Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions delivered to your inbox.

People Who Worked For Me

There are inside jokes and there are inside jokes by which I mean jokes that are only funny to the person telling them and my relentless trolling of Morgan Housel for a retweet certainly falls into the latter category. (But it did make me laugh.)

If you don’t know Morgan, he is today a best-selling author, partner at the Collaborative Fund, and an in-demand speaker on behavioral finance (who we just happen to have a podcast conversation with out today). Plus, he’s a great dude. What’s also true is that at one point in a past life he worked for me.

Morgan’s always been a great writer, but he’s never been strong on change and he and I had a lot of conversations before he decided to move on to something next. That probably seemed like a net negative for the organization we both worked for at the time, but it turned out to be a great move for everyone involved. No one doesn’t benefit from others achieving great things. And now instead of managing him, I get to free ride on his 450 thousand followers.

Lesser-known than Morgan, but still great, is Michele Hansen (who has fewer Twitter followers than Morgan, but still more than me). She, too, worked for me in a past life while also founding and bootstrapping her own software company, Geocodio. She’s since gone on to run that company full-time while also finding time to write a book and host a podcast (Morgan has a new podcast too).

I’m plugging my friends and former direct reports here because I’m proud. I think the best measure of anyone is what the people you might be helpful to go on to do next. And while it’s insanely egotistical of me to believe I had anything to do with any of this, Morgan did send me an inscribed copy of The Psychology of Money that I keep on my desk and Michele did send me a Geocodio sticker that I put on my laptop because both inspire me and remind me when I see them of what matters when it comes to people.

P.S. Permanent Equity’s investing team is hiring. Click here for the details.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Apple Watch Psychopaths

Luckily, I live out in the country because otherwise I would be embarrassed by my neighbors seeing me sprint down my driveway at 9pm risking life and limb because my Apple Watch told me I could still do it and burn the 40 calories left to hit my Move goal.

Yes, I’m a psychopath. Does anyone else have this kind of dysfunctional relationship with their Apple Watch?

The answer has to be “Yes,” right? Because everybody has them. I look around now and see so many square faces on wrists despite the fact that it was viewed as a failed product upon its release. And it should have been, if it didn’t become so darn useful. Absent its judginess, it’s a no-brainer. That said, everyday I think about going back to the Timex Ironman I keep in my bedside table.

But I digress…

Which brings us to metrics, which are both the most important and most dangerous concept to introduce to any business…or really any group of people. If you have them and you understand them and you work towards them, metrics can be unlocking and important. But if you try to achieve them at any cost without regard to nuance, they can be your undoing…fast. To bring this all full circle, yes, it’s frustrating to come up short of an arbitrary but well-intentioned goal, but do those last 40 calories really matter in the scheme of things and should I be out in the pitch black with a headlamp instead of helping put my kids to bed?

But I digress again…

When it comes to metrics, three things matter: (1) What; (2) When; and (3) How.

What is the variable you are measuring. Make sure these are items that matter and that are leading indicators i.e., predictive and not lagging indicators i.e., reactive.

When is the time period over which you are measuring your What. Does an hour matter? A day? A week? A month? A quarter? A year? Make sure what you are measuring is calibrated with when you are measuring it and that the two together provide meaningful information.

And finally How are you achieving the What over the When? As Mark notes, if you’re measuring a rate, make sure you’re also measuring a volume of throughput. And if you’re measuring volume, make sure you’re almost measuring a rate of quality. Moreover, ask if what you’re doing makes you proud? And is it sustainable or does it carry hidden costs i.e., does it make you want to go back to your Timex Ironman?

These are also important questions even if your What and your When are spot on.

P.S. Permanent Equity’s investing team is hiring. Click here for the details.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Where Did the Money Come From?

Emily (our MD) sent me this cautionary tale about a guy who won an auction for the famous (because it’s a triangle!) Flatiron Building in New York City and then couldn’t even produce his $19 million deposit. You would have thought somebody would have asked for proof of funds from any potential bidder beforehand because now a lot of work has been done and no one is any closer to closing a deal.

If you remember your risks, this is counterparty risk, or “the risk that the other side of the trade will fail to perform.” The obvious lesson is that before doing a deal, make sure the other side has the money.

But I also think counterparty risk is more than just black or white. You not only want to know if your counterparty has the money, but also where he/she/they got the money from. Because while the source of capital may not be what determines whether it’s there or not, it absolutely will determine how it behaves. And if you’re going to be stuck with your counterparty for any length of time after a transaction closes, that matters.

Here’s a hypothetical…

Let’s say you were Twitter. Would you have rather taken an investment from Warren Buffett or Elon Musk? If you don’t know what you know now about how Musk has run Twitter since his investment, I actually think the answer to this question is a pretty close call. Despite Buffett’s reputation, it’s unlikely he could have helped the company. He is typically hands-off and doesn’t cop to having much knowledge about technology whereas Musk is (was?) one of the foremost technologists on the planet.

And – hot take – I actually think Musk could have been (and may turn out to be) a pretty great owner of Twitter. What tripped him up was the fact that he overpaid for the company using high interest rate debt and personal wealth tied to leveraged, highly volatile stock. This is not high quality capital. Instead, it’s expensive and short-term and what has happened at Twitter since Musk’s investment – the cost cutting, aggressive monetization, etc. – is always what happens when a deal is closed using expensive, short-term capital. In other words, the root problem isn’t necessarily who provided the money but where the money came from.

