Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions delivered to your inbox.

We Risked Our Lives to Get Back to the Office

When COVID-19 shut down the world in March 2020, it brought with it a sea change in how the world thinks about work. Everything that could possibly be done remotely shifted that way abruptly. People who used to spend 40+ hours a week together no longer saw each other in person at all. And some still haven’t.

At Permanent Equity, we were back in the office together within 6 weeks. People thought we were crazy. With so many unknowns about the pandemic, why on earth would we take such a risk?

Of course, it should go without saying that coming back was optional and anyone who had concerns could work from wherever they wanted to. Heck, I came back to the office, but paranoid as I was spent months working out of the studio nee garage with the overhead door wide open to make sure there was lots of fresh air (fortunately we had a stretch of nice weather).

But the important point is that people came back because they chose to, and I think the reason for that (after some very awkward Zoom happy hours) is that we collectively came to believe that the world was undervaluing trust capital.

Trust capital is the currency of relationships. You earn it through positive experiences with others. At work, in small amounts, this takes the form of showing up on time, working hard, and doing what you said you were going to do. Larger paydays look like sharing the blame (or acclaim) for something you might have credibly blamed on (or not attributed to) a teammate.

But you can also spend trust capital, which is what you’re doing when someone thinks you are doing the wrong thing but you ask them to trust you and so they let you do it.

Another thing that’s true about trust capital is that different jobs require different amounts of it. On one end, for example, is software development. Because code is objectively transparent, if someone says she wrote good code, you can trust but verify. In other words, if you’re in charge of a software engineer, you don’t need to trust that she’s putting in the work because you’ll be able to tell if she is or isn’t by her output. Business development, though, is different. It can take years in that world for leads to become prospects and then customers, so a lot of trust is needed.

But the most important thing to recognize about trust capital is that it’s impossible to move fast without it. Because without trust, you need contracts. And contracts need lawyers. And lawyers are slow precisely because they exist to not trust one another.

A reality of what we do is that we often need to move fast without easily observable outputs, which means our job requires high trust. That’s true in and among the Permanent Equity team and also with our portfolio companies. Yet a funny thing about trust capital is that while it is depleted at roughly the same rate regardless of the medium (if you spend it on the phone, over email, or in person it has roughly the same value), it is earned at a significantly higher rate in person than anywhere else.

This is why we felt it so critical to us back in 2020 to get back to the office. We recognized that, in a remote setting, in jobs that require a great deal of trust and whose work product was not immediately verifiable, we were spending trust capital at a far greater rate than we were earning it back and feared what might happen when we tipped into a deficit. This isn’t to say that we made light of health risks or didn’t take precautions, but rather that the risk of losing trust was similarly real and significant.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Three Things About Bad Presidents

Since it was President’s Day this week I figured I might point out that based on recent polling, it seems likely that no matter what happens in the upcoming presidential election, most Americans will be unhappy with the result. I will say three things about that…

One: My former direct report Morgan Housel says that the most controversial piece he ever wrote based on reader feedback was this one. Called “The Best Presidents for the Economy,” it presented historical data about how “the stock market, corporate profits, GDP, and inflation have done under every president since Teddy Roosevelt.” While those tables have disappeared from that article, here’s the updated data on real GDP growth:

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis via Morgan Housel; *Partial term

Like Morgan did, I will simply leave that there and let you “create a story around it as you wish.”

Two: Political uncertainty in the US is being cited as a significant risk factor in 2024. Here, for example, is Time calling it the number one global risk. And here are US CEOs telling KPMG that political uncertainty is the top risk to growth. In other words, it’s safe to say that people are worried about the upcoming election and positioning accordingly.

Three: When it comes to politics, “epistemic spillovers” are a thing. What this means is that if you agree with some politically, you are more likely to take their guidance and advice on other matters even if that person has no relevant knowledge in that domain. This leads to “suboptimal information-seeking decisions and errors in judgment.” Keep that in mind and try to remain objective about non-political decisions amid heightened political rhetoric.

And those are the three things I’ll say about that. Have a great weekend.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Don’t Fix Obvious Problems

One idea that resonated more than I expected was FOMOBOMO. Mark, not that Mark, for example, emailed me back to say that thanks to FOMOBOMO, he finally could explain why he was paying down his mortgage despite having a great interest rate.

The reason that’s so is because all of us do things that don’t objectively make sense, but that make sense to us, and also that there are times when it may be optimal to do something that is clearly not optimal. This, I think, is not exactly FOMOBOMO but a corollary to it, which is the thoughtful and deliberate making of obvious mistakes (TADMOOM?).

The reason Mark paying off his mortgage is a mistake is because he’s paying 3% or so to carry it, but could earn more than 4% today on a 20-year treasury. In other words, there’s an obvious and accessible risk-free opportunity that would generate a better return.

Except!

Mark perceives non-economic benefits of being debt free, and who is anyone to tell Mark about the relative value of the perceived benefits of his household balance sheet?

You could argue, of course, that Mark is not making a mistake in this example because he believes he is deriving value in excess of cost and that’s how one makes a market anyway. But I think it’s clear here that there is no world where Mark ends up objectively better off by doing this. He just thoughtfully and deliberately wants to do it.

Somewhat related, Jason, who runs our airplane parts paperwork business out in California and has a substack where he records his own thoughts on business and operations, wrote recently about the immense relief of not fixing obvious problems.

While that sounds like gross mismanagement (we’re watching you, Jason), what it’s in recognition of is that time is finite, perfect is often the enemy of good enough, and if you’re always trying to optimize everything, you might not get around to optimizing what matters most. There is, however, a fine line here. If we’re not aiming for perfection, what are we doing? And how much imperfection can an endeavor tolerate?

Unfortunately, there’s no clear, right answer. The best you can do is hire good people and trust their judgment, but also always be positioned to be able to tolerate – deliberate or otherwise – inevitable obvious mistakes.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Great Ideas Like Great Songs

It can be entertaining when you have an old soul like Taylor (shoutout compliance!) and a gen Z soul like Holly (shoutout Vanderpump Rules!) in the same office together because you end up having some very interesting intergenerational conversations. So it went after the recent Grammys with Holly extolling the virtues of the winners while Taylor couldn’t stop harping on how music used to be so much better (though both agreed that Tracy Chapman’s performance of “Fast Car” with Luke Combs was fantastic).

