Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions delivered to your inbox.

Zero Tolerance OR Materiality

Clayton (who runs Capital Camp) emailed me after I wrote about the fine line between having a zero tolerance policy towards errors versus focusing on material issues only. What, he asked, is a tolerable amount of slippage in a situation and what variables should go into making that case by case decision?

It’s a good question because there’s no good answer, but here are some considerations…

If you see a small problem, whether you address it or not probably depends on how fast it is likely to get worse and what the ultimate downside is when it does. In my previous example of small, questionable credit card charges turning into full-scale fraud if they’re not caught early, the rate of decay of the problem is exponential and the downside tremendous. Because when the thieves see that they can get away with something small, their next gambit is likely to max out the card, so zero tolerance applies.

But if a small problem is ring-fenced i.e., even if it does get bigger, it can't escape or become material, let it fester. This applies a lot in parenting where by letting a small problem persist, your kiddo usually learns how to solve it on their own terms. And does it really matter if yours is the one never wearing shoes?

A third way is to let a problem linger, but watch it like a hawk so you can intervene if it runs the risk of becoming material and spilling over. This is more time-consuming than either a zero tolerance or materiality approach, but you get some of the benefits of both. Of course, this approach can be dangerous in that it’s also egotistical. If you adopt it, it means that you think you will know the right time to step-in and be able to put something back on the rails which, you know, is the entire premise of Jurassic Park.

And a fourth is that you allow a problem to continue because you are deriving a benefit from it somewhere else and therefore are tolerating a material issue because the entire equation of variables nets to immateriality. A classic example of this is the employee that contributes greatly to the P&L and is a drag on culture…like a copywriter I once worked with who authored high ROI campaigns but also diminished the brand and berated coworkers. This one is difficult to manage because by solving the problem you are creating another problem. I think the tactic here is to celebrate the good but set benchmarks around the bad and cut bait if the negative side of the equation doesn’t show signs of improving.

But you need to decide for yourself what is and isn’t worth it.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Howard Schultz: 3x Starbucks CEO

Hulk Hogan is the best WWE champion ever. I agree. But then you have this nonsense where wrestlers like Brock Lesnar are aggrandized for being a 12-time world champion.

Being a 12-time world champion is great and all, but it also means you lost the championship and had to win it back 11 times.

Of course, professional wrestling outcomes are preordained, so who cares? But why is Howard Schultz the three-time CEO of Starbucks?

I met the second Howard Schultz replacement way back when, when the two of them came to speak at an event I attended and you could tell immediately he wouldn’t last long. His name was Jim Donald and he was from Pathmark (a low quality now mostly defunct chain of grocery stores in the Northeast) and the two just didn’t coalesce. This was 2005-ish and Schutlz re-replaced him by 2008. You could tell seeing them interact it wasn’t a long-term fit and when Schultz talked over Donald on investor conference calls it was awkward.

Schultz stayed in his second stint as CEO until 2017 but then stepped back in again in 2022 after the person who replaced him retired.

Now it’s 2023 and Schultz permanently retired last week with his fourth replacement having learned under his tutelage since September. We’ll see how it goes, but I suspect Starbucks hasn’t seen the last of Howard Schultz.

And maybe that’s a good thing. Here’s a long-term chart of Starbucks stock. I’ve highlighted the times when Howard Schultz was CEO.

The stock has mostly performed a lot better with him in charge. But this seems like a failure in transition planning, no?

A successful organization cannot be led by one and only one individual. Nor should an individual believe that he or she is the only one who can lead a specific organization. Because if that’s the case, it’s only a matter of time before the wheels come off.

If you’re a leader, the most valuable way you can spend your time is on training your replacement. Maybe Schultz knows this now and that’s why he’s spent the last seven months training newly minted Starbucks CEO Laxman Narasimhan. We shall see.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Why We Negotiate for Worthless Terms

There I was, sitting at my desk, my HP laptop overheating as I tried to build a model in Excel that simulated 5,000 random 25-year sequences of events helping Caroline demonstrate to an outside independent auditor that a preferential term we had built into our equity at one of our investments wasn’t worth anything.

First, a note about auditors, regulators, or really anyone tasked with oversight. When they show up to examine you, they will find something wrong. That’s their job and people like to show the people they report to that they can do their job (mostly). So if you have that mindset going into one of these situations, you can leave a lot of frustration on the cutting room floor.

