowly walking through the woods in April. The reason being “just in case” and also because I always want to be adding to my spots in case one of my spots goes away (which happened a few years ago when a particularly good one flooded over).

And when I explained this, someone who was listening in (I can’t remember who) said, “Aha! 20% time!”

If you don’t recall, 20% Time is Google’s (perhaps apocryphal) policy that full-time Googlers spend 20% of their day doing something that isn’t proven, but is instead high potential. To apply this to small business, I previously recommended to “Keep a list of everything your business might do to grow…but force rank them based on potential and only tackle one or two at a time” and to “watch competitors…like a hawk and be shameless about trying things they are doing that might be working.”

All of this is to say that I was subconsciously treating my hobby like it was one of our businesses, and when I realized that, I realized I might be a little sick.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

The White Paper Work Continues

Diversification can get a bad rap in the investing community as “diworsification,” which is to say that if you are spreading your bets too thin, you’re not mathematically making any bets at all. Of course, a mitigating factor here when applying this framework to small, private companies is that these companies tend to be volatile and, as I’ve said before, can be at all times a few consecutive bad months away from a crisis. What that means is that if you are trying to build a compelling long-term return stream in our space, you need to be cognizant of aggregating highly disparate assets. Further, your odds of diworsifying among small, private companies is difficult because you can’t practically go out and acquire 100 or more all at once like you can in the public market, so the risk to be aware of is concentration, particularly if it’s inadvertent.

And that’s the twist re: diversification among small, private companies. Ones that look different can actually be quite similar and ones that look similar can actually behave very differently. So what makes a small, private company a disparate asset?

When it comes to public companies, for example, accepted vectors for diversity include size (even though almost all public companies in the overall scheme of things would be considered pretty big), industry, geography, and growth profile/valuation. Among small private companies, however, size doesn’t really apply, since none are big enough to not be fragile and nor, for the most part, does growth profile/valuation. That’s because valuations tend to cluster around the average and also because, as we like to stay around these parts, no business stays small on purpose, so the growth of any mature small business is definitionally being blocked by something.

That leaves industry and geography, which both apply and should often be considered in tandem, though on a more refined scale (e.g., it’s not US versus EMEA, but the Sun Belt versus the Northeast). For example, a pool company in Arizona makes a lot less margin on service than one in the Northeast because in geographies where it freezes and thaws, there is more price insensitive seasonal pool opening and closing revenue. And a fence company in a geography with soft soil will have better economics than one operating in rocky soil because of the throughput on putting up posts.

So if you’re building a portfolio of small, private business, here are some other vectors to consider:

Seasonality: A fireworks distributor will generate a much more reliable stream of cash flows when paired with a Christmas ornament manufacturer than it will with a pool toys manufacturer.

Business model: A service company that gets paid upfront will generate a much more reliable stream of cash flows than a construction business that has to try to collect 20% retainage.

Weather: We didn’t realize until it happened how much a rainy month in the Southwest would impact our pool, fence, and waterproofing businesses all at the same time.

Deal structure: If all of your deals have earnouts, it might be a long-time before you generate a reliable stream of cash flows, so if you do a deal with an earnout, you might complement it with a deal that includes a preferred return.

People: Your portfolio is significantly riskier if all of your operators want to retire within three years than if they don’t.

The point is that if you’re building a portfolio of small, private businesses then you’ll want to be as highly diversified as you can be, but also that what makes for diversification in this space can be incredibly idiosyncratic. So be aware of what your exposures are and aren’t with the goal of turning inevitable individual business volatility into a more reliable blended return stream.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Space Junk

One of the craziest stories I’ve been following recently awaiting resolution was that of the Florida man whose house got bombed by NASA. Because way back in March 2021 the International Space Station decided to throw out 5,800 pounds of old batteries, expecting them to burn up in Earth’s atmosphere and disappear forever. But 1.6 pounds sneaked through, blowing a hole in Alejandro Otero’s roof in March 2024 and crashing through two floors while almost decapitating his son.

Whoops.

Commenting on the fact that the rocket scientists didn’t quite get the math right on this one, NASA wrote:

The International Space Station will perform a detailed investigation of the jettison and re-entry analysis to determine the cause of the debris survival and to update modeling and analysis, as needed. NASA specialists use engineering models to estimate how objects heat up and break apart during atmospheric re-entry. These models require detailed input parameters and are regularly updated when debris is found to have survived atmospheric re-entry to the ground.