To make his point, Taylor asked how many of the 2024 Record of the Year nominees besides Taylor Swift (Miley Cyrus, SZA, boygenius, Victoria Monet, Olivia Rodrigo, Billie Eilish, and Jon Batiste) would still be household names in 30 years? Whereas if you went 30 years back and looked at the same list (Whitney Houston, Neil Young, Sting, Billy Joel, and Peabo Bryson & Regina Belle) it was a veritable who’s who of staying power (though it might be stretching it to say that about that last pair).

And it does seem to be the case that the farther back you go, the more established ROTY nominees seem to be at the time they received their nomination. But is this evidence that music is getting worse?

I think the answer to that is no because the historical performance of an artist is not a reliable proxy for quality of new material (even The Beatles had “Revolution 9”). Further, it’s undoubtedly the case that digital distribution and social media together have made it exponentially easier and cheaper for unestablished artists to go direct-to-consumers and create hits solely on the merits.

Indeed, this breakdown in control of what music gets produced and distributed is likely a bigger factor in the proliferation of “unqualified” ROTY nominees than relative degradation in quality of product. (Also, Occam’s razor, Taylor might just be grumpy.)

To wit, rewind 30 years and it wasn’t like Grammys were being awarded on the merits anyway. Here, for example, were the nominees for ROTY in 1993: “Tears in Heaven” by Eric Clapton, “Achy Breaky Heart” by Billy Ray Cyrus, “Beauty and the Beast” by Celine Dion and Peabo Bryson (heckuva run for Peabo in the 1990s), “Constant Craving” by k.d. lang, and “Save the Best for Last” by Vanessa Williams. Sure, Eric Clapton and Celine Dion are juggernauts and those are good songs, but not even nominated was “Smells Like Teen Spirit” by Nirvana, arguably the best and most influential record of the past 50 years.

Yes, at the time “Achy Breaky Heart” was recognized as a superior record to “Smells Like Teen Spirit” (which won not a single Grammy in any category). We can agree that’s a miss.

The point is that great songs, like great ideas, can come from anyone anywhere at any time, and just because someone had one before doesn’t mean they will necessarily have one again. Therefore, systems should be set up to recognize and capture greatness no matter its origin. Thanks to technological advances, I think that’s what we’re increasingly seeing in the music industry and if that means more artists that haven’t had or don’t go on to have decades-long careers are being nominated for awards, that’s a feature not a bug.

It’s the same in business, with breakthroughs as likely to come from the shop floor as the C-suite. So if you own or operate one, a good question to ask is are you regularly capturing and evaluating ideas from across the entire organization?

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos gives the advice that the most senior person in a meeting should always speak last and in his recent interview with Lex Fridman advised that meetings go around in order of seniority. While I appreciate the intent of that approach (if one exec doesn’t assert undue early influence, there is more likely to be a debate on the merits), it (1) seems inefficient and procedural (shouldn’t the insight most likely to advance the conversation the farthest go first?); and (2) doesn’t solve for the fact that in a small room a group might coalesce around an idea based on who presented it regardless of when it was presented anyway.

Yet I also can’t top it because alternatives such as anonymous idea generation or trying everything and seeing what sticks come with similar problems.

One thing I will recommend, however, which I don’t think many organizations do, is an idea audit. This is the process of looking back at what you did over the past year, particularly with regards to new initiatives, and identifying who or where the idea for doing that came from. Once you have attribution, you can see whose ideas your organization is most frequently implementing.

My hypothesis when you do this is that the majority of ideas will come from a minority of origins. Then a question to ask is do one or a small number of people have a monopoly on good ideas at my organization or does my organization not have a good system in place for collecting and evaluating ideas from everywhere?

While it’s comforting to assume that the former is the case, if you agree that great ideas, like great songs, can come from anyone anywhere at any time, then what you’re seeing in that idea audit data is actually a reflection of the latter.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Why So Much Cash?

One question we get quite a bit from investors when they see our track record for making cash distributions from our funds is why do you and your companies throw off so much cash? Because with the S&P 500 yielding less than 2% and many public companies paying no dividends at all, ours look high by comparison. There are a few reasons.

First, our businesses are typically structured as pass-through entities. What this means is that they don’t pay corporate income taxes, but rather “pass-through” both tax liability and the cash to pay that tax liability to their owners. In other words, the dividends paid by our companies and funds, unlike the dividends paid by C corps, are issued on a pre-tax basis, which will make them definitionally higher.

Second, when it comes to capital allocation, there are really three things a business can do with its money:

Pay dividends.

Buy back stock.

Reinvest in the business.

For C corps, they not only pay dividends after paying income taxes, but individuals receiving them then have to pay another 15% to 20% in dividend tax. Leaving aside the issue of whether this double-taxation is fair or not, what it means for C corps is that they get more bang for their buck on behalf of their owners by either buying back stock or reinvesting (because those activities are not taxed twice and reinvestment can be tax-advantaged through policies like accelerated depreciation), so if they are being rational about value creation they will do more of that and less paying of dividends.

Third, incentives. Because we like dividends (more on that below), the people who run our businesses are typically bonused based on the amount of cash they distribute out of the business. This stands in contrast to the compensation plans of many CEOs of public companies who are rewarded based on stock price appreciation. The thing about dividends is that when they are paid out, cash (a balance sheet asset) leaves the company, so the stock price goes down (not good if your bonus depends on the stock going up). Buying back stock and reinvesting, on the other hand, are both things that give a stock price a better than 0% chance to go up. “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome” indeed, as Charlie Munger used to say.

Fourth, there’s a relationship between the size of a business and its ability to tolerate reinvestment and growth, and our experience has been that the more aggressively one tries to reinvest in and grow a small business, the more risk one introduces into its operations. Because remember that anytime you create the opportunity to make gains, you are simultaneously creating the opportunity to take losses. So while our operating team works with our companies to maintain ranked lists of reinvestment opportunities, they are typically never executing on more than one or two of them at once. That’s in order to stay focused on making the reinvestment we’re making successful, but also so that, if it isn’t, we haven’t bet the company.