Back to my overheating laptop…

What I think the auditors were skeptical of is the fact that we had negotiated for a term that on its face wasn’t worth very much. In this case we’d been asked to pay a higher valuation than we normally would to make an investment. We wanted to do it – we liked the business, people, and opportunity – but we also didn’t want to get our asses handed to us because we overpaid. Remember, the only way to definitively lose a game is if it doesn’t end on your terms.

So we said to our prospective partners something like: Look, if reality is within spitting distance of plan, we’ll split everything pro rata, but if the bottom falls out, we get all of the earnings until the business recovers. And the only reason for that is that we’re investing at a valuation where we can’t hazard the risk of the bottom falling out and only get part of the economics.

Because we both believed there was a low probability of that happening, they said fine.

My Excel spreadsheet proved that assumption out. The median value of all of those randomizations was zero and the mean was immaterial. So there was a chance the preference could come into play, but it was indeed a small one.

So why did we negotiate for a “worthless” term? Because we never want the game to end.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

On Alien Abduction Insurance

Back when I wondered why insurance is legal, I talked about unusual insurance and noted that there was absolutely something to be written about alien abduction insurance. Well, reader Matthew Queen, who designs captive insurance solutions for a living, saved me the work.

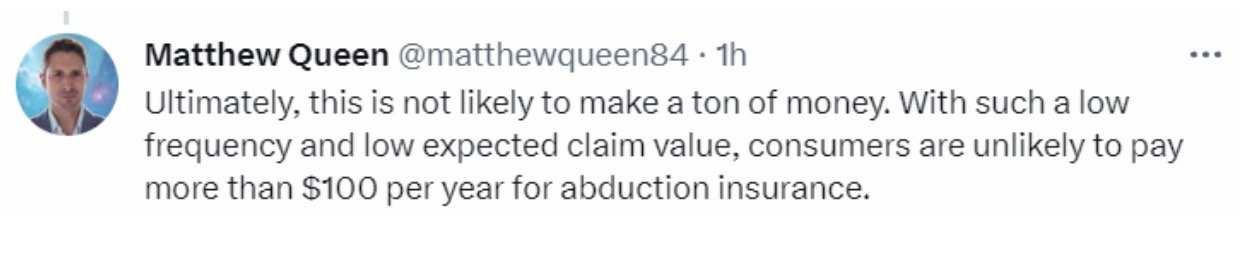

After noting the frequency of the risk…

And the magnitude…

He concludes that it’s not likely to be a profitable line of business for an insurer…

So, so much for that alien abduction insurance start-up you were planning. Enjoy the weekend.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Why Banks Prefer Low Returns

People who know me know that the concept of cost of capital is near and dear to my heart, so I read with great interest this new practical guide to measuring it from the financial mind of Michael Mauboussin. The whole thing is worth reading, but the first eight pages are particularly good at clarifying what can be a very abstract concept.

All things being equal, a company should prefer a lower cost of capital to a higher one because it lowers the threshold return a company needs to generate in order to create value. The catch-22 of that is that the cost of capital from an investor goes down alongside the investor’s perceived riskiness of the investment. In other words, if you’re able to somehow guarantee an investor a return, they won’t ask for much of one. This is why bank debt backed by assets is relatively cheap (i.e. has a lower interest rate) compared to what a VC will ask for to provide funding to a money-losing start-up.

The reason I think that’s a catch-22 is because the more you guarantee an investor in order to lower your cost of capital (in loans these guarantees are called covenants), the less flexibility you have to run your business, which increases all kinds of hard-to-quantify costs. If you have to pay the bank, for example, you may not be able to hire a team to pursue a greenfield project.

Moreover, as Mauboussin points out, having investors with senior claims on cash flow increases the odds of financial distress even if the objective cost of capital is low. Put another way, if you take on too much low cost capital (i.e. debt), you will end up increasing your cost of capital because the more guarantees you make the less likely you are to satisfy them all.

So what’s an optimal capital structure? That depends on what you’re optimizing for.

If you’re optimizing for near-term returns, the answer is as much low cost capital (i.e. debt) that a business can tolerate without tipping it into distress (which is why traditional private equity closes levered transactions). But if you’re optimizing for the very long term, I think the answer is very little to no debt at all (which is what we do). The reason is then you have maximum flexibility and the opportunity to allocate capital that while more expensive, has the chance to go into ideas and opportunities where the spread between what the capital costs and what it might return is highest.

We call this creating variance and while it makes some investors (like banks) nervous, that’s why they get really cheap capital (customer deposits) and prefer to earn lower returns.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Silicon Valley Lemmings

We love The Oregon Trail in our office and often compare the travails of our businesses to challenges in that classic video game, but gun to my head, Lemmings is a better game.