We teach kids that it’s rude to ask anyone where they got their money from, but (1) it’s a really important question and (2) anyone who actually has high quality capital should be proud to tell you about it.

P.S. Permanent Equity’s investing team is hiring. Click here for the details.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

And More CIMple Truths

As always, we have empathy for the analysts at investment banks tasked with putting together lengthy decks about small private businesses (aka Confidential Information Memorandums or CIMs). Information is often incomplete or missing altogether, there are skeletons in the closet, and the people approving your work probably don’t appreciate how difficult it is to make a color pop.

That said, we occasionally see some things that make us scratch our heads. In no particular order…

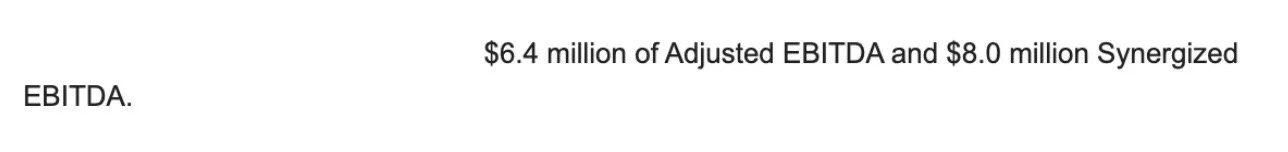

Fake numbers and made-up words

Tremendous synergy.

Announcements that say nothing

Congratulations to someone for something!

Needless hedging

We didn’t do that already?

Numbers that don’t quite add up

Wait, what?

Have a great weekend and shoutout to Danny Coffeepot for his help on today’s Opinion.

P.S. Permanent Equity’s investing team is hiring. Click here for the details.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Who Holds the Float?

It turns out that David (our creative director) is passionate not only about high quality content, but also March Madness. This was probably helped by the fact that his alma mater Mizzou made the tournament as a frisky 7 seed (although the high variance team flamed out in the second round), but motives aside it was good for the office vibe. We made tee shirts, ordered wings, had contests, and watched the games. Of course, he also administered a bracket challenge. It was $10 to enter and he required that you pay upfront (the Challenge, I might add, was won by my daughter who picked San Diego State to win it all).

Ever the imp, I poked him on Slack. “Why do you get to hold the float,” I asked?

“Because it’s not my first rodeo,” he replied. “Coordinating who owes what to who at the end is a mess. Pay to play is the way.”

Which is completely a fair point, but I can never leave well enough alone. Now, for the rest of this exchange to make sense, you have to know two details:

David briefly way back when dabbled in speculating on obscure cryptocurrencies, including Polkadot.

When I think something is funny, I never let it die.

Two observations. First, it’s amazing to me that “pulling out to fiat” is part of our vernacular now. Second, even in this small example, when you pay or when you get paid and what happens to the money in between those events matters.

The term for this is “float,” and it’s how Warren Buffett built his empire. Here he is writing in his 2009 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders:

He estimated that year that Berkshire’s insurance operations provided him with $62 billion of other people’s money to play with. Not bad work if you can get it, particularly if you have the investing acumen of Warren Buffett and can put that money to work making more money.

What’s the takeaway?

If you run anything from a small NCAA office pool to a multinational conglomerate, think carefully about when money moves and who gets to hold the float. If it’s not you, why not? If you’re floating other people, why? And how might you stop?

But if you do get the float, crucially don’t do something stupid with it because you’ll have to give it back eventually. Or “pull it out to fiat” as I guess the kids say.

P.S. Permanent Equity’s investing team is hiring. Click here for the details.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Perform, Don’t Perform, But Also Perform

After I wrote about Permanent Equity’s secret formula, I received an email reply (which I love…if you reply to this email it goes directly to me) from someone who said “I’ve been involved with companies for more than 25 years and keep getting caught up in the ‘what people think you need to do or want to see’ perspective.”

I think this was mostly a reaction to the idea that we don’t require our portfolio company leadership to be good at PowerPoint animations and that one shouldn’t spend time on activities that don’t actually move the needle. But it’s also true that it doesn’t hurt to be good at PowerPoint animations.

What am I talking about?

I made the observation on Twitter that back when I ran an investment team, the ideas from extroverts were overrepresented in our portfolio vis a vis the ideas from introverts. The reason was we had a process that required analysts to present their ideas to a group and introverts were not as good at that as extroverts. And that wasn’t fair to the introverts or a very good process, which I think is a point that stands.

But SuperMugatu aka Dan McMurtrie (a very smart investor we know) responded “I agree with the virtue of what you’re saying but have been seriously burned by people with poor communication skills.” And he’s got a point too.

When I was first starting out as an investment analyst I was taken aside and told “Look, you’re not going to be judged by all of your ideas. You’re going to be judged by the ideas clients actually take action on. So, you have to always be selling.”

That’s why it can pay to be good at PowerPoint animations. They’re a means to convincing others that your ideas have merit. Yet it’s also true that if you’re always performing for others, you won’t have time to spend on efforts that actually generate good objective performance.

This can be thought of through the product/packaging paradigm. In order to be successful, you need a good product, but you also need to put that product in attractive packaging that is enticing to consumers. In other words objective performance and performative performance go hand in hand, but striking the right balance can be an ongoing challenge. If you tilt too far to the former without the latter, you’re the proverbial tree falling in the forest that no one hears. But if you’re the latter without the former, you’re, as they say in Texas, all hat, no cattle.