Fifth, cost of capital matters. When it comes to reinvestment, our businesses are typically reinvesting in scaling assets such as vehicles, machinery, or facility expansions. Because these assets are tangible and easy for a lender with a lower cost of capital such as a bank to underwrite, it’s typically cheaper to finance them that way than with retained earnings. And so we do.

Finally, the golden rule applies. As investors, since we are the ones who have to face the consequences of any losses incurred by our investment decisions, we think we should also be the ones who get to decide what to do next with any gains – and we think our investors deserve the same courtesy. This is why distributions paid by our companies to our funds are almost entirely paid forward to the fund investors as beer money rather than recycled by us into something else. We feel that if, after receiving their cash, our investors want to give them back to us to reinvest, they can do so by committing to a future fund, but that that should be their, and not our, decision.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Puke and Clean Up

A question I’ve gotten more and more as this whatever-it-is goes on and on is: “How and how do you find time to write a daily email?” To which I reply, “Just puke and clean up.” But you may also want to know the details (besides, of course, ruthlessly feasting on prompts from others and having a fantastic editor-illustrator)…

My son’s middle school is a block from Permanent Equity’s office, and I drop him off at 7am. The two of us have a 20 minute drive into town and usually try to talk about something interesting on the way (him more and more begrudgingly). By 7:10 I am ideally parked at the office with a half-formulated thought, hashed out with a begrudging teenager, about some aspect of capital, opportunities, or people (though he wouldn’t phrase it that way).

Before I do anything else, I pull out my laptop and puke out as much of whatever that is as I can remember onto the page. Next, I go running.

Running for me is therapeutic, cathartic, and meditative, and therefore when I do my best thinking. If I’ve puked something out on the page, it’s while running that my mind considers if there is more to remember and also how to clean it up. And if I don’t stop running until I’ve remembered it all and cleaned it up, voila fini (as my friend Elsa in Switzerland says), there it’s done.

Something that’s potentially interesting about this “process,” if you want to call it that, is that it has two phases. The discovery phase, with my son, is social. It’s judgment free and about bubbling things up that others might find entertaining or interesting and getting as much of that into the world as possible. The refining phase, when I’m running, on the other hand, is antisocial. It’s about ruthlessly deleting and reworking words and ideas that 30 minutes ago held promise.

And I think that makes sense. Good ideas need both points of view and a point of view (and I think meetings should be organized in those categories as well).

Another maybe interesting aspect is that this process doesn’t yield predictable results. In fact, I try to work up to a week ahead or more in order to protect against the inevitable days when it yields nothing at all. Failure isn’t just an option or possibility, it’s an inevitability. Embrace that and protect against it.

What is predictable, however, is that I do it. Because if you want to do anything well, even creative things, my experience is that you have to approach them systematically.

In other words, puke and clean up. Regularly. Try it this long weekend. And have a great one. We’re back Tuesday.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

What We Invest In

Every now and again it’s important to revisit your value proposition to make sure (1) it’s still true and (2) you haven’t inadvertently drifted away from it. And so Brent and I did that recently with our investment approach. We wanted to clarify what it is we invest in and make sure that we remain on the same page.

Before we did that, though, we looked back at how we’ve characterized our investing approach through history.

In 2015, for example, we told the world that we “buy boring businesses.” Then in 2017 we called U.S.-based businesses valued under $50M the “greatest (legal) investment opportunity currently available.” The bar moved a little bit in 2018 when we said, “If we believe a company is staffed by a solid team, has a defensible market position, and can be bought at a fair price, we’re interested in anything above $2M in earnings.” And then we rebranded in 2023 when we said goodbye to boring businesses and look forward to working with companies that “care what happens next.”

Of course, there’s nuance to what you call something and what that something is, and so we compared the qualitative traits that made up those named opportunities. For example, here’s the CliffsNotes description of boring businesses from 2015:

Under the radar with thoughtful leadership and capable and loyal employees that are profitable and growing sustainably maintaining low levels of debt while improving the lives of their customers.

And here’s how we described a company that cares what happens next in 2023:

A business built over decades to not only deliver profits, but also employ communities with good-paying jobs and be in partnership with vendors and customers.

Different names, yes, but remarkably similar traits.

Armed with that background, we wrote down what it is we think we look for in investments:

Smaller companies with a track record of generating meaningful distributable free cash flow (i.e., beer money)

Situations where our value proposition (no debt, long time horizon, no assholes) give us an advantage in negotiating the price, terms, and structure of a deal relative to other buyers with willing sellers.

Business set-ups where there are clear opportunities for us to assist in areas where we can be helpful (hiring, technology, capital allocation/working capital management) and add value.

And when we put it that way, we concluded that our value proposition and investment approach still made sense. Onward.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

I’m Not Pissed

Someone called me the other day to tell me specifically that he wasn't pissed about something.

“I appreciate that,” I responded. “But it’s fine if you’re pissed. You’ve identified a real problem, I’m sorry that we’re not in a position to solve it yet, and I appreciate the fact that you care.”

Because that’s the thing about anger. While it is an ugly emotion, or at least can express itself in ugly ways, it doesn’t come from nowhere. Rather, it’s the result of thinking something is important and not having the world around you agree with you.

The fact is that’s going to happen from time to time, and it’s good that it does. Because the opposite of anger isn’t happiness or optimism; it’s apathy. Apathy means you don’t care enough about something to get angry, and not caring means nothing will ever get better.

What’s important if you’re angry, however, is to think long and hard about how you want to express that anger. The reason that’s so is because if the world disagrees with you, then there’s a pretty good chance that you’re wrong. (Something about efficient markets yada yada…) And if you yell at someone or sabotage something out of anger and also turn out to be wrong, well, you will have lost a lot of credibility.

That said, there’s also the chance that you’re right, but not right right now. This was the source of the anger in the above example, and a situation like that can be the most infuriating of all in the sense that there is a wrong to be righted, but not the means to do so.