If you don’t know Lemmings, it’s a classic puzzle game where you have to devise a strategy to save a column of unceasing marchers from certain doom by changing something about the make-up of the level. If you don’t, they all march off a cliff together and game over.

I hadn’t played Lemmings in a while but it came top of mind after I read this quote from a now former executive at Silicon Valley Bank: “It turned out that one of the biggest risks to our business model was catering to a very tightly knit group of investors who exhibit herd-like mentalities.” So that’s who my kids have to thank for their new screen time jam.

If you don’t know Silicon Valley Bank, it’s the bank that collapsed not long ago in the second-largest bank failure in history when venture capitalists and their portfolio companies started withdrawing deposits en masse alarmed by mark-to-market losses on the asset side of the bank’s balance sheet. Not many people with bank accounts internalize the fact that we (yes, anyone with a bank account) are lenders to banks, but we are and when we take money out of our accounts, we are effectively calling in debt the bank owes to us.

I don’t know if you have debt yourself, but if you do, it would probably be hugely unnerving if the thing you owed money to might ask you to repay it at any time. Rather, you’d want to know when you have to pay them so you could plan. When it comes to checking accounts, banks don’t do this, which to paraphrase Sun Tzu is both their greatest strength and greatest weakness. Which brings us back to Lemmings…

What in the world was Silicon Valley Bank doing focusing on one very specific type of customer all of whom would panic on social media and react the same way when the asset side of the bank’s balance sheet started looking shaky? (David, Nikki, and I talked a little bit about this and what small businesses can do to protect themselves against bank runs on a recent podcast.)

The thing about video game lemmings is that they all behave the same. And even if you change something about their environment, they all respond to that change the same. This creates an inherently fragile environment (which is why it’s a fun game!) But fragile environments where everyone can unpredictably act the same all at the same time are not fun in business or in life (as Silicon Valley Bank discovered when their depositors became real world lemmings).

What’s weird is that it’s often easiest to do the same thing over and over, especially when it’s working. The catch-22 is that when that one thing stops working, there is no thing to fall back on.

So when things are working, make life more difficult for yourself by going out of your way to cultivate difference. It won’t be as easy or as fun or as profitable, but it could come in handy down the line. For Silicon Valley Bank perhaps that could have taken the form of making and taking more loans and deposits to and from real world businesses in small-town America that were cash flow positive. Alas, we’ll never know.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Zero Tolerance for Materiality

Back when I was America’s favorite least qualified CFO I spent a lot of time thinking about materiality thresholds. This is the accounting concept that you can’t audit everything, so if you end up within 5% of reality, it’s fine.

On the one hand, that idea is a huge time saver. If something is not going to move the numbers by a meaningful amount, why do the work of nailing it down? But on the other, it’s hugely unsettling. How can you put something out to the world knowing full well that it’s wrong? Moreover, doesn’t materiality depend on quality and not just quantity?

I watch our credit card statement like a hawk. I’m paranoid about fraudulent charges and the mess that such things create. This paranoia was compounded when I learned that fraudsters and thieves are most likely to make small charges to your credit card before making big ones to see if you notice. And if you let those slide because the hassle of calling your credit card company outweighs the expense amount, you’re likely signing up for a big problem.

So that’s an example of a case where a zero tolerance policy makes sense.

There’s tension between these two ideas, materiality versus zero tolerance. When does one apply and not the other?

We encounter this tension often when diligencing investments because companies are rarely exactly as they are presented in CIMs. What amount of slippage is tolerable versus what prompts renegotiation versus what would cause us to walk away? The line is fine and it always depends.

But what we do know is that problems never get better on their own. So if you let something slide because it’s immaterial, know that it’s likely to become material eventually.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Does This Matter?

Back in January David (our creative director) shared an early cut of the podcast Brent, Mark, and I recorded to go along with Brent’s annual letter and asked me what I thought. I listened to it and responded “Let me think about it.”

The thing was, there was a lot of banter and not much of it was about business or investing. It also felt casual. Did we need to be more serious?

David took the feedback, made some edits, and we ultimately published a version of it. So it was with some trepidation that I shortly thereafter received an email from one of our larger investors that read “I just listened to the podcast. We need to talk.”

When we got on the phone he said that he was so thankful that we recorded that podcast. It helped clear up for him stress he felt around what he believed to be the biggest risk to his Permanent Equity investment. “My concern with your 27-year structure was that the team wouldn’t stick together for the duration of the fund life,” he said, “but I think you guys actually like each other.”