NASA remains committed to responsibly operating in low Earth orbit, and mitigating as much risk as possible to protect people of Earth when space hardware must be released.

Comforting, no?

I wrote a while back about the spreadsheet that presumably exists somewhere where if you change the value of one cell (the one that calculates estimated future viewing patterns of Netflix content and therefore the rate at which the cost of that content is amortized), you could double Netflix’s profit or cut it in half. Well, apparently there’s also a spreadsheet somewhere where if you change the value of one cell (the one that calculates how much various metals heat up and break apart during re-entry), it might get us all annihilated by falling space debris.

All things considered, Mr. Otero seems to have dealt with this manifestation of what I call “Are you effing kidding me?!” risk in a remarkably calm manner. He’s waited for NASA to confirm its findings and is asking them to “resolve the damages” (though I have no idea what court has jurisdiction over space releases and/or whether or not anyone could prove that NASA was negligent here). But if they don’t “resolve the damages,” well, are you effing kidding me?

Here are the takeaways:

Risky actions can take a long time to materialize into tangible consequences. While federal law may have a 5-year statute of limitations, the real world can punish you whenever it wants, so reserve accordingly.

Exogenous factors outside of our control are conspiring against us all the time, even up in low Earth orbit. You may not have time to worry about space junk, but you need to be prepared for space junk.

Oh, and your model is probably wrong.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Hair Is Opportunity

We have a joke around the office that we’re in the business of shaving hair. This is in recognition of the fact that small- and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) often come with lots of hair on them in many forms. That can include sloppy accounting, unresolved personnel matters, customer and/or supplier concentration, and even compliance with laws and regulations that is, shall we say, in the gray area. And of course this hair is what can make a business hard to transfer and even uninvestable.

But!

One way to create significant value is to remediate these issues over time i.e., shave the hair. That’s because in doing so, while you might or might not improve the performance of the business, you’re making it more investable. That increases the size of the pool of potential future buyers, making the business more valuable.

In other words, the less hair, the higher the multiple.

To wit, we saw a business recently that had botched an acquisition a few years ago and in the course of trying to integrate it had lost and was still losing quite a bit of money. Further, it had been through several rounds of layoffs, revalued inventory, written off assets, and recategorized expenses. The numbers were a mess.

That’s hair.

And while it’s normally not a good thing to lose money with that much hair, what was oddly impressive about this situation was that the core business had been able to fund those losses for so long. What that meant is that the core business might actually be a good one. Or, at the very least, that it could afford to pay for its shave.

So I said to Holly, “Hey, let’s reach out and see what the story is here. While we’d normally not be interested in a business with so much hair, this hair seems shave-able. And if we can shave the hair, we should do okay.” And Holly, after giving me a funny look, agreed.

The key to shaving hair, though, is not just knowing what the hair is, but also figuring out ahead of time that you can shave it. And there are two keys to that:

The business is generating enough cash to self-finance its shave.

The people at the business won’t resist or sabotage being shaved.

But if either one of those things isn’t the case, well, you might as well just start calling the business Cousin Itt.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

You All Do a Good Job

I should have seen it coming…

Prompted by me to tell me that I do a good job, you all responded with a whole lot of emails telling me I do just that. Thank you for making my day. It turns out there is no such thing as too many kind and thoughtful emails. After all, no one puts something out in the world without wanting a genuine response, so good job on that.

Of all of the responses I received, two stuck out for their clarity of thought and so I thought I would pass them along. One, from Casey, said this:

As a people-pleaser, I often catch myself writing “Sorry to clog your inbox” (I’ve maybe even said it to you). As with many things, I’ve settled on it coming down to scarcity versus abundance. If I feel like I’m clogging an inbox because I’m looking for attention or some other ulterior motive, that’s scarcity, and I rethink whether I want to send. If I’m sending because I appreciate what they said or it’s something else genuine, that’s from abundance and I send. Not a hard and fast rule, but it’s been helpful.

Lance, striking a similar tone, said:

I’ve contemplated this a lot and have arrived at erring on the side of over communicating. Email is one dimensional communication so acknowledgment of receipt or saying a quick “Thank you” is affirming and closes the loop.

That last bit in particular resonated with me because one of the most infuriating things that happens in my life these days is when I say something to my kids and they don’t respond. While I’d certainly prefer a positive response, I could handle a negative response, but what’s infuriating is the lack of response. It leaves me wondering if they heard me, care, and what they’re thinking.