So it lingers.

My experience is that these types of situations are the main reason why employees get pissed at their employers. Further, that anger is exacerbated when the reason or context why someone is not right right now is not shared.

I wrote previously that my personal policy on transparency is that I will answer any question asked of me or if I can’t or won’t, admit that and explain why. I like that policy because (1) it causes me to explain my thinking and it often becomes apparent in the course of saying or writing something if it is or is not defensible and/or (2) it usually defuses anger by acknowledging that it’s there even if it can’t be resolved.

See, at the end of the day, it’s good for everyone to get pissed, but not good for anyone to stay pissed. The reason that’s so is because getting pissed is caused by caring and having a misunderstanding of the merits while staying pissed means either the merits aren’t being shared or decisions aren’t being made on them. Long-term, those are both big problems.

The biggest problem, though, remains apathy and particularly with apathetic people being mistaken for satisfied ones for longer than anyone anywhere cares to admit.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Whole Ass or Half?

The most impressive Excel spreadsheet I’ve ever seen was built by our man Josh at Craig Frames. Prior to our involvement, with that business growing faster than it could resource, Josh essentially engineered an entire ERP in a spreadsheet, including all historical sales and pricing information, inventory positions, SKUs, you name it. Never mind that the thing took 40 minutes (really two to eight, but it felt like 40) to load, it was awesome.

As we got to know Josh better, we understood why he did that. It’s because no matter the situation, he’s “whole ass.” What’s “whole ass” besides a delightful turn of phrase? The opposite of “half ass,” of course, which is how Josh never does anything.

That said, while it may sound ideal to be whole ass all the time, the approach can be counterproductive. Josh realized this when he found out his daughter (also whole ass on everything because she’s been indoctrinated by dad) was trying to play soccer on a broken toe (still led her team in scoring, but in hindsight perhaps not worth the risk). And we’re working to replace the whole ass spreadsheet with something that doesn’t take quite so long to load.

So if doing too much doesn’t reliably work, what about just doing less? This is half-assing it, and it doesn’t work either. And that’s despite the fact that I’m a big believer in the Pareto principle, which says that you can expect 20% of your effort to drive 80% of results (I’d even posit the real ratio is 90/10, which is to say that you can accomplish a lot by doing little).

But the reason you can’t just do the 10% is because it can be very difficult to understand in real time or even in hindsight which 10% is/was the 10%, which is as frustrating and unsatisfying as it is inefficient.

This leads me to my point, which is that effort, and particularly incremental effort, is incredibly overvalued. But, and it’s a big but, if you don’t put it in, your value can quickly go to zero. To square that circle, I think it means trying to direct more effort into things you don’t know well while reducing effort on things you do, all the while maintaining consistent sum total effort.

In other words, try hard always but always on different things. By doing that, perhaps you’re whole ass and half.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Can Main Street Innovate?

It feels good when people ask for your opinion on something, so it made my morning the other day when I had a notification on X nee Twitter from one Chris Unsworth. His question?

“Is Google’s 20% time idea applicable to Main Street business?”

What he’s referring to is the policy (perhaps apocryphal, though promoted at the time of the company’s IPO) that full-time Googlers are supposed to spend 80% of their time on the clock doing what they were hired to do and the other 20% on something of their choosing that they view as innovative or high potential. This allegedly led to the creation of Gmail as well as AdSense and Google News and made the company a desirable place to work.

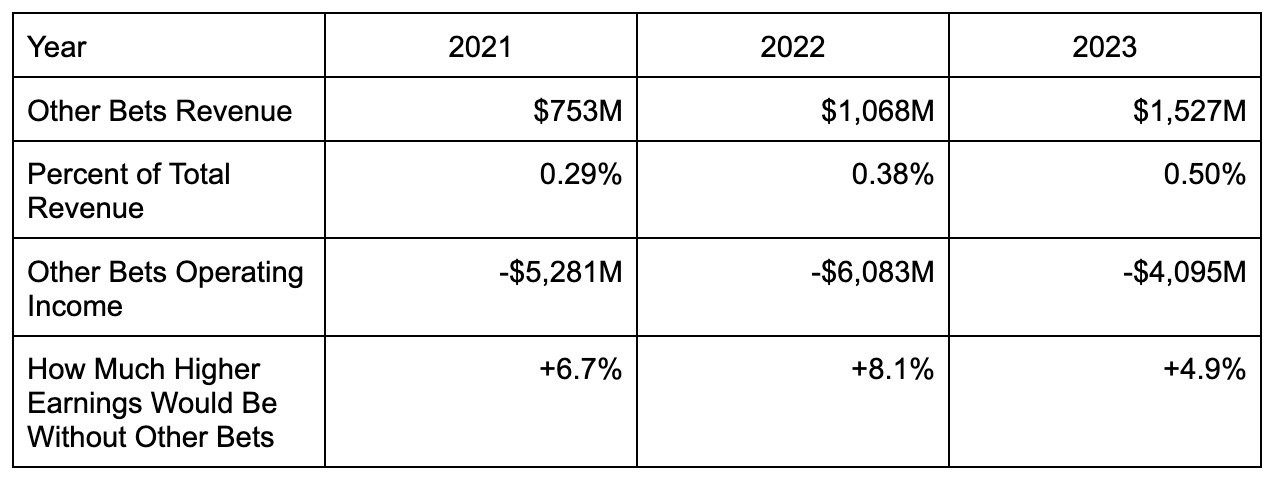

This, however, is an undoubtedly expensive policy for Google to maintain with uncertain return potential. And while Google’s parent company Alphabet doesn’t provide the world’s most transparent financials to investors, you can see in recent results that its “Other Bets” segment (where one might expect these novel ideas to be housed as they are commercialized) is contributing little to the company’s top line while being a significant drag on profits.

Further, you can see that under pressure to be more profitable last year, this is one area where Alphabet opted to cut costs.

The argument for spending 20% of your day on unprofitable, non-core stuff, however, can be summed up in the widely-held business aphorism that if you’re not growing, you’re dying. The world, after all, is cutthroat competitive and if you’re not getting better all the time (and not just incrementally better) someone else will drink your milkshake.