We put a lot of time, effort, thought, and rigor into the materials we provide to investors. It kind of sent my head spinning that this one’s most significant concern about us was mitigated by listening to us shoot the shit for an hour. But it also made perfect sense.

This got me thinking about what we think matters or doesn’t matter and what actually matters. If we think something matters and it actually does, great. And if we think something doesn’t and it doesn’t, perfect. But if we think something does and it doesn’t or it doesn’t and it does, that’s bad.

I think it matters a lot that you like the people you work with. You spend a lot of time with them and everything is easier when you have a genuine relationship. But I’ll be honest that until recently I hadn’t spent much energy thinking about how we might best demonstrate to others that the people on the Permanent Equity team like each other…or that we even needed to.

But that’s why it’s important to try to know what matters and what doesn’t.

We see this all of the time in deals. What matters to a seller often is a higher valuation and what doesn’t is standing behind her projections because she’s confident she will hit them. What matters to us is getting the performance we’re paying for. Ergo we can value the deal to the projections but structure it so we buy less than 100% of the company but get 100% of the return if they’re not achieved.

You also see it in compensation. An employee can be compensated in lots of currencies: guaranteed dollars, performance bonuses, equity, vacation days, etc. Some of these the employee will value more than others and some the employer will value more than others. The key here is to not transact in a denomination with a wide bid/ask spread, because then neither will be satisfied.

Of course, it’s self-evident that if one thinks x and another thinks y, the two won’t be aligned. But it’s remarkable how often it’s so hard to know what another is thinking.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Even More CIMple Truths

As always, we have empathy for the analysts at investment banks tasked with putting together lengthy decks about small private businesses (aka Confidential Information Memorandums or CIMs for those not in the know). Information is often incomplete or missing altogether, there are skeletons in the closet, and the people approving your work probably don’t appreciate how difficult it is to make a color pop.

That said, we occasionally see some things that make us scratch our heads. In no particular order…

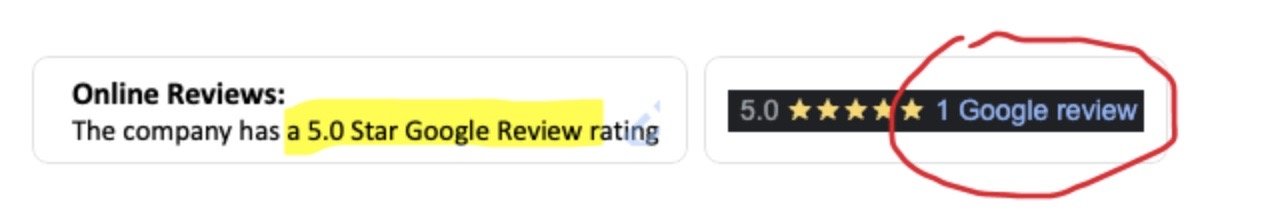

Statistical insignificance

Fact check: true?

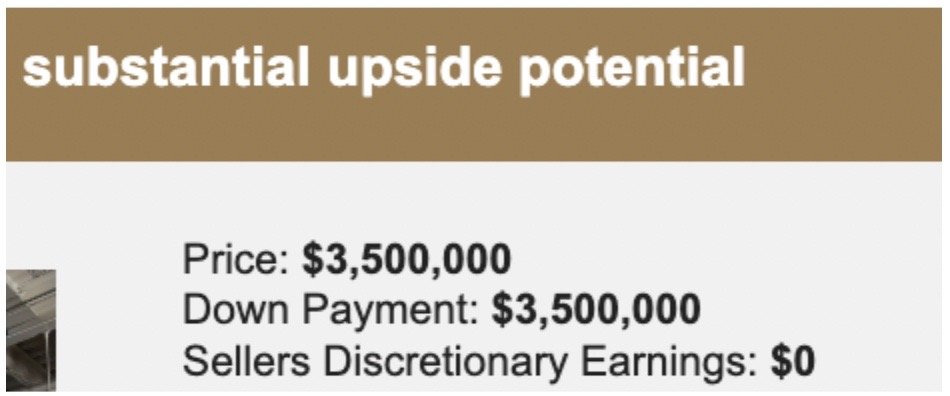

Eternal optimism

Because from zero, there is nowhere to go but up. Cue Shania Twain.

Whatever this is

Cash flow more than two times sales? Not sure how you do that, but good work if you can get it.

Have a great weekend.