P.S. Permanent Equity’s investing team is hiring. Click here for the details.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

The Cause of and Solution to Life’s Problems

After I wrote about Growth, and Other People’s Money, I received a thoughtful note from @michaelnewt. He wrote:

OPM can be addictive. It changes behaviors and incentives…Mathematically it makes sense to go with the cheapest capital, but your write ups on OPM and Debt vs Equity are the reminders I needed to think deeper on the issue. There is more to choosing the best partner than simply what Excel tells us to do.

I joke that Excel is the cause of and solution to all of life’s problems. That joke is a riff on an old Simpsons episode that said the same thing about alcohol. And I’d argue that they are not dissimilar. In moderation, both are great, but if you let your life be run by spreadsheets or booze, well, you have a problem.

Keep in mind that I say this as someone who has a spreadsheet for everything.

Household budget? Spreadsheet. Son’s swim times? Spreadsheet. Distribution of wildflowers in a native Missouri wildflower meadow? Spreadsheet. But I have to remember that as much as I love a numerical safety net, data is a way to help you make decisions, not to make decisions for you.

In fact, I’d argue that one of the most dangerous situations you can find yourself in is one where “the numbers make sense.” If you’re falling back on the fact that the numbers make sense, then it may be the case that the sense doesn’t make sense. This, I think, is how people got lured by low interest rates to buy too much house in the mid-aughts or how a financial institution like Silicon Valley Bank got lured to buy long-dated slightly-higher interest rates treasuries more recently.

In both cases the numbers made sense, but the decisions turned out to be bad ones.

There’s a saying that numbers don’t lie, and that’s true. The learning, though, is that people can and do lie, both to themselves and to others, and often use numbers to do it.

P.S. Permanent Equity’s investing team is hiring. Click here for the details.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

How to Become a Good Investor

We recently launched a new program at Permanent Equity with the goal of hiring investment analysts for a predetermined period to help us increase our deal flow and help them become better investors. Here are the details of the program, but what I hope is most interesting is the idea that we intentionally didn’t overengineer the details and are interested in candidates with a broad range of backgrounds and experiences.

Not a CFA? Not a problem.

Never built a DCF model? We can teach you how to do that.

Don’t know what an Iron Condor is? I wish I didn’t either.

The reason for that is there is no clear cut expertise that makes someone a good investor. Math matters, sure, but so does temperament, curiosity, communication, salesmanship, confidence, humility, and so much more. Moreover, the way we do it, investing is a team sport, so it’s also important that you fit but also don’t in such ways that it makes our team stronger and more resilient.

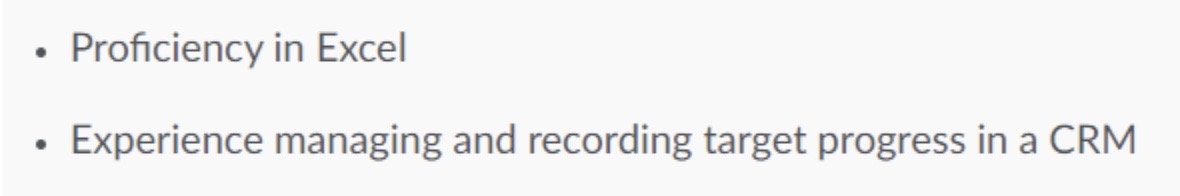

Finally, I’d add that I don’t even know that I’m wedded to some of the preferred qualities we listed. Are they preferred? Sure. But these two right here would have meant that a version of Past Me would not have been qualified for the job.

The point is that I think anyone can become a good investor regardless of where they’re starting from. The key is getting real reps and transparent feedback to find the approach that works for you. Those things are each easier said than done, of course, but I think we can offer both.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Read Your Own Emails

We were in a meeting the other day when I said something colossally stupid. The table called me on it, and I agreed.

What I’d proposed was an idea that would net a small gain for one of our portfolio companies at the risk of exposing our entire portfolio to loss. While it might have worked, that’s not ring-fencing, it’s inviting contagion. “It’s like I don’t even read my own emails,” I muttered later to myself.

And yet…

There’s a reason why “Do as I say, not as I do” is an aphorism. It’s often much easier to say something than actually do it. One example in sports is the football coach who punts when the entire team and the television commentators and all of the fans in the stadium know they should go for it.

There are a lot of cognitive biases at work for why this can be the case, particularly in stressful situations. To combat them it’s important to have objective procedures in place such as checklists or manuals or reference guides to know when you are deviating from the standard you set when weren’t stressed. But even more important, particularly if you’re in a position in leadership, is to make sure you empower everyone around you to call this out when it happens.

After all, one of the most important things someone can do for you is tell you you’re wrong and be right.

Have a great weekend.

P.S. Permanent Equity’s investing team is hiring. Click here for the details.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Pistachios, Six Flags, and Assumptions

My daughter and I were getting set to make the 90 minute drive home from St. Louis after one of her soccer games when we decided to stop at a convenience store to get a road snack. She picked out chips and I, trying to be slightly healthier, grabbed pistachios. We got back in the car and on the road and it was then that I noticed my mistake: the pistachios weren’t shelled. Since there’s no way to shell pistachios and drive (responsibly) on the interstate simultaneously, my road snack was worthless.

“I was wondering how you thought you were going to do that,” she smiled.

Thankfully she shelled my pistachios for me after she finished her chips, so all was not lost.