At this point, it’s probably worth unpacking what a “Main Street business” is. This is one that’s relatively small, a community employer but without access to A+ talent, probably geographically constrained, profitable but a few bad months from being not, and private. There are tens of millions of businesses like this across the US that employ some 20% of workers. And the question is “Can these businesses afford to let workers spend 20% of their time on unprofitable, non-core (albeit innovative and high potential) stuff?”

The answer is probably not. Bankruptcy filings in this segment were up more than 250% in 2023, with a main driver being higher financing costs eroding already thin profit margins (and that’s if many of these businesses could get their customers to pay them). This leaves little money left over to invest in innovation that might eat up 5% to 10% of the bottom line, leaving aside (and apologies if this sounds patronizing) the fact of whether small business operators can even trust their employees to know how to spend that time.

But they also have to do something. Consolidation is a real trend, and if you’re only playing defense in anything, you will eventually lose. It’s just a question of how long it will take to meet your end.

So how might Main Street businesses innovate and remain solvent? That’d be a good topic for a panel at Main Street Summit later this year, but one answer is to make only targeted bets. Keep a list of everything your business might do to grow or innovate, but force rank them based on return potential and difficulty of implementation and only tackle one or two at a time having established a finite budget and clear milestones to track progress. Another is to watch competitors and industry peers like a hawk and be shameless about trying things they are doing that might be working (effectively letting them finance your innovation for you). Or go public and let outside investors finance billions of dollars in losses for you.

But that last one is probably not realistic. For the time being, at least.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Dignity on the Magic Flying Train

It was my son’s 13th birthday recently and he asked to visit the (relatively) new aquarium in St. Louis. That seemed reasonable, so I said sure and took the family.

When we got there, it was apparent that this was more of an entertainment venue than a scientific endeavor. And while my son would have been more excited about the latter, there were still fish to be seen, so we pressed on.

Before we could enter the aquarium, however, we were compelled by a very energetic “conductor” to take the train ride. Of course, this just wasn’t any train ride, it was a magic flying train ride, and it required the passengers to help provide the magic to get it going. So the very energetic “conductor” asked if it was anybody’s birthday.

While my surly and cool children and I could see what was coming next from a mile away, my very lovely wife either (1) could not or (2) could, but didn’t care because she shot up her hand, pointed at our son, and yelled delightfully “It’s his birthday!”

My son was bewildered. But it gets worse…

The “conductor” told him that birthday magic was the most powerful magic of all and so for the magic flying train to get off the ground, it would require him to yell “Choo choo!” as loud as he could.

If he was previously bewildered, now he was mortified.

But all of the little, younger kids on the train whose birthday it wasn’t and who wanted to ride the magic flying train to the aquarium stared at him expectantly.

“Choo choo,” he choked out.

“You can do better than that!” exclaimed the “conductor,” not reading the room but also reading the room.

“Choo choo,” he said again a little louder.

“Good enough,” she replied, and the magic flying train took flight.

Thankfully, if there are any lasting effects from this trauma, they haven’t materialized, and now my kids have a code word (choo choo) they can use when they think my wife and/or I are embarrassing them.

As for why I’m telling that story in this space, reader Nate asked for more demolition videos during season 3, and while I don’t have the footage, I’d put the narrative description of my wife demolishing my son’s dignity in that genre.

Have a great weekend, and choo choo.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Entertaining and Likable

Emily and I spoke to some business school students the other day and after 55 minutes of good questions about deal flow, position sizing, valuation, and the like, the professor said, “With five minutes left, what else should they know?”

Emily turned to me and said, “Tell them why you took a job at a small firm in Columbia, MO.”

It was an interesting prompt, and I didn’t immediately know where to take it. I also have a habit of when I don’t know the answer to something, talking my way around it until I figure it out. So I jumped into my usual spiel about having worked in public equities with my last job there leading a team of software developers and data scientists to ingest research from about 100 equity analysts working around the world to try to figure out who was lucky and who was good and for those who were good, what they were good at and how analytics might make them better. My conclusion from that work was that we are all luckier than we think and that the opportunity for edge in the public markets was being eroded by technology.

But Permanent Equity was different.

Unlike in public markets, where every investor sees the same companies and the same prices at the same time (acknowledging, but intentionally omitting, high-frequency traders), Permanent Equity could (1) cultivate proprietary deal flow; (2) negotiate both price and terms; and (3) seek to add value post-close. That’s way more levers available to the typical public markets investor, and that was both interesting to me and different.

And when I said the word “different,” I realized that was the answer.

A key to success, I said, is to do something that is genuinely different. When I encountered Permanent Equity, I gauged it to be genuinely different in its model and approach. That was exciting to me.

But if you want to build a career in anything, not only should you work somewhere that is doing something different, you need to be genuinely different as well. One form this can take in finance is by being a good writer. It’s conventional wisdom that you need to be at least reasonable with numbers in order to buy and sell things for a living, but it’s one thing to calculate a return profile and another to persuade someone to take the risk of earning it.

Another differentiator is to be entertaining and likable. That’s because doing a financial job well is about building and maintaining relationships more than any quant would care to admit.

After all, the thing financial people won’t tell you about financial math is that it’s learnable and not as hard as it looks. What’s harder is keeping relationships. And that’s exactly what they (you?) should know.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Systems Scale

The two things most sent to me over the holidays to listen to were (1) Lex Fridman’s interview with Jeff Bezos and (2) Patrick O’Shaughnessy’s interview with Justin Ishbia. And because I take seriously the benefit of having other people curate the internet on my behalf, I have since listened to both more than a number of times.

Hearing these successful entrepreneurs speak at length about their professional journeys has facilitated at least one epiphany for me. Namely, that you need more systems to scale than you think you do, but also that sustaining working systems is harder than it looks. For example, here’s Ishbia, perhaps the most systems-driven investor I’ve ever encountered, putting it bluntly: “To create enterprise value is a system…and the system for us is documentation.”