– Witnessed by Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Kansas Basketball and the Value of Money

I played basketball some growing up and remain a big college basketball fan so when Lori (our Director of Operations) asked me during my onboarding process what some things I might do were now that I had moved to the midwest, it seemed logical to me that a stop at historic Allen Fieldhouse (the home of Kansas basketball) should be on the list. New to Missouri, I didn’t yet appreciate how deep the rivalry ran, so I was surprised when Lori responded, “Really? Why would anyone ever want to go there?”

Fast forward and thanks to Mark’s Kansas connections, I was finally able to make it happen this year and it was as advertised. The atmosphere was great and the history compelling.

The next day Emily’s husband Chris, a Mizzou alum and diehard, called me and said, “So, how was Allen?”

“It was pretty great,” I said.

“I was afraid you were going to say that,” he grumbled.

And that right there is the difference between objective and subjective value.

Objective value is what an item is actually worth. A dollar is worth a dollar, for example, because you can pay a dollar’s worth of taxes with it. Subjective value, on the other hand, is what you perceive an item to be worth, which is an amount informed by all of your life’s experiences. If, for example, you had no taste buds, then the going price of caviar would make no sense!

Lori’s and Chris’ subjective valuations of a visit to Allen Fieldhouse were low because, you know, Missouri (even if Chris was aware of his bias). Mine was higher because, you know, basketball. Others will be higher or lower than any of ours depending on their circumstances but probably not exactly equal to anyone else’s.

And that’s fine. That’s why we have money.

Money is important because it’s the thing that allows us all to convert subjective valuations into objective ones and therefore transact more efficiently. If I told you I’d trade my house for yours, you’d have a lot to figure out before you said yes or no. But if I made you an offer in dollar terms, you’d probably be able to say yes or no within the hour.

And yet even the value of money can be made subjective with the introduction of other variables around it such as time. In fact, I’d argue that knowing when you will get paid is in some cases far more important than knowing how much you will get paid.

The point is if you’re doing a transaction and it makes sense for you to do it, do it. Or if it doesn’t, don’t. Just don’t spend time worrying about the deal your counterparty thinks he or she is getting or what the world might think. Because no one will evaluate the outcome the same way you will.

And not only is that ok, it’s kind of the point.

P.S. Enjoy March Madness whether you’re Rock, Chalk, M-I-Z!, or something in between.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

On Bankability

Since I’m interested in probabilities and predictions, one of my favorite online feuds is that between Superforecasting author Philip Tetlock and Black Swan author Nassim Nicholas Taleb. So I was intrigued the other day when Taleb tweeted that his reply to Superforecasting is forthcoming. In it he asks the very fair question “If they claim to be so good at forecasting, and their forecasts are actionable and related to reality, why aren’t they so rich?”

Look, everything isn’t about money, but money is a very interesting way of keeping score. This is why Taleb, in the conclusion, recommends that superforecasting be applied to “bankable” events. That means those where knowing the future can be translated into “dollars and cents.”

This got me thinking about bankability and how it applies to everyday life. If I spend time going for a run, is that bankable? Is doing a crossword puzzle bankable? Should everything be bankable or is it okay for some things not to be? Is there such a thing as non-cash bankability?

Mark (our COO) has a paradigm (that follows) for when it comes to helping our operating companies create new capabilities inside of their businesses. He asks, “Do we need to know how to build the capability or do we just need the benefit of the capability?” If the former, we should probably hire for it, develop it, and sustain it. If the latter, we should probably buy it or outsource it.

In other words, which part of what needs to happen for us to move forward is most bankable? Because that’s where we should put our chips.

I don’t think everything is about money, but I do think actions should have expected, measurable, and concrete outcomes in order to be worthwhile. Maybe that’s crass, or transactional, but before I do anything now I do find myself asking “Is it bankable? How? If not, why?”

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

What’s the Cost of Entropy

Emily, David and I recorded a podcast recently where we discussed current market conditions and what sellers might expect from buyers in 2023. During that discussion I said at least one thing that David thought was incredibly self-interested and another that Emily thought maybe I shouldn’t have.

I stand behind both statements, and I’ll explain why.

What David thought was self-interested was when I advised sellers, when it comes to deciding what offer to take, to not let the most money tail wag the good decision dog. It’s self-interested because as a buyer of businesses that is measured on returns, we ostensibly benefit by paying less. Moreover, our offers tend to value differentiators that are not money (which is a commodity), so if we can get sellers to value those differentiators like we do, we win.