Now this is admittedly smaller stakes stuff (though never underestimate h-anger), but it’s illustrative of the fact that game-changing mistakes can be made when you take small things for granted (leaving aside what me assuming all pistachios are shelled says about my own moral degradation).

Here’s a related example…

Mark (our COO) told me about a time when he was a kid and visited Six Flags with his family. When they arrived, the computers were down, so the park couldn’t accept credit cards. Thankfully, Mark’s dad Paul is old school and carries cash. He was able to pay for everyone’s tickets out of pocket even as those trying to pay with plastic were out of luck, so the family got to enjoy the park crowd-free for a few hours until the computers came back online.

That’s not an example of how taking something for granted led to a mistake, but rather of how not taking something for granted can create a massive advantage if everyone else takes it for granted. No one except Mark’s dad Paul thought they might need cash at Six Flags and 99.9% of the time you don’t. But the 0.1% of the time you do, well, that’s World’s Best Dad stuff.

So a very interesting question to ask is “What do I take for granted and what might it look like if I didn’t?”

Back when I worked in public equities I took it for granted that given the liquidity of public markets, I would always be able to buy and sell investments. Now that I don’t, my behavior as an investor is different, particularly when it comes to underwriting risk and spending time on relationship building and origination. This is not to say that Current Me would have done Past Me’s job better, but rather that Past Me might have benefited from thinking a little bit more like Current Me on this topic.

Businesses can take things for granted as well, such as employees staying healthy, customers abiding by payment terms, and so on. Yet the real world inevitably intervenes. Now, in order to be efficient it’s not necessarily to always be examining all of your underlying assumptions, but it is worthwhile to list them from time to time and ask what you might do differently if you didn’t take them for granted.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

There’s a Small Chicken Shortage

I did not expect to open The Wall Street Journal the other day and see the headline “KFC, Other Chains Hunt for Elusive 4-Pound Chicken,” but there it was. Apparently due to the skyrocketing popularity of spicy chicken sandwiches (and they are delicious; shoutout Hattie B’s) small-breast meat is in high demand while chicken farmers prefer to produce larger, meatier, more profitable birds.

The market should correct for some of this but among smaller businesses there’s a concern that “in a few years the large fast-food chicken chains will hog the tight supply.” And it’s a valid concern. In fact, one of the biggest risks for any small business is that a larger, better resourced competitor changes the rules of the game because any changes will have a disproportionate impact on the small business.

A good summary of this reality comes from a 1981 Harvard Business Review article that I discovered back before I took a job at Permanent Equity when I was reading around trying to get a lay of the small business landscape. “A Small Business Is Not a Little Big Business” makes the compelling case (and I’ve found it to be largely true) that small businesses, through no fault of their own, suffer from resource poverty and therefore “external forces tend to have more impact on small businesses than on large businesses” The authors warn further that “small businesses can seldom survive mistakes or misjudgments” (also true), which is why when you meet small business owners liquidity, and not ROI, is paramount.

This is where higher prices for small chickens, or a lack of supply, could be devastating for the not Chick-fil-As of the world. That’s because direct costs, such as chicken prices, are likely to be a greater percentage of total expenses for a small business than a large one. Moreover, a higher percentage of operating expenses at a small business are likely to be fixed or difficult to cut because they have fewer employees, smaller marketing budgets, etc. Finally, if a small business has to do something like borrow to buy its raw materials, rising input costs and rising interest rates can combine to wipe out any remaining profits pretty fast and there is likely less ballast on the balance sheet to sustain them.

Or as HBR put it, the short-term variances during the year at a big business are relatively small compared to the overall result so their financial statements describe a system in approximate equilibrium. Small businesses, on the other hand, are “seldom in equilibrium, or even near it.”

When you don’t have a steady state, any adversity can be major adversity if you’re not prepared for it with a lot of room for error.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

How the Muppets Ended Up Singing Nirvana

At the risk of dating myself, “Smells Like Teen Spirit" is one of the great songs ever. If I owned the rights to it, I’d consider it closer to the irreplaceable end of the asset spectrum and not cheapen it by letting anyone else use it for anything other than rocking out.

And yet here on the internet are the The Muppets doing a pretty horrendous barbershop quartet version of it…

And here’s another (not as bad but not as good as the original) version at the opening of Disney + Marvel’s Black Widow film…

What happened was that Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain’s estate sold some of its voting rights in matters like these for a tidy sum of money to an entity that’s more than happy to license rights for cash flow and the other original members of Nirvana voted along with that because they had diminished economic rights anyway (don’t fact check me, I read it on the internet). But at the end of the day, the asset was commercialized in a way that impaired the underlying value of the asset…maybe…

Irish playwright Samuel Beckett (he of Waiting for Godot fame) catches flack in some quarters for being notoriously strict from beyond the grave in his demands for how his plays are produced:

But I’m good with it even while acknowledging that other interpretations might also be valuable:

And yet ownership matters:

If you own something of incredible, irreplaceable value, commercializing it to be marginalized in a Muppets movie (and I love the Muppets) seems shortsighted. So, too, however, does thinking that your way will always be the right way and that something you created can never be improved upon.

There’s a world where “Smells Like Teen Spirit” should have never been sold to be sung by The Muppets. But there’s another where a new take on Waiting for Godot is a global blockbuster that enhances the value of the original.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

When You Should Know Everything

This recent piece (“Ignorance Really is Bliss When It Comes to Investing”) in The Wall Street Journal is mostly spot on. Its conclusion? That knowing more doesn’t help you make better investing decisions.

