Why Plans Don’t Work Out

In Florida in 1987, professional wrestlers Bruiser Brody and Lex Luger tied up at the beginning of what was supposed to be a standard cage match. And that’s the last time anything went according to plan. After several strange minutes, it turned into a total shoot – any unplanned, unscripted, or real-life occurrence in a wrestling event. Brody simply stopped reacting to anything Luger did to him. Not in a “I’m invincible and even your best can’t rattle me” way, but in a “your punches aren’t real and I don’t have to react to them” way. Eventually the referee called for a disqualification, and Luger escaped over the top of the cage.

Professional wrestling is arguably one of the most planned events in sports – stop somebody on the street and they’ll probably call it “fake.” We all know it’s scripted, choreographed, practiced, fine-tuned – in other words, planned to within an inch of its life. But even the seemingly best-laid plans can go wrong, whether in wrestling or business operations. And yet we still plan, and plan obsessively.

Uncertainty > The Plan

People crave certainty, particularly as the world around them feels increasingly uncertain. We see this in every piece of our own business, as well as the businesses we talk to. Certainty is a comforting narrative. And, if you’re a business owner or operator, you’ve got to plan. This is, after all, the Season for Strategic Planning™.

What most people don’t acknowledge when in the depths of strategic planning, however, is that plans can actually disguise uncertainty rather than reduce it. (See the Lin Wells memo for a powerful illustration of the dangers of acting on our predictions with too much conviction in an unpredictable world. One example? In 1930, the defense planning standard was “no wars for 10 years”; WWII began a mere 9 years later.) Plans made rigidly and without acknowledging the unknown unknowns run a very real risk of imploding when they run up against incomplete knowledge about the world, misunderstandings about the connections between our present actions and their eventual outcomes, and the competing and unexpected contingencies that affect both.

There are many, many reasons plans don’t work out, go awry, fall apart, or fail, but they’re all related to Goodhart’s Law. The formal version of Goodhart’s Law is this: “Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.” Often invoked in relation to measurements and metrics, another flavor is “Nothing remains stationary if we can influence it.” And, we can influence a surprising number of things in an incomprehensible number of ways.

If things were to go exactly as planned, it would mean:

We completely understand the situation and information

Nothing changes

No one influences it

If you’re keeping score, that ultimately means that no plan will 100% work 100% of the time – once in a lifetime fires occur, pandemics hit, market environments shift, search algorithms alter, wrestlers go rogue… At the end of the day, problems are rarely completely specified and humans are humans with their own wants, needs, expectations, agendas, emotions, and egos.

Here’s a short and incomplete (hello unknown unknowns) list of why plans don’t work out:

Incomplete information: Complete information is a fool’s errand. Rarely are operating decisions based on static facts or knowledge. The real danger is in planning without flexibility or contingencies, blindly trusting probabilistic reasoning without admitting that underlying circumstances are changing all the time, and not acknowledging the uncertainty underlying your plans. (A once-in-a-century fire encroaches on a storage area thought safe.)

Pride: Plans go wrong when our pride overshadows our judgment. Plans based on wishful thinking, outsized estimations of our ability, influence, or knowledge, or a belief that we’re the only one that can make the plan are inherently brittle. (A leader’s clutching to plans because they’re their plans.)

Unreasonable expectations: The saying goes, “if you say you can’t, you can’t.” But the inverse isn’t always helpful. High optimism is actually one of the ways to plan in light of uncertainty – even though we craft plans based on past experience, we may not be capable of envisioning the full range of possible futures. This is different, though, from assuming that things will always go according to plan and implementing things like timelines and budgets based on delusional optimism. (A new hire is made to tackle three big projects – time constraints mean they’re only able to tackle one, at most.)

Flawed assumptions: When trying to solve for uncertainty, we tend to rely on gut instincts that overemphasize recent events (recency bias), downplay information that doesn’t conform to what we think we know (framing effect), pressure us to act sooner than we need to (action-oriented bias), attach ourselves to an initial idea (anchoring bias), or ignore data that doesn’t fit what we want the plan to be (confirmation bias). Left unchecked, our personal and organizational biases undermine the planning process – and the plan. (Assuming inventory is moving, but the data tells a different story.)