That’s one way of looking at it, but it ignores the fact that those differentiators do have value and that costs can be measured in units other than dollars. Time is a cost. Anguish is a cost. Uncertainty is a cost. Volatility is a cost. So if you can get more money but it means you have to stay involved with the business longer, lay off tenured employees, agree to accept an earnout or other contingent payment, and work to pay down debt, maybe that offer isn’t worth as much as the headline value. To make a true apples to apples comparison, money shouldn’t be the only point of comparison. In fact, once you surpass a certain threshold, money’s incremental importance might drop to zero.

As for what Emily thought maybe I shouldn’t have said, it’s the idea that our biggest competitor is the status quo. After all, if nobody ever sells us anything, we lose. But one of the reasons why we have our business is a shared passion for helping small businesses stay independent and thrive – and more of them will do just that if they just stay in the family (acknowledging, you know, circumstances).

What’s more, the value proposition of not transacting is pretty attractive. There are no disruptions to operations, no conflicts of interest, and no taxes. Did I mention no taxes?

But we know well that life is messy and that this isn’t always an option. That’s entropy for you, and it has a cost too.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

When Awesome Is Not Awesome

For my money my friend and mentor Bill Mann has the best background going on Twitter.

It’s an old, blurry photo, but yes, that’s him interviewing Elon Musk way back when and it captures the moment that he said something along the lines of this to the founder of Paypal, Tesla, and SpaceX:

When you watched the Falcon 1 launch but then explode over the Pacific, that was awesome, right?

Musk’s response, after this awkward locking of the eyes, went something like:

I was out of money. I had gotten divorced. And I had watched my life’s work blow up. So, no, Bill, it was not awesome.

I remember the rest of the interview being even more awkward. At least it was memorable.

Of course, SpaceX got its fourth launch right and has gone on to be a pretty spectacular success. I wonder if you asked Musk today if all of those development pains had been awesome (maybe Bill could have phrased it better), with the benefit of hindsight, he might say yes. After all, very few people are ever entrusted with the resources to do something so daring, and look, he probably doesn’t get to where he is today absent that failure.

But few challenges feel awesome when you’re in them even if they turn out to be just that. For example, if someone said to me in 2020, “Hey, remember that time during Covid when you thought several of your businesses might run out of money. That was awesome, right?” I would probably respond just as Musk did. Because no, it did not feel awesome.

Upon further reflection, seeing what some of our businesses did to stay the course and learn from the circumstances to make lasting improvements to their operations, there was a lot of awesome work that was done even if we didn’t know it at the time. In other words, we were winning when it felt like we were losing.

On the flip side, it’s possible for losing to feel like winning. We’ve seen this when the initial dopamine hit of winning a big contract gives way to realization that we may be unable to profitably fulfill it. Or there’s this sentiment from a Phoenix Open official after Sam Ryder’s ace on the famous 16th hole lead to a hurricane of beer cans being thrown from the crowd, hitting golfers and officials:

In neverending games, and enterprise is certainly one of those, you’re never too far ahead or behind, are always one breakthrough or pitfall away from a sea change in outlook, and can’t take credit or blame personally. The best advice I’ve heard for coping with that reality is to “stay medium.” I also like to think we are all works in progress. But I’m also fine with Mr. Musk for being touchy about Bill’s comment back then given the circumstances.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Read These Next

If you saw the Permanent Equity Christmas video then you know that I am considered ‘round these parts to be the “Chair of the Matt Levine Fan Club.” And I’ll cop to that. Whenever anyone asks me what they should read, I tell them to subscribe to his Money Stuff newsletter. And whenever anyone asks what I’m laughing about, I usually end up reading aloud to them a paragraph from that day’s column whether they like it or not.

So if you’re not subscribed to Money Stuff, do it. It’s not only entertaining, but the best free finance class you’ll find. We’ll also have a lot more in common and a lot more to talk about when you attend Capital Camp.

As for other things I read daily and recommend (because occasionally I’m asked):

The Wall Street Journal (for news and the crossword).

A leading paper from a different foreign city (for a different perspective).

SEC enforcement action announcements (because one can learn a lot from financial frauds).

SSRN’s Decision Science research paper feed (for occasional strokes of brilliance).

The mid-Missouri 10-day weather forecast (because it’s all we ever talk about).

Have a great weekend.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

It’s Not You, It’s Base Rates

One of my favorite things to do is nothing. This is a passion that dates all the way back to 2007 when I read a study that found that the optimal strategy for a soccer goalkeeper to stop a penalty kick is to just stand there. Not dive, not jump…just stay in the middle of the net.