Back when I ran a team of public equity analysts, we had a rule that no financial model could run longer than 20 rows in Excel. The reason? Limiting your inputs forced you to boil down your thesis to the metrics that really mattered.

But there’s nuance here in that ignoring the fine print is really only something you should do when you have asymmetric upside i.e., your potential gains are uncapped but your losses stop at zero. Because if you have losses that could generate additional liability, then you should absolutely read the fine print. The reason is that if you don’t dig into everything you could inadvertently wander into uncapped pain.

Here’s a real life example. We were recently looking at a company where the core business looked strong. But we discovered in the course of asking a lot of questions that its warehouse abutted a property that was a contamination site. Moreover, they’d never had a phase 1 let alone a phase 2 environmental assessment done on the property yet the lease held the tenant liable for remediating any issues caused by said tenant. So if we took on that lease without knowing what was already in the ground on that property we could end up on the hook for a multiyear multimillion-dollar clean-up.

Was any of this germane to the core investment thesis? Of course not. But could it turn a promising potential investment into a massive loss. Of course it could.

This is among the reasons we have Taylor (our CLO) on staff and why his diligence request spreadsheets run way longer than 20 rows.

See, when you’re in charge of upside, you need to focus on what matters. But if you’re accountable for the downside, you need to know everything. So who carries the day? We should all always be in charge of and accountable for everything but still, we come from where we come from and so that’s always the subject for debate.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Why More Banks Will Fail

A lot has been written about Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and the other financial institutions that failed or almost failed recently. People understandably want to know why that happened and who was responsible. And as I said on a recent podcast with Nikki (our CFO) and David (our creative director), there is a lot of culpability to go around.

My intent is not to rehash any of that here as better explainers have already been written. Instead it’s to build on an exchange that Emily and I had on Slack and that I tweeted about:

One of my favorite memos is the Lin Wells memo that Donald Rumsfeld shared with then President Bush in April 2001 ahead of the Quadrennial Defense Review. The point of the memo is that it’s hard to predict the future and that big changes can happen in short periods of time, so plans should be adaptable and not assume that anything will stay the same. The timing of the memo is evidence of that as well as five months later September 11th happened and the world changed again.

What does this have to do with banks failing?

A common thread across the banks that failed is that they assumed (1) that interest rates would stay low and (2) that depositors wouldn’t all ask for their money back at the same time. Assumption (1) was naive on its face, but to be fair rates until recently had hovered near zero for almost 15 years. And if you can’t assume (2), well, you can’t reasonably operate as a bank. So I understand why mistakes were made.

Regulators won’t want to read this but regulation is inherently narcissistic. It means that you think you reasonably know what might happen before it does and can write rules to prevent it. But as the Wells memo demonstrates, we often don’t know anything about even really big things before they happen. But to Emily’s point, rulemakers can’t also be constantly reactionary, deciding what’s allowed and what’s not ex post facto. That’s the Calvinball approach (shoutout Bill Watterson) and it wouldn’t work either!

How can these ideas hang together? The answer is they don’t. And that’s why, whether now or in the future, more banks will fail and other bad things will happen because we didn’t know what to prepare for.

Have a great weekend.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

The Circle of Sadness

One thing that a lot of people don’t know about me is that I cry during pretty much every Pixar film. In fact, I made the mistake of watching Up for the first time on a flight to Germany and was such a weepy mess just a few minutes in that the stoic Lufthansa flight attendants felt compelled to come check on me. I’m not sure why I’m sharing this other than this is the background you need to understand why one of the best ways to think about risk management comes from Inside Out.

If you don’t know the film, the premise is that all of us are run by competing emotions with distinct personalities inside our head with each of them “driving” at different times. When Joy’s in charge, for example, we’re happy. When Anger is, we’re mad.

The plot of the movie is that an 11-year-old girl moves from Minnesota to California and in doing so starts to be driven more and more by Sadness (which is what happens when one leaves the Midwest). Joy, however, doesn’t want to see that happen and does everything she can to stop Sadness from taking over, but in doing so sows chaos. It’s great entertainment.