C’mon guys!

Because maybe that’s what we’re all reliably looking for in this world: acknowledgment. Have a great weekend.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

How to Test

One of the scarier and more difficult, though unfortunately necessary, parts of operating a business is testing the validity of new ideas. That’s because doing so risks time and capital and can be disruptive to your core business, but also if you don’t do it, your core business risks stultifying and being competed away.

Remember, either you or the world is always moving on.

To that end, we keep a prioritized list of new ideas for each of our businesses and try to be tackling at least one (and ideally the one with the most potential bang for the buck) at all times. The question is how best to do that?

Because I’m the one who keeps a very close eye on our capital stack, I’m generally a fan of incremental testing. This approach is born out of the lean startup/minimum viable product schools of thought, which is to say that if you have a hypothesis about a new initiative, the right way to go after it is to start small, iterate as you go, and feed it with more capital only as it proves itself out.

To that end, our COO Mark is constantly advising our businesses to test new things so long as those tests are (1) measurable and (2) above the water line. What above the water line means is that if the test fails, it’s not catastrophic to the business i.e., punching a hole in the side of a boat is not as bad as punching a hole in the bottom. And if you do find a win, then work on scaling it.

Of course, a catch-22 here is that if you have a big strategic idea and you’re only willing to start small and test incrementally, you may never get around to actually testing that entire big strategic idea. To wit, we have a retail business that is interested in assessing the opportunity of having a brick & mortar location. (And before you say that’s stupid the economics of selling online are way better, a true fact is that building a durable consumer brand requires selling through multiple channels.)

Now, they did the work and identified an ideal spot where we could open a store that would benefit from the right kind of foot traffic, and that could be staffed with people who already knew the brand well and stocked with inventory that could quickly be repurposed if we got indicators that the test wasn’t going well. It was a more significant initial capital outlay than I’d typically greenlight, but when we modeled it out, the returns from getting good data on how to open physical locations was very much worth it.

Unfortunately, the landlord came back and said we couldn’t have that space, but that we could have one that was not entirely dissimilar and also quite a bit cheaper. It wouldn’t benefit from the right kind of foot traffic, but would allow for the risk mitigation pieces on the staffing and inventory side.

As we thought about that, though it was less expensive, we decided that wasn’t a test we wanted to run. The reason was it wasn’t a good location, and if we ran the test and it failed, even if it didn’t cost us much in dollars, the cost of getting a false negative on a big strategic idea might in the long run turn out to be really expensive.

In other words, there is a fine line between the lean startup/minimum viable product/incremental approach and half-assing something. Further, it’s important to know the difference between the two when thinking about how best to test a hypothesis about your business. So in designing any kind of test, resource it sufficiently such that the conclusions you ultimately draw from it are meaningful. That may cost more upfront, but the cost of believing something to be true that isn’t is likely to be significant.

— Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Still Working on that White Paper

When it comes to thinking about how much capital to put behind an individual investment, one universal truth and three considerations apply. The universal truth is that anything can go to zero, so never invest an amount that if that amount did go to zero, it would prevent you from making additional investments. That specific amount will be different for different actors, but one way to know that you haven’t sized your bets too big is if you always live to fight another day.

And while that advice can help one avoid catastrophic blow-ups (which is something we should all strive to avoid), a bigger challenge when it comes to generating above-average long-term return streams is betting too small. That’s because the more bets you make, the more likely you are to achieve average results, which are then likely to become below average over time due to the increasing frictional costs of trying to keep up with so many bets at once. Ergo the three considerations:

1. How big can this bet get if it goes well?

2. If this bet goes well, what is the net impact on returns if everything else in the portfolio doesn’t go well?

3. If this bet goes poorly, what is the net impact on returns if everything else in the portfolio does fine?

Asking and answering these three questions can help size the opportunity and scope the influence on the rest of the portfolio. The reason that’s important is because you want to be thoughtful about not making investments that are too small to matter, but also avoid making investments that are so big nothing else matters.

For example, one of the smallest investments in our Permanent Equity portfolio is a 3% position. Now, it’s expected to punch above its weight this year and contribute 4% of our total return, but run the numbers and that’s only 73 basis points of that return. So a fair question to ask is: Was it worth it to make and now maintain an investment that contributes less than 1% to our returns and that would still be relatively inconsequential in the scheme of things if it only doubles or triples?