Then he went on to rattle off any number of specific systems that govern their investment process at Shore Capital: the nine innings of idea generation, the four quarters of closing a deal, the 100 day plan, the 23 standard operating procedures, see one/do one/teach one, the basketball team board, etc.

“We do the same thing every time,” he said, which is obvious by how quickly he can describe what they do, and what he promises his investors is not an outcome, but a process. This, I think, is the only way to do, as Shore did, 586 deals over the past three years (for context, Permanent Equity did seven). Indeed, it’s incredible what Ishbia and his team have built. The only way to scale is through structure (even in creative endeavors), and I wish I and we were a tenth as systematized as he and Shore seem to be.

Yet here’s Bezos speaking on what it means to embrace Day One thinking:

Day One thinking is we start fresh every day and we get to make new decisions every day…When we work on programs at Amazon, we often make a list of tenets…the main ideas that we want this program to embody…but we put in parentheses “Unless you know a better way.”...That idea…is so important because you never want to get trapped by dogma. You never want to get trapped by history. That doesn’t mean you discard history or ignore it. There is so much value in what has worked in the past, but you can’t be blindly following what you’ve done.

To support this notion, Bezos talked about having a “skeptical view of proxies”:

One of the things that happens in business is that you develop certain things that you’re managing to…like a metric. What happens is that inertia sets in. Somebody a long time ago invented that metric…they had a reason why they chose that metric. Then fast forward five years. The metric is a proxy for truth…but you forget the truth behind why you were watching that metric in the first place and the world shifts a little…You have to be on alert for that. It is common in large companies that they are managing to metrics they don’t really understand, they don’t really know why they exist, and the world may have shifted out from under them a little.

When Patrick asked Justin about Shore’s returns, he alluded to 50% to 70% IRRs, which are incredible. Later Ishbia talked about his investment strategies as products with the system of going from thesis to platform to add-ons to exit working in part because it is an assembly line. What Shore is doing is building a product over time (in this case an investable business as an SKU) that will go from being unbuyable by strategic or institutional capital to being not only buyable, but also re-sellable, which is a hugely valuable trait to the Shore Capital customer.

That’s interesting because in order to back into 50% to 70% IRRs over five years if you are buying at, as Ishbia described in, 7.5x EBITDA with 2x leverage, you need something like 400% earnings growth and multiple expansion to 15x or some similar combination. So a question I would have is where are the returns coming from and how might they be impacted in a world of multiple contraction due to higher interest rates? If they are slashed, would it make sense to rethink the system to accommodate longer hold periods?

The answer, of course, is maybe, but maybe not (but I think maybe since the value of that SKU will fall when buyers have less purchasing power). But who knows. So do things systematically, but always skeptically, because the world never stops shifting and there may be a better way…for now.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

The World’s Best Cup Of Coffee

We continue to up our coffee game here at the most caffeinated private equity firm in America, and most recently that included, under Taylor’s watchful eye, the acquisition of a Eureka Mignon grinder, Ratio brewer, and Acaia digital scale to ensure that we are always preparing precisely the right amount of beans precisely. So expectations were high when we brewed our first batch…

The verdict? Something seemed off. We revisited all of our assumptions one by one and then hit on the culprit. The water. The water didn’t taste great.

When it comes to achieving success at anything, there are really three paradigms that describe what might work:

You’re only as strong as your weakest link, i.e., the best you can do is your worst input.

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts, i.e., your inputs are all better together.

Go big or go home, i.e., your best input is your biggest driver.

Making good coffee is clearly an example of paradigm 1. We could have the best beans, grinder, and brewer in the world, but if our water is bad, our coffee will be too. In other words, we can’t organize our brewing process differently or invest in an even better brewer in order to fix our water problem.

Thankfully, one benefit of living out in the country is that I have a really deep well. So in pursuit of a better cup of coffee, I started commuting in every morning with a jug of sustainably sourced spring water from a limestone aquifer. And that did the trick. Now, not only do we now have the world’s best cup of coffee, but since I also drive an EV, our coffee’s ESG rating is off the charts.

The point is if you’re trying to do something and it’s not succeeding like you’d like it to, you need to take stock of the situation to figure out which success paradigm applies. To achieve greatness, do you need to make your best better, put your parts together better, or raise up a laggard? Once you know that, it’s much easier to target effort and investment to achieve the highest return.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Strategy and Execution

Here’s a thought experiment for you…

Let’s say you have two companies of similar sizes with similar needs that want to create value. In thinking through how to do that, you decide to focus on the following:

Grow the balance sheet to take on larger opportunities.

Hire to open new markets and broaden geographic reach.

Invest to bring capabilities in-house in order to vertically integrate and capture more of the value chain.

Is this good or bad strategy?

The answer is, and I know this is the answer because we happened to run this A/B test at Permanent Equity, it depends. Because we did these three things at two of our similar-sized businesses and while one more than doubled sales and profits over 18 months, the other increased sales, but swung to losses. The reason that’s so is because growth is risk, and if you don’t execute amid increasing complexity and scale, those things will eat you alive.

So whether or not something is good or bad strategy depends entirely on execution.

Our good friend Scott Felsenthal, who runs a fifth generation family business, posted this on X recently: “Anyone can copy strategy, but not execution. The point is…do what you do better than anyone else. It’s completely within your control.”

To which I responded: “A corollary is that strategy without execution is hokum.”

What’s interesting is that I think you can execute your way out of bad strategy, but you can’t strategize your way out of poor execution. That’s interesting because “strategic” jobs tend to be higher up, higher paid, and higher profile while execution is on the front lines and taken for granted. This is why Undercover Boss is such a compelling premise. It forces higher-ups back onto the front lines and they inevitably learn something about execution that then helps inform strategy.

So just as if you operate a business you should constantly be talking to your customers, you should also regularly be on the front lines executing. If you’re not, hokum.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

What You Think You Do

I remember the first time I sat in on a customer interview. I’d spent my career to date publishing research for individual investors under the assumption that they wanted help identifying stocks they didn’t know about that were likely to go up, but here I was trying to help the Product team figure out why the people who paid to get that research weren’t actually buying the stocks.