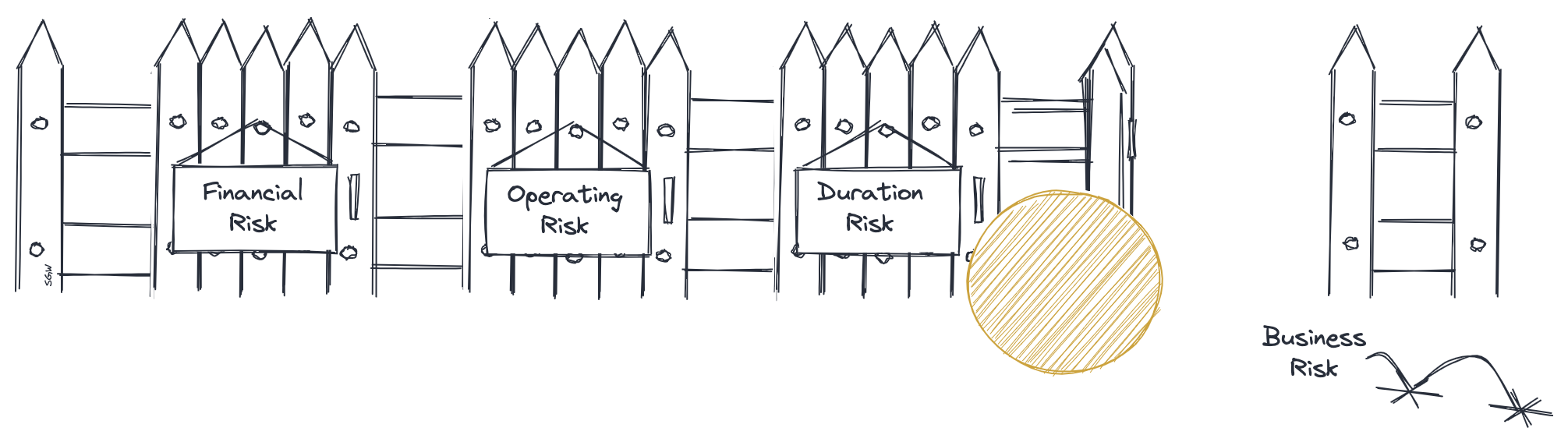

One iconic scene is when Joy draws a circle around Sadness and says that her job is to make sure all of the sadness stays inside of it. And that’s precisely how to think about risk.

See, when you’re taking risk, whether business or operating or investment or duration or whatever, you’re not going to walk away unscathed 100% of the time. What’s more, that arguably shouldn’t even be a goal because if you’re always right, it probably means that you are not taking enough risk. But if you know that you are going to be wrong or unlucky, then what’s critical is to make sure when you are, the consequences don’t overwhelm you.

For example, if you have a portfolio of real estate, it probably all shouldn’t be on the beach in Miami because if you’re wrong about hurricane risk, then you’re going to have a real problem. Or if you have a handful of businesses, they probably shouldn’t be guaranteeing one another’s loans because if one goes down it’s going to take the rest of them with it. Or if you have operating funds and emergency funds, you might not keep them in the same account at the same bank, just in case. Because if that bank fails, you’d lose access to your emergency funds at exactly the time you need them.

The term for this in high finance is ring-fencing, but ring-fencing applies everywhere. It’s the deliberate practice of acknowledging that bad things happen and therefore organizing yourself in such a way that when they do, it’s not game over.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Are We Effed?

Brent (our founder) recently sent me a Twitter thread from someone who declared that we are effed. He knew a software developer in Pakistan who used ChatGPT 4 to study a hundred thousand Shopify sellers and then email three thousand of them each a plan for a unique custom app that it ideated that the software firm might build for them to improve their business. It was a massive, audacious cold email campaign and apparently it worked. The response rate was off the charts and in order to handle the volume, he also had ChatGPT 4 respond to the responses.

Minds were blown… The AI learned about the target company, learned about the capabilities of the software firm, brainstormed reasonably good ideas at scale, and then credibly interacted with other humans on specific topics.

After he sent me the thread Brent wanted to know (1) how we might employ similar capabilities to benefit our business and (2) what the endgame of widespread adoption of this technology might be.

With regards to (1) the answer is really any detail-oriented, repetitive task. For example, ChatGPT could be trained to look at company financials, identify red flags, and engage in initial due diligence over email, handling both initial questions and follow-ups, particularly if you helped it figure out what to look for. Now, you probably wouldn’t want it doing these things unsupervised, but if it could get you 90% of the way there, that would result in a significant efficiency level up.

Which brings us to (2)…

If you work online, you are about to get flooded with AI-generated solicitations. In fact, you probably already are (and Elon Musk already admitted as such). In fact, I kinda sorta suspect based on the tone that the original Twitter thread Brent sent me was generated by AI as well (and how meta is that?).

Being online is already a terrible place to be. Studies show that it’s bad for mental health and that it’s contributing to polarization. Moreover, my own experience is that the signal to noise ratio is deteriorating.

So what’s it going to be like when infinite bots are generating infinite content?

This is the dystopian turn our conversation took, but it ended on an optimistic note. In this world that may be nigh, the value of two very human qualities should skyrocket: judgment and authenticity. Judgment because in a world of infinite content it is going to be very valuable to be able to differentiate the good from the bad and the high potential from the low. Authenticity because in a world of infinite content the only content that anyone will respond to will be words that really resonate.

What’s more, are we going to become cynical and skeptical about who we think we’re interacting with? If you think it’s a bot on the other side, how likely might you be to engage? If very, what are you going to do?

We thought about that and wondered if it might drive people to deepen human, in-person relationships. You’ll reach out to the people you know and want to talk with them directly. Workers are already returning to the office in droves following a few years of unsatisfying remote work that many initially thought would be a boon for productivity and finding that they like it. It turns out we’re social creatures.

So whatever else happens with AI, if it puts us back in real world contact with one another, that would be a real benefit. And an improvement. And perhaps help us not be effed. Because judgment and authenticity matter.

P.S. This was written by ChatGPT 4.

P.P.S. Just kidding…but how might you tell?

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Growth, and Other People’s Money

I saw the financials recently of a relatively small business that aspires to be a premium global consumer brand. Not only that, but it’s made some progress towards achieving that goal and may ultimately get there. But what was interesting to me was the trajectory of the company’s growth and what that might portend.

Rewind three years and this was a company that was growing ~25% annually with gross margins around 50% – well above the industry average. That’s a real success story: good growth with premium pricing. Those numbers suggest that there was a there there that’s really resonating with consumers.

At that time the company decided to take on outside capital so (1) the founder could take some chips off the table and (2) the company could invest in its balance sheet. That capital came from one of the big well-known firms through a fund that had less than 5 years left on its fund life.

What do you think happened next?