Indeed, we asked that very question at the time we made this investment and our answer was yes because the total addressable market for this business is significant and the operating leverage inherent in the model meaningful, so we thought it had multiples more potential. This doesn’t mean it will achieve that potential, but by virtue of having it, this is a small position size that’s worth it. To put it the context of the considerations:

1. If this bet goes well, it could grow into a 10% to 20% position.

2.As a 10% to 20% position, this bet could be a meaningful positive contributor and make up for one or two bad bets.

3.If this bet goes poorly, it will be a 1% to 2% annual drag on returns.

Now contrast that profile with one of our larger positions, which is 20% of the portfolio and will contribute 30% of this year’s return. We’re happy with that, but don’t necessarily expect the company’s return contribution to grow significantly over time. To put it in the context of the considerations:

1.If this bet goes well, it should remain approximately 20% of the portfolio.

2.As a 20% position, this bet will immediately be a significant contributor to our returns if it goes well.

3.If this bet goes poorly, it will be an 8% to 10% annual drag on returns.

Given that profile, we wanted to take a big enough position now so that the investment would be a material contributor to the portfolio both now and in the future when other companies had grown at higher rates. But in order to take that upfront risk in light of consideration 3, we needed to be compensated for doing so, which we believe we were and are by the valuation we paid and also by being invested via a preferential share class that gives us favorable economics if the business significantly retrenches. So while there is concentration risk, it is mitigated in the near-term by the terms of our investment and in the long-term as our other investing decisions play out.

Having said that, I recognize that none of our investing decisions will play out according to plan. But that’s exactly why we should all try to build a thoughtful portfolio of some number of them sized accordingly.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Tremendous Upside Potential

Prompted on X nee Twitter to share an insult he’d never forget, our founder and CEO Brent told of the time (and he wasn’t making this up) a Deputy CIO at an Ivy League endowment told us they weren’t interested in investing with Permanent Equity because they were “only interested in opportunities with upside.” Having, at that time, recently moved my family to mid-Missouri to take a job at Permanent Equity precisely because I was interested in upside, the comment caught me a little flat-footed.

I think this Deputy CIO’s perspective was that because Permanent Equity invests in companies that do rudimentary things like build fences and then does uncreative things with the profits from those enterprises like distributing them to owners (hello, beer money), our returns were necessarily constrained. And while our approach was and is pretty exciting to me, I guess that is another way of looking at it.

But I was thinking about this whole idea of upside the other day as I watched the machinations in the stock of the newly public Trump Media & Technology Group (Nasdaq: DJT). What a curious situation that is…

In case you haven’t looked under the hood, this is a “business” that former (and perhaps future) President Donald J. Trump (clever ticker!) conceived of to compete with Twitter now X because they kept kicking him off the platform due to things he said that others thought he shouldn’t. But I put “business” in quotes because it’s not much of a business at all. Based on what was filed with the SEC (and let’s go out on a limb and say we can trust that), Trump Media & Technology Group lost $58M last year (though some of that was not beer money) on revenue of just $4M. Further, this “business” believes that “adhering to traditional key performance indicators, such as signups…might not align with the best interests of TMTG or its shareholders.”

Yikes!

Yet a recent market valuation of this “business” was more than $6B. To put that in context, Trump Media & Technology would be by many, many orders of magnitude the worst-performing business in the Permanent Equity portfolio, but by many, many, many, many, many orders of magnitude the most valuable. How does that work?

People are crazy is one answer, and it's not an unreasonable one. Trump Media & Technology is currently a terrible “business.” Not only is it incinerating cash, but its highly-respected audit firm issued a going concern notice (i.e., warning that the company could go bankrupt) at the same time it went public. But another answer is upside. Trump (the former maybe future President) has a lot of supporters and were they to all become loyal, paying sources of recurring revenue for Trump Media & Technology Group in some shape or fashion in the future, that terrible “business” could become a profitable one that delivers unconstrained returns.

But I dunno. $6B seems like an expensive call option on the counterfactual I just described (and people are catching onto this fact with the stock down some 50% since it was at that level).

At this point I’m reminded about the time (and this is dating me like most of my pop culture remembrances do) that ESPN blogger and now Spotify host Bill Simmons called out NBA commentator Hubie Brooks for assigning every unknown basketball prospect in the annual NBA draft with Tremendous Upside Potential. These were players who were not statistically elite, but had characteristics like height or the ability to shoot the lights out when guarded by a chair to maybe one day be. But very few ever panned out.