The woman leading the interview asked a series of questions and over the course of the conversation it became clear that the customer wasn’t interested in my stock ideas, but rather if I thought his stock ideas were any good. See, it wasn’t discovery he was after, but validation. Where the customer found value was in knowing if a professional thought he should buy stocks he already wanted to buy.

At that moment I realized that we didn’t sell information, but confidence, and my mind was blown.

Leaving aside the specific implications of that epiphany for that business model, the broader point is that if you operate a business and you’re not regularly talking to your customers, there can be a material difference between what you think you do for them and what you actually do for them. And if there is, that’s a massive barrier to growth because you will never double down on the value proposition that’s making your business go.

We see this all the time in the Permanent Equity portfolio of companies. For example, when we invested in our airplane parts business, we thought it sold airplane parts. But we realized along the way that while lots of airplane parts businesses sell airplane parts, far fewer could reliably and quickly trace those parts to their origins. This trace is a requirement for airplane parts to be installed on commercial aircraft, and that can be a problem for a customer who needs to find a useful part quickly. And while existing customers knew our airplane parts business could do this well, potential customers had no idea.

So the management team at the business worked to digitize their trace documentation and put it online. Now customers can see immediately that our business not only has the part in question, but crucially that they can use it to solve their problem.

Sales are up.

Because what we learned in talking to customers is that they aren’t in the market for airplane parts, but for reliably useful airplane parts. The joke now is that our airplane parts business isn’t in the airplane parts business at all, but in the business of digitizing paperwork. Though to paraphrase Shakespeare, there is truth in every jest.

Have a great weekend.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Expectations are Hard

Say what you will about social media, but it has its days. One of these, for example, was December 4, 2023, when @ajb_powell reposted what he called the “GOAT [greatest of all time] 2020-1 bubble thread.”

That post (though it would have been a tweet back then) was from @BrianFeroldi. He had asked the world way back in 2021 to name a company that was worth less than $10B then but would be worth $500B or more in a few decades. Having received 710 answers, he proceeded to list “20 top stocks that have 50x+ potential.”

Acknowledging that it’s only been 2.5 years and not a few decades, the results are still, well, not good. Not a single one of the stocks listed has gone up since then, and the average return is negative 76%. In other words, if you’d invested $100 in this basket of stocks, it’d be worth $24 today. Incredibly, the best return of the group is -31%, and the aggregate market value of the 20 stocks declined from $133B to $36B. For context, the market is up 15% at the same time these companies destroyed almost $100B of value.

This isn’t to take a shot at Brian. He’s a friend and these were crowdsourced ideas. Rather, it’s just to show (1) what an incredibly speculative fervor the world was in not so long ago and (2) how difficult it is for companies to meet the high expectations that get attached to high valuations.

Responding to @ajb_powell’s post, @TheStalwart said that it reminded him of the book 100 Best Internet Stocks to Own by Greg Kyle. And I thought the same thing!

A classic, published at the height of the dot-com bubble in 2000, 100 Best Internet Stocks to Own sought to identify (shocker) the 100 best internet stocks for investors to own. And 15 years ago, when I worked in public markets, my colleague Brian Richards and I decided to look back and see how those stocks had performed. I won’t bury the lede:

Had you invested $1,000 in each of Kyle’s 100 Internet names back on April 20, 2000, and held them through September 2007, your $100,000 investment would have turned into…$37,814. That’s a total return of negative 62%...You were more likely to pick a company that would go bankrupt (18) than you were to pick a company that simply increased in price (13)!

The lesson is that the more you pay for something, the more above average it has to be to pay off, but that most things (by definition) aren’t sustainably better than average. Of course, pockets of people forget that every few years and that is what it is and will be.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

FOMOBOMO

Three things happened around the same time that got me thinking…

2x international best-selling author Morgan Housel posted that, “The most important financial skill is having no FOMO.”

The 100 Best Barbecue Restaurants in America author Johnny sent me this old George Carlin bit about how anyone who drives slower than you is an idiot, but anyone who drives faster is a maniac.

Holly (shoutout Gen Z!) sent me this TikTok (because who else would?) about oddly-specific, but hilarious, financial acronyms.

And what those three things together got me thinking was that actually it’s okay to have FOMO and that that phenomenon needed an oddly specific acronym. So without further ado I present FOMOBOMO (Fear of Missing Out but Okay Missing Out)...

FOMO is the dreaded feeling that everyone other than you is doing something and finding success as a result. In its worst form, it ends up being an emotional driver of bad decisions, particularly when it comes to financial ones. In recent times, for example, you can blame the booms and busts in everything from tech stocks to housing to NFTs on FOMO, and that would be fair. But if you believe that markets are mostly efficient, it’s also true that having no FOMO at all would be stupid.

Take the Carlin bit, for example. The person he’s mocking is a person with no FOMO: the faster driver is a maniac and the slower one an idiot, implying that the protagonist is 100% happy in her own shoes. Yet if you’re on the interstate trying to make good time without getting a ticket, the faster driver is the one you want to tuck in behind while the slower one maybe knows something you don’t. In other words, the speed you’re driving is clearly not the optimal one.

Now, that being said, it could be the case that driving faster might be too dangerous for you or that slowing down won’t get you where you need to go on time. And in both of those cases it means that you’ve recognized that what you are doing is different from what others are doing, that it is likely not correct, but that you’re okay with being wrong because of your unique circumstances.

That’s FOMOBOMO. Now let’s apply the concept to the financial world...

One of the more heartening things I read recently was that “More Americans Than Ever Own Stocks.” Is it a coincidence that that’s the case at a time when the stock market is at an all-time high? Of course not! Why? FOMO.

Now, is it the case that many of these new investors will lose money in the near term when stocks inevitably correct? Yes. But is it also the case that these new investors will be better off in the long run by owning equities? Also yes. And it’s FOMO that started them on this path. Here’s the experience of one 20-something Nick Luczak:

[During the pandemic] Luczak and his fraternity brothers started a group chat to discuss markets and stock picks. He said he made a profit investing in Amazon.com and watched his friends make, then lose, thousands of dollars trading meme stocks such as GameStop and AMC Entertainment Holdings. At one point, he considered becoming a day trader.