When I think about trying to build a valuable brand, I always think back to the time I met Brunello Cucinelli at an investment conference in Paris. His namesake fashion house was newly public at the time and he was trying to set expectations in the market. He told everyone at that conference that his company would never grow too fast, that he would aspire to gracious growth, and that he would protect quality, reputation, and margins at all costs. That, I suppose, is how you sell $2,495 cargo pants.

What an approach like this means for investors is that the returns in any individual year will never be extraordinary, but that over a lifetime of compounding, something of extraordinary value will be built. Would you invest? Obviously it depends on your time horizon and whether or not it matches Mr. Cucinelli’s.

Back to our aspirational consumer brand…

With a new investor that wanted to be out in less than 5 years, they mashed the pedal down on growth. Sales almost doubled the first year, and then doubled again. But gross margins dropped 1,200 basis points, profitability evaporated, and the business started to consume cash as inventory piled up on the balance sheet. Yes, you can achieve incredible temporary growth if you’re in-stock and slash prices.

And then the investor was back out in the marketplace trying to sell its stake at a valuation of 3x sales, believing it had earned 5x on its investment in just a few years.

Are you a buyer?

Running the numbers I could back into their valuation by assuming that the company could sustain its recent pace of growth while margins and the amount of inventory the company carried on its balance sheet reverted to previous levels. But that seemed to me an impossibility. Margin is one of the hardest metrics to recover in the marketplace. If you built your share on lower prices, your customer is not likely to stay with you when you raise them and raising prices is not something you can do when you have elevated levels of seasonal inventory. So what happens next is anybody’s guess.

My experience is that every company faces inflection points and that what happens next depends on what the organization is optimizing for. Very often what the organization decides to optimize for ends up matching what its investors are optimizing for. And while everyone says they’re a “long-term” investor, people define that term differently. This is why one should figure that out before taking someone else’s money and choose carefully before you do.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Have Fun writing Memos

When I was a kid I played baseball and my favorite game days were when we got to play a double header. I think that was because it gave me an excuse, if not a reason, to spend the entire day doing something I truly enjoyed.

I think about this whenever I start to draft an investment memo. See, we’ve iterated into a process at Permanent Equity whereby the investing team circulates a full-blown analysis to the diligence and operating teams before we start diligence. The reason is that we want everyone to understand what it is we think we are investing in and then empower anyone to throw a flag if they come across anything that runs counter to that thesis. That can be in the numbers, the people, the opportunities, or the risks.

But the point about fun is that that’s what I want to have as I write the memo. If it’s not fun to write about an investment, it’s not going to be fun to hold it for 27 years. Because if you’re not passionate about the numbers, the people, the opportunities, and the risks, it will be brutal to endure all of the volatility that will happen along the way.

The other week Mark and I went to visit a prospective partner. We spent a couple of hours together and at the end of it he said, “That was fun. You guys should have planned to stay for dinner.”

We replied half-jokingly, “Well, we give people a couple of hours first. And if that goes well, a day or two. And then we jump to 27 years.”

But it’s true that if you’re going to do something for a long time, you have to enjoy doing it. So even though it’s completely a non-financial question, it’s entirely credible to ask before making any kind of investment, “Is this going to be fun?”

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Everything You Need to Know About Risk