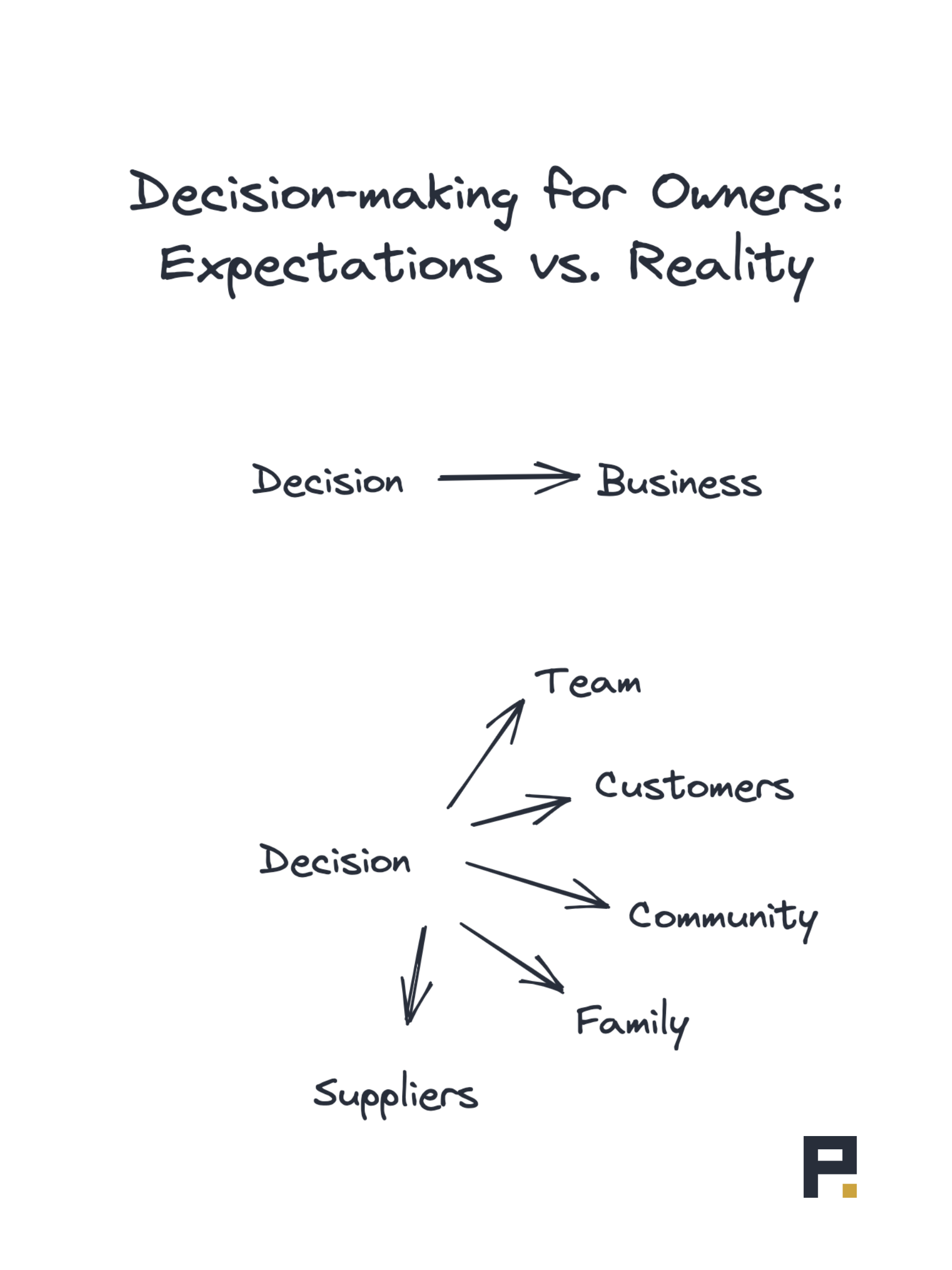

Forgetting that other people exist: You don’t exist in a vacuum – in your life or in your company – and neither do plans. Good planning requires communication, buy-in, relationship-building, and feedback from the people actually implementing and executing those plans. Failing to consider the concentric waves of people affected by or affecting your plans as you’re making and acting on them opens up many avenues for them to fall apart. (Anticipating backfilling a critical position with someone who’s job-hunting elsewhere.)