Now, Luczak, 24 years old, is focused on long-term investing. A salesman in Dallas, he is studying to become a certified financial planner.

See, in a mostly efficient world, FOMO is what opens our eyes to opportunities we might be missing, and we all have to start somewhere. So have it. And have a lot of it!

But it’s also true that even in a mostly efficient world not all opportunities are appropriate or appropriate for you. So don’t dismiss anything out of hand, but also if after carefully considering someone else’s idea and deciding it’s not appropriate or appropriate for you (even if a lot of someone-elses have the same idea), resolve to not let their outcomes convince you otherwise.

That, to put an oddly-specific acronym on it, is FOMOBOMO.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Fun with Asymmetric Bets

I had an aha moment recently when I read about the Arizona Public Safety Personnel Retirement System Trust’s 2021 investment in English football team Ipswich Town. Because whereas I used to think buying a sports team was something ultra wealthy people did to demonstrate status and entertain themselves, I am increasingly coming around to the idea that sports teams are a fascinating asset class. So I read with great interest how CIO Mark Steed had the idea of “hedging against stock markets by buying a sports team.”

Per The Wall Street Journal, what he ended up doing was paying $30M to buy a third tier soccer team, courting its biggest fan Ed Sheeran to cheerlead the deal, and then hiring in managerial and playing talent. Now, Ipswich Town is on the verge of winning its way back into the Premier League (teams that finish first or second in the Championship division are rewarded with automatic promotion), which would make Ipswich Town worth many, many multiples more than what Arizona PSPRST paid for it.

As I thought about this investment, the brilliance of it is what an asymmetric bet it was even if it may not obviously look like one. Because here’s the Journal repeating the commonly-held view of what it’s like to own a professional football team: “By all rights, the erratic, cutthroat world of English soccer shouldn’t make for safe investing–just ask any of the dozens of billionaires who has set hundreds of millions of dollars on fire trying to keep their teams in the Premier League.”

A key difference here is that Ipswich Town wasn’t in the Premier League, but because of English soccer’s promotion and relegation system, it could be. What this means is that if you own any lower tier team, you basically have a deep, out-of-the-money call option on owning a Premier League team, but also one that should never expire worthless because it has no expiration date. In other words, a lower tier team (provided you avoid relegation) might always be worth what you paid for it because it always has the chance to be worth many, many multiples more (provided you achieve promotion).

Mathematically, that makes this a good bet. But what makes it even better is the fact that it’s uncorrelated, i.e., the drivers of the performance of the bet have no ties to the performance of the other bets in Arizona PSPRST’s portfolio. That’s because, presumably, the players should play the same regardless of whether interest rates or the stock market or the prices of molybdenum or feeder cattle or whatever are up or down.

Plus, you know, it’s probably fun to own a football team.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

I’m Co-President

One of the great recurring bits on The Office was Dwight consistently promoting himself to Assistant Regional Manager with others then correcting him that what he actually was was Assistant to the Regional Manager. It got me every time. And now I’m living it, but kind of in reverse.

See, a little more than a year ago, Brent promoted Mark and I to be Co-Presidents of Permanent Equity. And now when I get introduced to someone as the President of Permanent Equity, I correct them: Co-President, I point out.

That’s not to be a stickler, but rather because my experience is that it’s far better to be Co-President than it would be to be President, and I think it’s helpful for people to know that. I thought about this after our friend Michael asked for an update, one year in, on how the Co-President thing was working out.

I can’t speak for Mark, but my view is that it’s working out great. One selfish reason is that being President alone would require me to lead and make decisions in areas that I (1) am not good at and (2) don’t enjoy. For example, we had to think through, find, renovate, and fill new office space this past year and then figure out how people at the firm might best stay connected despite being in different locations. None of that is in my sweet spot, but it all had to be done, and done well, in order to facilitate the further growth of the firm. Mark and his team nailed it, and Permanent Equity is better off as a result.

The flip side of that is that being Co-President enables me to better lead and make decisions in areas where I am good and that I enjoy. For example, content. Thanks to Brent, Mark, Emily, Sarah, David, Taylor, and everyone else who contributed to everything we published last year, I think 2023 was one of our best content years ever in terms of quality, quantity, and regularity (and compliance). And I think I was helpful to that end (though Emily might be shaking her head).

One thing Michael also wanted to know was what Brent gets up to now that Mark and I are handling the President-y stuff. Well, he gave that update in his recent annual letter:

As CEO, my days are now primarily spent at the intersection of what I love to do and where I’ve been given talents. I get to serve our team and continue to build our culture, recruit new team members, sift potential investors and partners, architect deal structures, advise on impactful operating situations, occasionally rescue a deal, and figure out what comes next. I’ve never been more excited to go to work!

A lot of people know that I was hired into Permanent Equity as CFO. It was a role I was happy to fill in order to join the organization, but it came with a lot of responsibilities that weren’t in my sweet spot either (my sweet spot is not very big). I did my best to do them and do them well, but both I and the firm realized over time that we’d all be better off if those things were done by a person for whom they were in their sweet spot. And now we have Nikki.

Successful leadership is not about collecting titles or responsibilities, but instead about shedding them over time. I know Brent’s goal, for example, is to get to a place where he is always useful, but never necessary. To do that, one needs to be self-aware, willing to share, and able to recognize when you will hurt, not help.

We’re all works-in-progress in that regard, but one way Mark and I try to stay connected to that end is by going on a weekly walk where we run through everything that’s happening in our areas and try to get the other’s thoughts. What that ends up being (besides good exercise) is the two of us verbally processing challenges we have. What it never ends up being is one of us telling the other what to do. Most often those discussions end with something like, “I think you’re thinking about it the right way, and I trust that whatever you decide to do in your zone will be best.”

In other words, I hope I am always Co-President of Permanent Equity. Not only does that role let me lead and make decisions in the areas that are in my (small) sweet spot, but it also means that we have someone Brent and I trust implicitly leading and making decisions in the many areas that are not.

-Tim