The point is that upside is not so different from imagination and that imagination is not so different from deception. And that’s the reason why we’re all conned so easily and/or pay up for the prospect of unconstrained returns, because believing something to be true that isn’t yet but could be is exhilarating.

In other words, Trump Media & Technology has Tremendous Upside Potential and probably more than Permanent Equity. But I’m good with Permanent Equity.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

What’s Enough Working Capital?

One negotiation that can get, shall I say, animated as we complete diligence on a deal and finish drafting the purchase agreement is the question of how much working capital needs to be left on a company’s balance sheet at close. The reason that’s so is because the answer to the question “What’s an appropriate amount of working capital for a particular business to have?” is a kind of tautology. The appropriate amount of working capital for a business to have is whatever amount of working capital it is appropriate for that business to have.

In other words, it depends and what it depends on is a wide variety of factors. These include, but are not limited to, what the business is trying to accomplish, whether or not it wants to grow and how much, what time of year it is, what the tenor of the working capital is (i.e., is some portion of the inventory slow-moving or receivables uncollectible), and what it is used to having. And don’t underestimate the importance of that last factor. If a business has historically operated with a lot of working capital and a cash cushion but hypothetically could not (again, most small business owners tend to be financially conservative), it won’t be able to flip a switch and operate well with an optimal level of working capital if it never has. People will behave differently with more financial pressure on them, and that pressure will manifest itself in the numbers.

Further, methodology matters. It’s easy for two parties to agree that they’ll calculate an average over an agreed upon lookback period, but the devil is in the details. If it’s an average, is it a mean or median? What if there is a large standard deviation? Would you handle it differently if it’s a seasonal business and it’s high season or not? Finally, what’s an appropriate lookback period and if it’s long, should you throw out outliers?

Finally, perspective matters (shoutout Miles’ Law). Assuming all parties are being intellectually honest, a buyer of a business wants enough to slightly-more-than-enough working capital to ensure that the business can operate in normal course post-close and won’t require an additional capital injection, whereas a seller wants no more than enough to ensure that they are transitioning a good asset, but also not leaving several hundred thousand dollars (or more) on the table.

Given these slightly-at-odds aims (which can be more than slightly-at-odds if people aren’t being intellectually honest) and all of the ambiguity around the question and calculation, that’s why these negotiations can get animated. So how do we handle that?

First, we show our work. We’ll never put out a number without also showing how it was derived and why. And if you disagree, we ask that you disagree not with our number, but show us where you disagree with our methodology.

Second, we typically won’t specify a number, but a range. We’re not here to nickel-and-dime anyone and hope our partners aren’t either. As long as we land somewhere that’s approximately fair, that’s good enough.

Third, we’re always happy to agree to an after-the-fact true-up to make sure that the amount of working capital a business had at close turned out to be appropriate. Because you only had enough working capital if you ended up having enough working capital.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Working on that White Paper

Back when I wrote about how to build a portfolio, I said that there may be a more in-depth white paper in my future. And while the plan is for that to still be the case, it turns out that trying to write an entire white paper at once is a pretty heavy lift. So in the spirit of turning one difficult-to-achieve big task into a larger number of easier-to-achieve smaller ones, I thought I might take our five tenets of portfolio construction one by one in this space and see what resonates.

As a reminder, if you’re trying to build a portfolio of any individual items that need to cohere to achieve a goal, here’s the checklist:

Know what you’re trying to accomplish.

Don’t risk more than you can afford to lose.

Diversify, but not too much.

Only take risks you’re compensated for taking.

Everything is more correlated than you think.

So if we’re going to take these one by one, let’s first figure out what we’re trying to accomplish. But before I get to hurdle rates and return thresholds, a short story about the u12 girls’ soccer team…

The team got moved up to a higher division this season and is therefore playing some tougher competition. One recent match against a reasonably tough opponent took place on a day when the wind was gusting up to 30 miles per hour. The girls won the coin toss and opted to play the first half with the wind, so the objective in a tie game with the wind at our back was to try to take a commanding lead. To wit, the coach fielded an attacking heavy portfolio of players and the team ended the half with a 3-0 lead.