So that’s why I found myself nodding along with this story about Dr. Bent Flyvbjerg and his research into how often attempts to do big things go awry:

His seminal work on big projects can be distilled into three pitiful numbers:

47.9% are delivered on budget.

8.5% are delivered on budget and on time.

0.5% are delivered on budget, on time and with the projected benefits.

It’s brutal enough that 99.5% miss the mark in one way or another. But even those stats are misleading. The outcomes are bleaker than they look. Dr. Flyvbjerg has found that the complexity, novelty and difficulty of megaprojects heighten their risk and leave them unusually vulnerable to extreme outcomes.

“You shouldn’t expect that they will go bad,” he says. “You should expect that quite a large percentage will go disastrously bad.”

Some people who work with me call me a pessimist, but the fact of the matter is that I’m a slave to base rates. This is the idea that the likelihood of you being able to do something is equal to the number of times that thing has actually been accomplished. In other words, if you’re planning a big project, you should expect that there is a 0.5% chance that it goes according to plan.

Of course, not doing anything ever isn’t really practical. But one can try to traffic only in no-brainers and in such a way that when that no-brainer inevitably goes off the rails, it doesn’t cost you the shirt off your back.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

The Wrong Way to Profit

Years ago I was in Singapore visiting companies that stood to profit from the rise of the Asian consumer class. One was an operator of bakeries and restaurants that owned and operated several different concepts that they were planning to grow into China, Thailand, and other fast-growing emerging markets. It was a promising story and the fundamentals looked solid. Of note was the fact that gross profit margins had stayed relatively consistent despite rising ingredient costs, a sign – I thought – of the company’s pricing power.

Meeting with management I brought this up and asked about it. They were quick to point out that they weren’t raising prices. Indeed, they didn’t think their target consumers would tolerate regular price increases. Instead, they said, they had surreptitiously been shrinking portions while keeping prices the same, and they seemed to think that was a very clever strategy (and one that’s popping up again in today’s inflationary environment).

Ultimately the math of shrinking portions versus raising prices works out the same way, but one strategy is much more sustainable than the other (eventually the customer will notice how tiny their cupcake got). What’s more, while the idea of passing on price increases may seem untenable, if a business is able to do so successfully, it’s a sign of how important its product or service has become to its customers. And if it’s not, it’s an indicator that you need to work on your core offering, not your pricing strategy.

As for the company in question, it’s since gone private without ever creating much value for shareholders. That’s because, over the long run, gimmicks like portion shrinking don’t create sustainable value. That only happens when your customer’s business is so well-earned that price is not the main reason that customer works with you.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Why AI Can’t Beat the Market

I thought this was funny: “We Asked ChatGPT to Make a Market-Beating ETF. Here’s What Happened.”

One of the reasons I got out of professional public markets investing was the fact that lots of technology – including artificial intelligence – was being thrown at the stock market in the neverending quest for outperformance. Interestingly, though, I don’t think such advances make it likely for someone to achieve better returns for the same reason that ChatGPT wasn’t able to design a market-beating portfolio. Rather, I think such things make the market much, much more efficient and therefore decrease the probability that anyone anywhere is likely to earn an outlier return.

That’s because there is no optimal investment strategy. Instead an investment strategy that works works only in the context of all of the other investment strategies going on around it. If everyone has trained algorithms to look for great companies based on certain quality factors, then those stocks will necessarily be expensive and that will definitionally be a bad investment strategy. If, on the other hand, no one wants to buy small private businesses, then those businesses will likely be cheap and that might be a strategy that earns good returns. The rub is that those things won’t be true forever. When people see others earning good returns on small private businesses, they will look there and that will become a bad investment strategy and when they stop buying great public companies, that will become a good investment strategy.

That’s why you want to be idiosyncratic; to zig when others zag.

AI, I think, is trained on data, so it does fantastically in areas when truths are immutable. Investing is anything but. The only things that consistently work when it comes to capital allocation are pragmatism and patience.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

What Happens After You Die

One question I wrestle with is “What happens after I die?” No, not in the metaphysical sense (though there is that), but in the estate planning and how will the people I’m close to who outlive me carry on in my absence senses.

Key to this is the question of how much control can and should one have from beyond the grave. When it comes to assets, for example, one can do everything from just leave them to others with no strings attached to put them in a trust with a mandate and a governing board with a smorgasbord of rules.

As for how people will carry on, there’s not much you can do. That’s troubling because how one decides to handle asset transfer depends on how the people stewarding those assets are likely to act. (And that’s true for giving it all away as well. Like families, not-for-profits are also complicated organizations full of people and who knows what the world’s most critical problems might be in the future?)