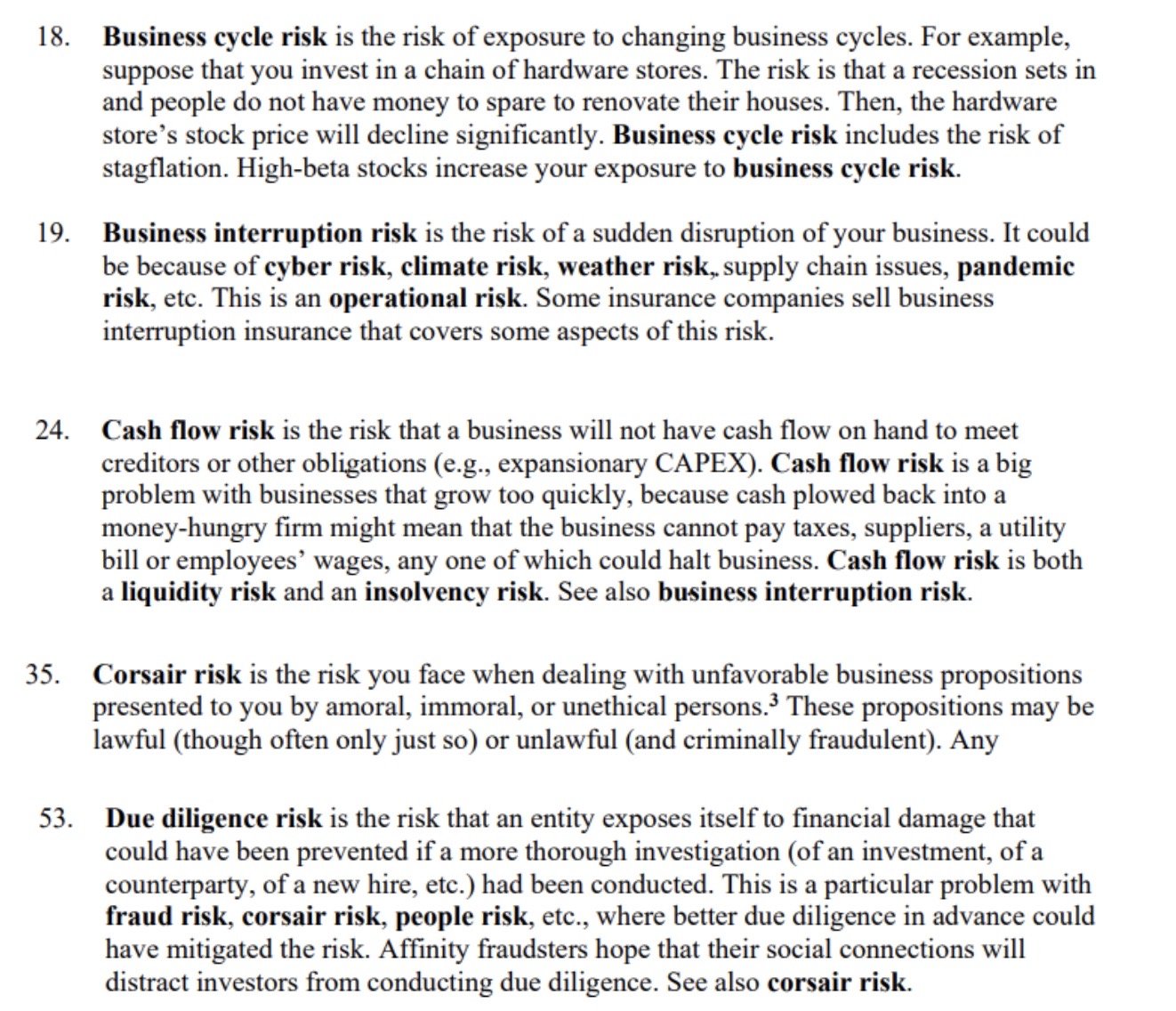

It’s not often that an academic research paper makes you laugh out loud, but that’s exactly what happened when I found this Easter egg inside of 150 Risks in Finance: An Alphabetical List of Definitions and Examples:

They appear to have a good sense of humor at the University of Otago. But they also know their risks, so I recommend you keep that link on hand as a handy reference guide.

There are also some exercises at the end where they propose scenarios and invite you to identify the inherent risks. I had fun reading those and figured it might be worthwhile to apply the framework to what we do…

Scenario: You have the opportunity to acquire a majority stake in a small business run by its retiring founder who says the business is in great shape. What risks do you face?

Let’s take them alphabetically…

I’ll stop there, but you get the point. Why do we do what we do again? Have a great weekend.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Stolen Bases, Qwikster, and Changing the Game

It’s Opening Day, which means it’s as good a time as ever to point out that baseball curmudgeons today bemoan the decline of the stolen base. Once one of the more exciting parts of the game with league leaders like Rickey Henderson and Vince Coleman in the 1980s swiping upwards of 100 bags per season, the league leader in 2022, Jon Berti, stole just 41.

And that’s not because players are getting slower. In fact, players today are more likely than ever to steal a base when they try. The problem is that baseball teams have decided that stealing a base isn’t worth the risk. The player attempting a steal could be tagged out and saving that out is more valuable to the prospect of winning.

But count me as a curmudgeon who likes stolen bases. Where, other than in sports, can it be so much fun to take risk? So I sit around a lot and think about changes that might bring them back. Like what if baseball increased the value of stolen bases by letting teams backfill? In other words, if a player successfully steals second, the team gets to put another runner back on first. If a player steals third, they get to load the bases. And if he steals home, which for my money is one of the most exciting events in sports, it counts for four runs, the same as a grand slam.

Yes, that changes the fundamental rules of the game, but the fundamental rules of baseball were written when players weren’t quite in such good shape and did not know about optimizing for launch angles and other details that have enabled home runs to proliferate. What if the fundamentals are supposed to be that home runs are rare and stolen bases more common.

That’s tilting at windmills stuff because change is inevitable. But all of it is to say that if you want to change the trajectory of where something is heading, you may need to radically change the rules of engagement.

For example, Netflix got its start as a DVD-by-mail business. You used the internet to pick which movies you wanted to see, but then they were sent to you in red envelopes. Over time it became faster and more convenient to stream movies directly from the internet. This is a point where Netflix could have been disrupted. Rather than invest in the technology and content rights to make that possible, it could have tried to delay the inevitable and compete by paying to overnight all of its DVDs so they would get there faster or some such.

And in fact it did do something like that by splitting the company into two businesses: Netflix, which would spend on streaming, and Qwikster, which would try to preserve the legacy business. It was a "have your cake and eat it too" moment with CEO Reed Hastings writing at the time that “streaming and DVD by mail are becoming two quite different businesses, with very different cost structures…and we need to let each grow and operate independently.”

It didn’t work. Customers hated the idea of two subscriptions (there’s an adage in business that you should never let your customer see your business model and this was Netflix going full blown open kimono) and frankly Qwikster was a melting ice cube. Play it the other way and if Netflix had stuck to its DVD by mail guns and not changed the game, ceding streaming to Amazon and others, it probably would have disappeared within 24 to 36 months.

When presented with challenges, spend time thinking about specific solutions, but if they are just bandages or attempts to delay the inevitable, probably don’t pursue them. Instead, consider ways to change the game entirely. These ideas aren’t always practical or the most cost efficient, but sometimes they are what’s needed.

As for baseball, it’s put a lot of bandages on its business model recently, including rule changes this year that include bigger bases and a pitch clock. But its popularity continues to decline and who knows what happens next. If that can happen to America’s Pastime, is any market share safe?

– By Tim Hanson