But now with a commanding lead and facing a stiff headwind, the objective changed. That’s because all the team needed to do to win the match was not concede three goals. So the coach switched out several attacking players and replaced them with defenders in the back. They won the match 3-1.

Yet at the end of the match, some parents were frustrated. They wanted to know why their player had been subbed out when the first half had been so successful and cited as evidence the fact that the team lost the second half 1-0. And that’s one way to look at it. But the fact of the matter is that winning the second half wasn’t the objective. Rather, the objective was not to lose the second half 3-0 or worse, and while a more attacking-oriented line-up might have won the second-half outright, it would also have been much more likely to concede three goals. The defensive line-up, on the other hand, was unlikely to score any goals, but almost assuredly would not concede three or more.

In other words, in building a portfolio, objectives matter. And never try to accomplish more than you are trying to accomplish because in doing so you expose yourself to asymmetric risk. To use the soccer analogy, the incremental gain of winning the match 6-0 is not worth risking the catastrophic loss of turning a 3-0 lead into a 3-3 tie or a 3-4 defeat.

With regards to the definition of investing (“expend money with the expectation of achieving a profit”), knowing your objective means defining how much money you will invest and what the cost of that capital is in order to determine your investment’s capacity and required rate of return. Typically, those two things – capacity and rate of return – are inversely correlated. In other words, you are unlikely to find a strategy that can reasonably invest $1 trillion and double your money in a year, so it would be a bad idea to raise that much capital and bank on those returns.

If you’re investing your own money, your required rate of return should be equal to the return you could get taking little-to-no risk at all (i.e., US treasury rates) plus extra return commensurate with the risks you are taking. These risks can take many forms, but are academically calculated using proxies for traits such as volatility, creditworthiness, size, governance, liquidity, and more, which all try to layer in required return in recognition of the fact that a small, volatile, and poorly-managed private company is generally less likely to pay you back than a large, stable, well-run public one.

If you’re investing other people’s money (as we do at Permanent Equity), then those other people have likely calculated their own required rate of return and agreed to pay you only if you exceed it, so it’s pretty easy in this case to figure out what your minimum required rate of return is. In our case, we take no management fees of any kind and don’t get paid carry until our investors have earned a hurdle rate on their invested capital. We then receive a catch-up until we have earned our share and then split everything after that at a pre-agreed-upon percentage.

So one way of looking at that is that we shouldn’t get out of bed for any return less than what would pay us for our work, and that is indeed one way we look at it. Our objective writ large is to earn a return over time that more than reasonably compensates our investors and us.

Of course, achieving that is more nuanced than investing 100% in things that are expected to achieve that hurdle rate-plus because rarely do individual investments perform like they are projected to (some do better, others worse). So typically we try to underwrite things that will perform well in excess of that number in the expectation that we will be quite wrong every once in a while. Further, we demand higher returns from newer investments that are likely to correlate with existing investments because again there are diminishing returns from turning a 3-0 lead into a 6-0 win versus a 3-4 defeat.

If, on the other hand, you’re anything from an individual trying to retire to an endowment trying to fund a cause, establishing your objective means defining how much money you need to have at some point in the future and then working backwards to determine how much you have now and then calculating the sliding scale between the return you have to earn compared to the amount of money you need to regularly add to the portfolio in order to have that amount of money at that future time. If you are good at saving (if an individual) or raising (if an endowment) money, then your returns can be lower. If you’re not, they have to be higher.

Either way, if you have an objective and know what it takes to get there, it limits the scope of what’s possible and therefore increases the probability you can achieve it. And also, perhaps more importantly, prevents you from ever trying to accomplish more than you need to.

Have a great weekend.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Numbers Tell Stories

At the risk of sounding like too much of a nerd, my favorite financial statement is the balance sheet. That’s because while the income statement and statement of cash flows are useful in showing what may have happened at a business during any given period, the balance sheet is what tells you how a business is positioned for what might happen next (which can also reveal a lot of context about what previously happened). And that’s interesting.

What’s further interesting, and what tells you a lot about the state of the business, is when you can discern whether or not that positioning was proactive i.e., it was something the operator of the business deliberately did or reactive, i.e., it was something the operator of the business had to do because of outside circumstances. Here’s an example…

We saw some numbers from a construction business recently that purported to have made about $3M on $20M of revenue over the past year. Not bad!