I believe pretty strongly that one’s overarching aim in life and work is to always be making one’s self obsolete. This means that others are learning what you do and then learning to do it better in such a way that you don’t have to do it anymore. If you do this well, then estate planning is easy. Leave everything with no strings attached and trust that others will do what you would have done – and perhaps better – if you hadn’t passed.

That’s quite the trust fall, though, and attorneys that I’ve mentioned the approach to think it’s crazy (acknowledging that they have an incentive to create complicated legal documents).

Yet I don’t know that I can top it. There are always unknown unknowns and unintended consequences. If I make a mistake designing a plan on the front end (and there’s a 100% chance that I will, given the circumstances), I can’t help fix it when I’m dead. All I can control is the effort I put in now to build relationships with the people around me, so maybe I should just do the best I can at that and the chips will fall where they fall.

Related to this is the observation that great businesses, after experiencing peak greatness when typically the founder is still in charge, seem to get less great the farther away in time they get from their founding and after the founder steps away. That’s weird because it seems like a great business should attract great people that would make the business greater. But approaches change over time and things are inevitably lost in hand-offs and transitions.

That would augur for lots of documentation and codification, and while that would make the lawyers happy, I don’t know that it’s a good answer either.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

More CIMple Truths

As always, we have empathy for the analysts at investment banks tasked with putting together lengthy decks about small private businesses (aka Confidential Information Memorandums or CIMs for those not in the know). Information is often incomplete or missing altogether, there are skeletons in the closet, and the people approving your work probably don’t appreciate how difficult it is to make a color pop.

That said, we occasionally see some things that make us scratch our heads. In no particular order…

Strange, unqualified explanations…

Of course it did.

Hard-hitting analysis…

More people, you say?

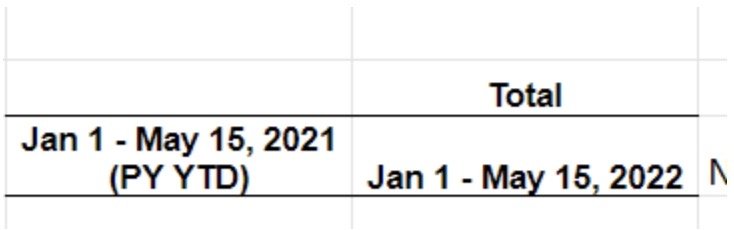

Cutting off the numbers on an oddly specific date…

They’ll tell you what happened on May 16 after you submit an LOI. Have a great weekend.

— By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Permanent Equity’s Secret Formula

I got an email the other day from someone who was raising capital. When I asked about information he said, “We’ve been working with Bain, so have quite a bit of content.”

And so they did. The data room we were given access to was chock full of charts and graphs and decks.

Now, at Permanent Equity, we are notable in that we go out of our way to tell the leaders of our portfolio companies that they don’t have to waste time on those things. We don’t do quarterly board meetings, and we certainly don’t want someone with competing priorities spending hours designing PowerPoint animations. The reasoning is that that frees them up to focus more time on items that will actually move the needle.

But is there a middle ground?

I spent a great deal of time recently trying to distill what Permanent Equity does into a mathematical equation. (After all, if something can’t be written as a formula in Excel does it actually exist?) Here’s what I came up with:

In other words, our success as an organization depends on raising capital, investing it well at scale, and making gradual improvements in those investments over a long period of time. That may seem self-evident, but distilling it to that formula took a while. Was the time worth it to now have a graphic for an investor deck? I think so. It was a clarifying process, and now I can explain what we do in a sentence.

See, sometimes there’s value in going through the motions. I thought about this the other day when I listened to Brent’s conversation with Shane Parrish and Shane remarked on the difference between ritual and discipline, saying that you need motivation to do something three days a week, but not to do the same thing seven days a week. The reason is that the latter is a ritual, not a choice.

In college I took a writing class where the only assignment was to write 1,000 words by 9am each morning and then walk them over to the English department and drop them in the professor’s inbox. It didn’t matter what you wrote, you could write the word “word” over and over 1,000 times, it just mattered that you did it.

At the time I thought the assignment was nonsense. I appreciate now that he was helping us realize that if you wanted to write, writing was not a choice. And in doing so much writing, you often started writing something that wasn’t half bad.

That’s the paradox for me of repetitive processes and things like investors decks and standing meetings. They’re not always valuable, but in doing them, value is often created. So how much time is the right amount of time to spend on them? I have no idea.

– By Tim Hanson