False positives: Did the plan succeed because of a good plan or because of good luck? One of the most dangerous effects of planning for the future based on past experience. (Expanding to a new market and assuming the same plan will translate.)

Ignoring the plan (or blindly following it): We do not recommend making a plan and never looking at it again. Follow it as far as makes rational sense and update it as much and as robustly as necessary. (Running the same playbook when growth is faster than expected.)

The wrong motivation: Here, the plans you’re making are not to provide genuine guidelines, benchmarks, next steps, or collective postures. Instead, the underlying reasons for planning might be masking insecurity or incompetence, promoting productivity as an end goal, showing off what you know, trying to impress, or prioritizing the wrong metrics. (An impressively creative communications plan, rather than one optimized for what will convert customers.)

If we’re being honest, almost every plan goes sideways for those first two reasons: Unknown unknowns and pride (frequently about what you do or don’t know). Not to confuse our sports, but we’re with Mike Tyson on this one: “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” It’s how you’re equipped – or not – to deal with the aftermath that counts.

Planning > The Plan

Good plans are often wrong. They are subject to unanticipated outside forces. They come up against unpredictable obstacles. They collapse on an individual’s motives, global events, or an isolated breakdown. The point is this: We can’t judge plans based (solely) on their outcomes. Sometimes that unexpected outcome in the aftermath of a plan’s failure can be more useful or teach a valuable lesson or open up new and unanticipated opportunities.

When people are making plans with the underlying goal of forcing certainty onto an uncertain world, they welcome false conviction. These false narratives are a detriment to setting the table well, and they also close doors to other possibilities.

As John Kay and Mervyn King write in Radical Uncertainty, “Knowledge of the underlying processes is imperfect, the processes themselves are constantly changing, and the ways in which they operate depend not just on what people do, but on what people think.” Or, more simply, “Real households, real businesses, and real governments do not optimize, they cope.”

So if the world is uncertain, Goodhart’s law applies, and there are always unknown variables, why plan anyway? As an operator, you need plans for budgets, brand pivots, hiring pushes, product development, fulfillment, supply chain management, pricing, and communications. You plan because you need a coherent why, because you need actionable steps, because you’ve identified bottlenecks and actions that you hope will move the needle.

Plans are also critical because, even if they fall apart in the worst way, they give you valuable feedback loops and benchmarks against which to gauge performance. Fundamentally, as a small business operator (and as a human in the world), you’ve got to make decisions, even if the stories we tell ourselves about decision-making, risk, and probabilistic thinking are flawed and incomplete.

So how do you do it? One strategy is to try to plan more and plan better, whether it’s more data, more granularity, more action items, or more control. Ultimately, to try to make things fixed, stationary, knowable, and plannable. Even typing this feels fragile.

The problem with trying to impose order onto the uncertain is that you’re always going to get punched in the mouth.

The Posture > The Plan

The very best wrestling is never really, fully scripted. But it’s not all a shoot, either. Peak wrestling matches are about holding plans loosely while maintaining maximum flexibility. Yes, matches will occasionally veer into the entirely unexpected, but good wrestlers are conditioned to respond to the unanticipated, continuously update the plan based on what’s working with the audience, their chemistry with each other, and whether or not anyone’s injured, and remain flexible and agile in the face of plans that go sideways.