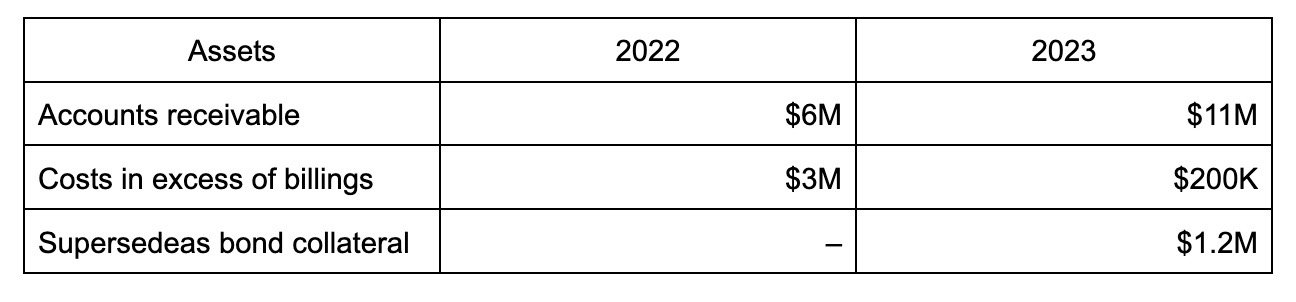

But the balance sheet told a different story. Here’s an excerpt from the asset side:

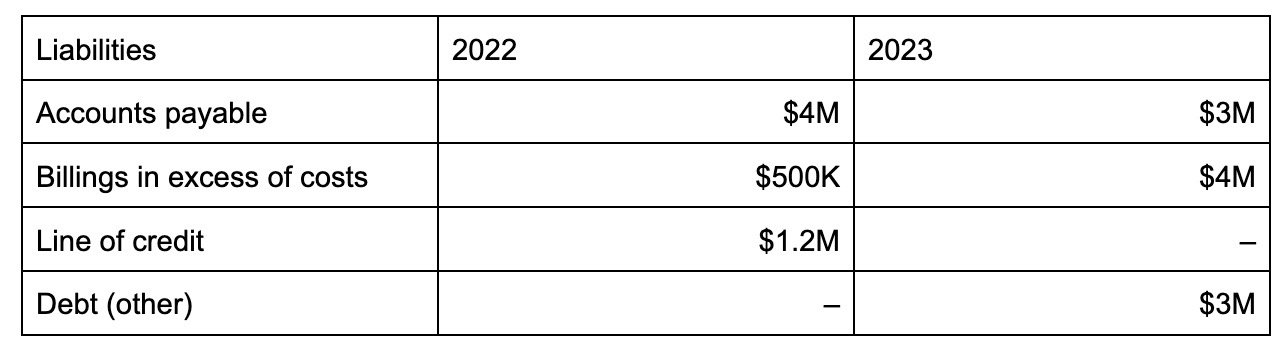

And the liabilities:

So despite “earning” $3M, here are some things that appear to be true based on how the construction business is currently positioned, as shown by its balance sheet:

Customers have stopped paying it in a timely manner (AR increase).

It’s gone from being underbilled to overbilled (i.e., it’s trying to get paid for work it hasn’t done yet).

It had to post more than $1M of collateral to its bonding company (presumably because there’s a job out there the bonding company doesn’t think the construction business has the ability to finish).

Its suppliers are demanding to be paid faster (AP decrease)

Its bank called in its line of credit (balance went to zero).

It replaced that low-cost, vanilla debt with millions of dollars of debt in the more ominous category of “other” (which probably carries a higher rate and is covenant heavy).

This, in other words, is a business that has lost agency and has been put in a position by its outside stakeholders to be on the verge of running out of money. If I had to guess what happened, the business had at least one or two major jobs turn bad, but hasn’t recognized those losses on its WIP report (shoutout Procore, it’s good software) yet. In other words, it’s either trying to hide them or is in denial. But, and this is important, the rumor mill most assuredly knows what’s up so people who owe the business money aren’t paying (because they know they may never have to) and the people the business owes money to are demanding to be paid now (in order to get as much out of it as possible before it goes under).

Not great!

Ultimately, business and investing are forward-looking enterprises and the only financial statement that can give you a clue about what’s to come is the balance sheet. Which is why it’s my favorite.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

How to Add Value Post-Close

One thing that I’ve found to be true of most small business owners is that they are fairly financially conservative. That’s because despite being wealthy, most of their net worth is tied up in an asset (the business) that has a lot of people relying on it and is always seemingly a few bad months in a row away from a crisis. So they try to keep costs down and cash in their pockets.

That was the context I gave when I was on a call recently with two gentlemen who wanted to get into the business of acquiring companies and asked me what areas, when we were both underwriting potential investments and helping operate post-close, we could reliably add the most value. And while I said that we typically don’t underwrite to being able to be helpful at all (shoutout margin of safety), we’ve historically been helpful in four areas: hiring (shoutout Kelie), marketing (shoutout Emily), technology (shoutout Johnny), and financials (shoutout Nikki and team).

What’s interesting about these four areas is that they are four areas that a reasonable, but financially conservative, small business owner might view as cost centers. In other words, why pay people to recruit for you when you can do it for free through word of mouth? Or why buy online advertising if you can’t tell how many conversions it drives? Or why get a pricey ERP when a spiral notebook works just fine? And finally why do anything more than file the required tax returns?

Again, each one of these stances makes sense on its face in this context, but without top-notch people, effective marketing, reliable and useful technology, and timely and accurate financials, a business can’t grow. So when Permanent Equity steps in and encourages investment in these areas, while we do hear some grumbling about the cost, we typically get a pretty good return because (1) these areas are important and (2) they have historically not been invested in.

Back when I wrote about brewing the world’s best cup of coffee I mentioned the three paradigms that describe what might lead to success. One is you’re only as strong as your weakest link, i.e. the best you can do is your worst input so always try to raise up your laggards.

In the case of trying to add value to small business operations after making an investment, I think this is the paradigm that best applies. In other words, be useful in an area that’s important but that the previous operator viewed as useless. That’s because nothing (or not much) is likely to have been done in the area before and doing something that’s important is usually reliably better than not doing that something important at all.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Day 2

At Amazon it’s supposed to always be Day 1. What this means is that anything is possible if you stay “constantly curious, nimble, and experimental.”

As for day 2, well, that’s what you want to avoid. Because as founder and then CEO Jeff Bezos joked at an all-hands meeting, day 2 “is stasis followed by irrelevance followed by excruciating painful decline followed by death.” And as someone who sits here 40-plus years old with acute tennis elbow after getting smoked in a casual game of pickleball, that hits a little too close to home. But does day 2 get a bad rap?

I thought about this recently when my daughter got a new phone. See, before she traded in her old phone, she made sure to transfer all of the photos on it that she wanted to keep. I was looking at those pictures with her as she did this and among them were her as a 3- and 4- and 5-year-old playing soccer with me coaching in the background. I about cried (which is becoming a recurring theme here) reliving those moments.

One takeaway from that is that sentimentality increases exponentially with age. Another, since she wanted to save them, is that teenagers may actually care about stuff (though the jury is still out on that)...

But she was offended when I remarked that I missed those days. Because why would I miss those days when I have these days? And that was an interesting question because I love these days. What’s different from then to now, though, is (1) we have fewer days left and so therefore (2) there is less open-ended-ness.

In other words, and to be brutally honest, even though I try to be curious, nimble, and experimental, it’s not day 1 for me anymore (and also not for Amazon either). I’ve done things and made decisions that specifically preclude me from doing other things and making other decisions which means that not anything is possible for me. That said, it oversimplifies it (I hope) to say that if I’m on to day 2 (or 3 or 4) with a diminished opportunity set that I’m headed for irrelevance and excruciating painful decline.

That’s because here on day 2 (or 3 or 4) I’m building on previous choices made to take a step (or steps) forward. So while my scope of opportunity is narrowing, the magnitude of significance of what’s left to do is growing.

When I previously about cried prior to spring break, I wrote that you or the world is always moving on, and I stand by that. But the thing about that statement is that it’s simultaneously something to be lamented and celebrated. To wit, I miss my little kids, but I love my kids.

So the thing to avoid isn’t day 2 because day 2 (or 3 or 4) is inevitable. The thing to avoid, as Bezos rightly notes, is stasis.

So wherever you are, personally or professionally, recognize that you won’t be there for long and further that you can’t (and hopefully don’t want to) go back to where you once were. You’re headed somewhere next and that also means not being headed to an increasing number of other places. For that to be something to celebrate and not lament, be intentional with your investments of – and in – time, capital, opportunities, and people. You can’t do it all, but do what you can.

Here’s to Day 2.

-Tim