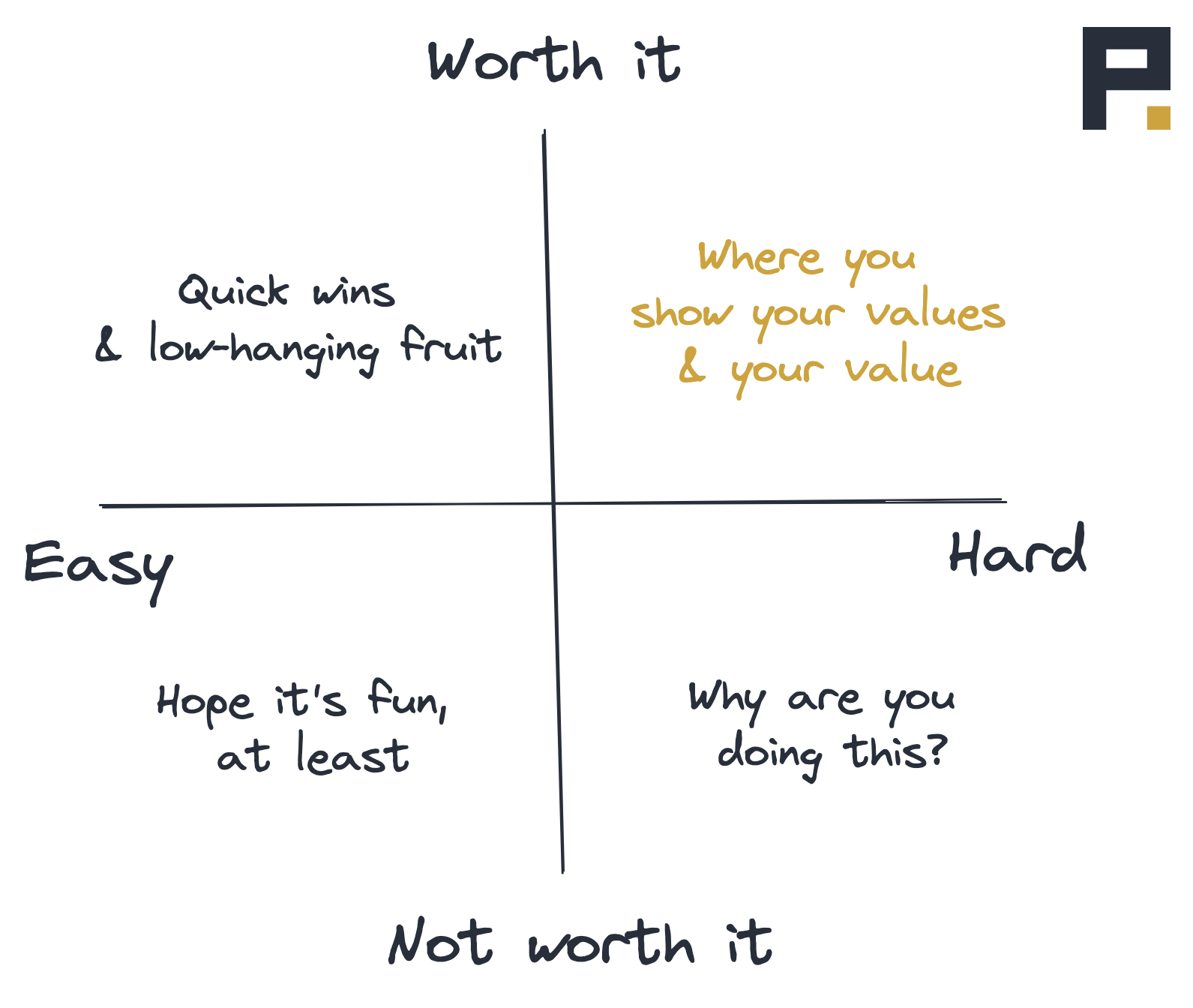

For us, planning with uncertainty is figuring out how to build the only sure thing – that things won’t go according to plan – into the plan. We think the best way to do this is to approach each situation with high intellectual honesty, high humility, high optimism, and a growth mindset. It’s a posture, over a plan, that embraces learning, adaptation, and iteration while understanding that plans don’t have finish lines.

In an uncertain world, this posture towards strategic planning requires humility – an acknowledgement that we do not have perfect information nor do we know what the future will hold. It requires identifying reference models and narratives to act as guides while understanding that there are many alternative future scenarios. It requires preparation and conditioning to make sure, as much as possible, that you and your business are primed to respond when things go awry. It requires long time horizons to allow for Bayesian updating, adjustments, and recovery. It requires acquiring and retaining as many options as possible while understanding that plans and decisions necessarily reduce future options. It requires harnessing the power of choice and focus while remaining flexible.

And, sometimes that posture falters too. But if the posture is one that holds plans loosely, accepts that you might be wrong, updates for new information, and makes room for others and their plans, you can always plan for what’s next.

You’ve still got to plan. For ops plays & wisdom, subscribe to Permanent Playbook.